The Chinese may have been late to join the cloud-computing revolution, but they are making up for lost time as the sector experiences ferociously fast growth.

It is being driven by the rapid uptake of the internet among consumers and the drive towards digitisation by business and industry.

The number of internet users in China last year topped 731 million people, the largest in the world and almost three times that of the United States, according to the China Internet Information Centre.

If that sounds impressive, it should be noted that only about half of the population is online, way behind the 80 to 90 per cent penetration typical in the West and highlighting the potential for future growth.

Chinese market

Just like their western counterparts, Chinese businesses and public sector bodies are turning to cloud computing because of the flexibility, efficiency and cost-savings it offers.

However, the rest of the world has not stood still either. In the Asia Cloud Computing Association’s Cloud Readiness Index 2016, which assesses factors such as broadband quality, physical infrastructure and international connectivity, China has slipped from 11th to 13th place.

The need to keep up is not lost on Beijing which made cloud computing a key part of its five-year plan for 2016-2020 and two years ago launched its Internet Plus policy to accelerate the adoption of the cloud, mobile internet and the internet of things to boost economic growth and global competitiveness.

Management consultants Bain & Company have estimated that China’s cloud market will be worth $20 billion by the end of the decade, up from $1.5 billion four years ago, and equivalent to a compound growth rate of about 40 per cent.

Challenges and opportunities

It is hardly surprising that Western technology and software companies are drooling at the prospects of breaking into or expanding in the Chinese cloud sector. They only need look at cars or fashion brands to see how lucrative China can be.

Professor Feng Li, chair of information management at Cass Business School in London, predicts growth will be “astronomical” and says: “China only began using the cloud a few years ago and the size of the market is tiny compared to America at the moment, but it is developing extremely fast and is likely to catch up very quickly.

“In the last few years foreign companies have been trying to get into the Chinese market. Their market share is still relatively small, but the potential is definitely there because of their technological capabilities, their reputation and their experience in this space.”

