“Go west young man” is a phrase used to describe America’s expansion westward, relating to the 19th-century concept of manifest destiny. A belief that settlers were destined to move across the continent, civilise it and remake the Wild West based on the virtues of the American people and their institutions.

Fast forward to the 21st century and there are parallels with the expansion of e-commerce out of the United States and the West. Yet the West’s taming of emerging markets in the East and South, emboldened by venture capital, a rulebook based on PLU (people like us) and a modern-day belief in manifest destiny is being met with resistance.

Some 170 years ago, this attitude fuelled Western settlement. Today Google, eBay, Facebook and a myriad of others increasingly realise they must radically localise, become customer-centric and adapt to new markets from India to Brazil, not subjugate them.

Take Amazon. Despite entering China in 2011, it still only had 1.3 per cent of the country’s online retail market last year. In Mexico, the online retailer struggled as only 20 per cent of citizens have credit cards.

“Treating international expansion from your own market perspective or making assumptions towards customers’ expectations can ultimately lead to a wrong footing and can damage your brand’s local perception,” explains Perrine Masset, regional director at LiveArea, The PFS Agency.

“In the West, we progressively learnt e-commerce, breaking down our fears slowly with more secure payments and better data security. We started with desktop browsing, migrated to tablets and now mobile.”

The UK-US-European e-commerce businesses model also hinges on a cashless online transaction mediated through a bank. This is still in stark contrast to many emerging markets. A recent PwC study found that 42 per cent of the global adult population is absent from the financial system.

“We also get excited about the middle classes because we can relate to their spending power, desire for premiumisation and general consumerism,” says Nick Cooper, executive director at Landor Associates.

“The notion that massive latent consumer demand is locked up in billions of non-property-owning, unbanked low earners using smartphones is something that Western companies cannot easily get their heads around.”

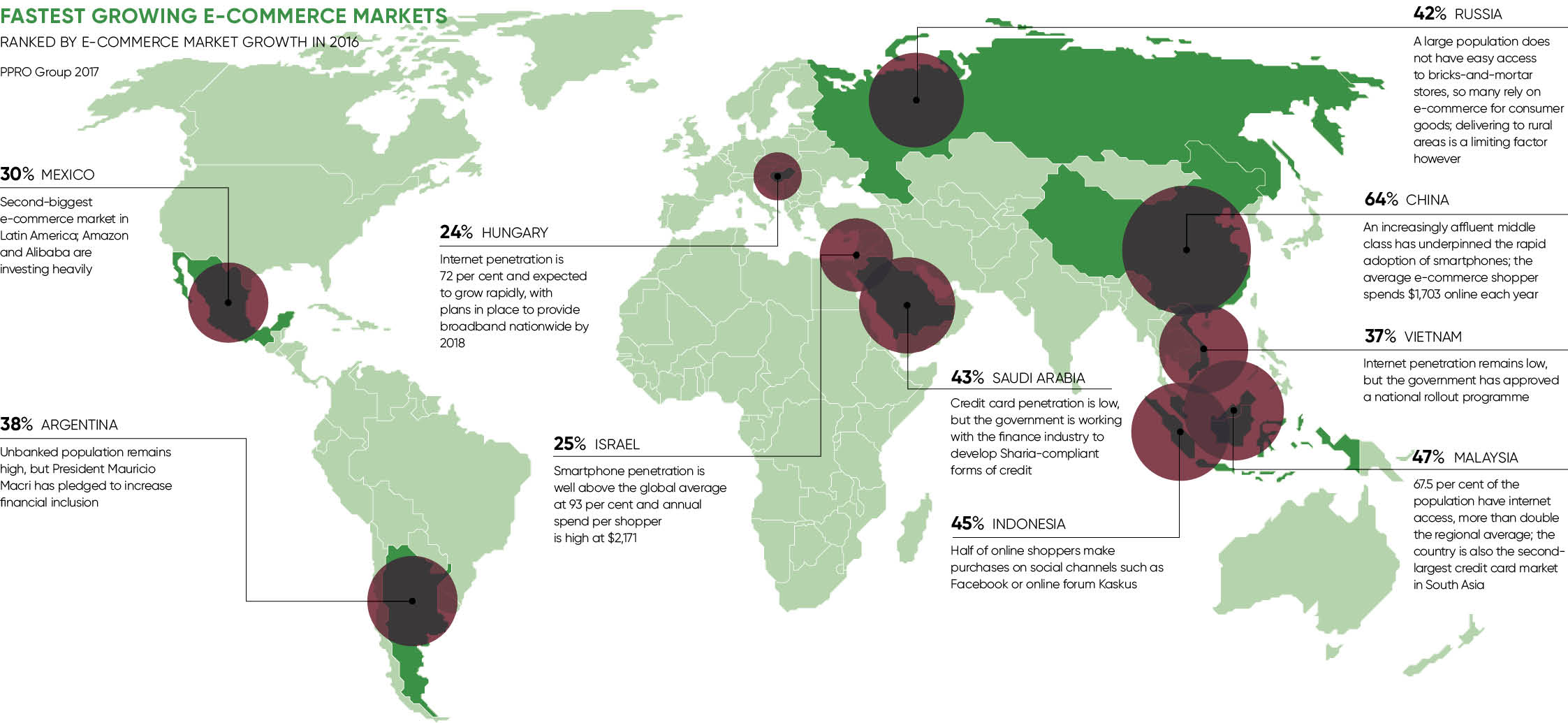

Yet stakes are high when it comes to expansion east and south. Already 450 million people in China can use their phone as a digital wallet and these services were accessed more than a billion times last year. India now gains three new internet users every second, according to Morgan Stanley, while Brazil’s e-commerce market is worth a hefty $14 billion a year.

“A mobile-first strategy is now essential in many markets,” says Simon Cotterrell, executive director of strategy at Interbrand. “Sixty six per cent of digital purchases were made through mobile phones in China last year, representing $450 billion.”

The idea of manifest destiny in the digital era materialises when corporations in the West describe e-commerce innovation in emerging economies as disruptive. “Oddly the markets where the most change is happening are less about disruption and more about construction,” says Tom Goodwin, head of innovation at Zenith USA.

“The acceleration in e-commerce in India and China is a reflection on countries that have leapfrogged the West’s retail model and built instead for the digital age. The explosion in the value of transactions online is due largely to nations building retail as a concept for the first time.”

Certainly, the mobile-first model is one that’s driving the powerhouse of Alibaba to expand beyond China into South-East Asia. This is also a blueprint that more established markets can learn from. “Innovation in China involves the combining of social, e-commerce, messaging and payment services under the roof of single providers. WeChat and AliPay are notable examples,” explains Hugh Fletcher, global head of innovation at Salmon.

“These are both beneficial to the user, but also beneficial to the organisation that owns the platform because it reduces the reasons for a user to leave. Western retailers need to take note of the rise of organisations offering multiple services through their platforms.”

In many ways, the emerging markets are the future. Like the California of the pioneering days, here attitudes are freer, less tied to conventional thinking and legacy systems. The major emerging economies are also more technologically free. Some call them traditionally futuristic. Their digital adoption is non-linear, hence the proliferation of mobile.

Brands born in the digital age are naturally collaborating globally as part of their corporate entrepreneurial DNA

“In the West, personal digital real estate is still fragmented. While we might shop with Amazon online, our grocery shopping is normally with another provider, our messaging and music with another, our payment too,” says Mr Fletcher.

“Western consumers like to consider themselves advanced, yet the linear growth of retail has burdened them with historic brand affiliations and nostalgia. Tech adoption also takes a more gradual, linear path, resulting in fewer revolutionary changes.”

The real manifest destiny of e-commerce is probably a meeting of minds, both West and East. “Brands born in the digital age are naturally collaborating globally as part of their corporate entrepreneurial DNA and are also considering localised operations as the way to meet new customer needs,” Michelle Du Prat, strategy director at Household, concludes. “This is where the future lies.”