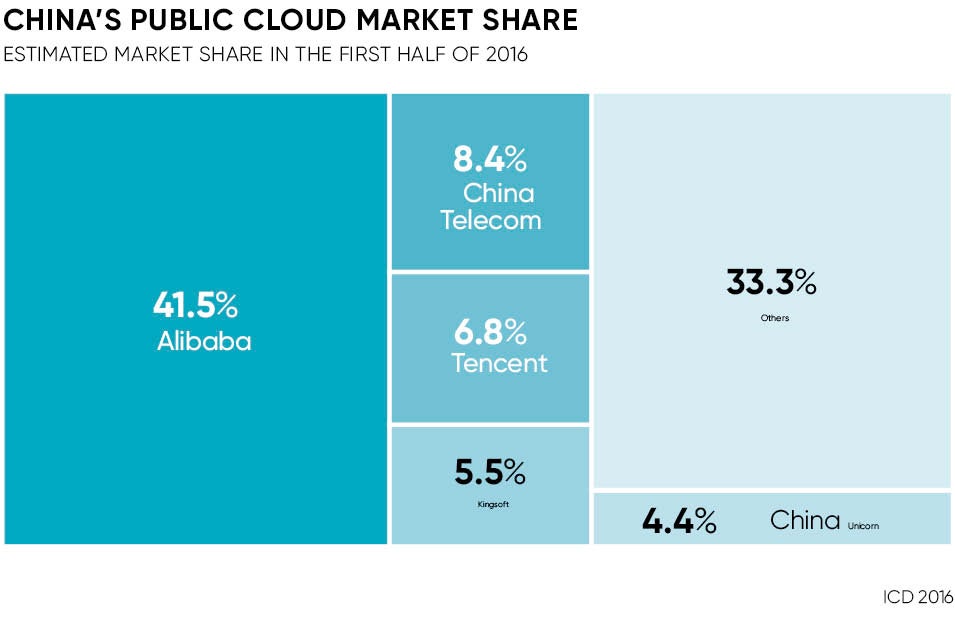

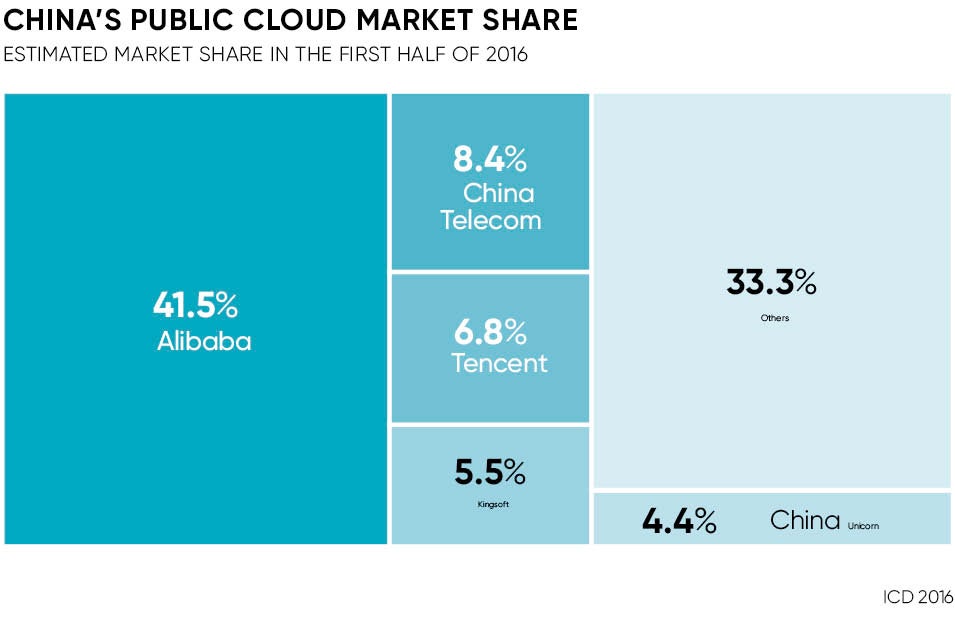

The country’s largest cloud provider is Alibaba Cloud, part of Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba, and among its many domestic rivals are search engine Baidu, social networking group Tencent and telecoms equipment supplier Huawei.

Western companies are gradually muscling in, including Amazon Web Services, Microsoft’s Azure, IBM and Oracle, but China is not an easy market to crack, as Google and Facebook have discovered, and there are big challenges to overcome for any new entrant.

The lack of internet penetration and poor broadband networks outside the big cities are major hurdles, but there is also a battery of complex regulations and legal issues to be tackled, as well as concerns about the protection of intellectual property and censorship of web content.

The digital arena has specific challenges sprouting from new national cyber-security laws announced last year which threaten tough punishments for companies that breach regulations.

Companies also face strict rules on the transfer of data in and out of China, and the use of foreign software and hardware by government bodies and state-owned enterprises.

For the UK’s fast-growing and energetic cloud sector there are opportunities to piggy-back on the likes of Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and Alibaba

Lillian Pang, vice president and associate general counsel for Rackspace, a US-based managed cloud provider with data centres in Hong Kong, says the scope of legislation is a clear indication that mainland China recognises the value and potential of its cloud market.

She warns that laws in the region are “vast and constantly changing” and adds: “Cloud providers and other organisations will need to ensure they have suitable protocols in place to comply with the various legislations.”

Another potential obstacle is that cloud providers must have a local partner, while customers who want to use their services must have a Chinese account separate from their international accounts.

As a result, Amazon has teamed up with Beijing Sinnet, Microsoft and IBM with 21Vianet, and Oracle with Tencent.

Having a local partner potentially raises concerns about how much influence the Chinese will have, but Professor Li advises foreign companies to forge close local connections, saying it is important not to underestimate cultural differences between the West and China and also within different regions of China.

China too recognises the value of international expertise and Alibaba Cloud last August unveiled is AliLaunch programme to encourage foreign companies to use its services in China and develop a cloud-computing ecosystem. Early partners include SAP, Here, Hitachi Data Systems and Check Point.

Now ranked fifth largest cloud infrastructure provider in the world, according to research firm Canalys, China’s global ambitions recently saw it announce plans for new data centres in the Middle East, Europe and Japan.

For the UK’s fast-growing and energetic cloud sector there are opportunities to piggy-back on the likes of Amazon Web Services, Microsoft and Alibaba, and although the short-term prize might be securing business in China, the longer-term gain could be more international as Chinese companies broaden their horizons.

Alex Hilton, chief executive at the UK’s Cloud Industry Forum, says the issues facing China are similar to those that face the UK such as bandwidth, security, migration from legacy systems, regulation and data sovereignty.

There are potentially huge opportunities for those that can help private and public sector clients overcome those problems and harness the power of the cloud to transform their operations.

Mr Hilton adds: “When we talked about cloud technology a few years ago, it was all about infrastructure and computing power, now it’s about the applications and software element of it that organisations can utilise. Software is king, absolutely.”

The advantage many UK companies have is they have built up expertise and experience in specialist areas, such as disaster recovery, the internet of things and unified communications that will be of immense interest to the Chinese.

Chinese market