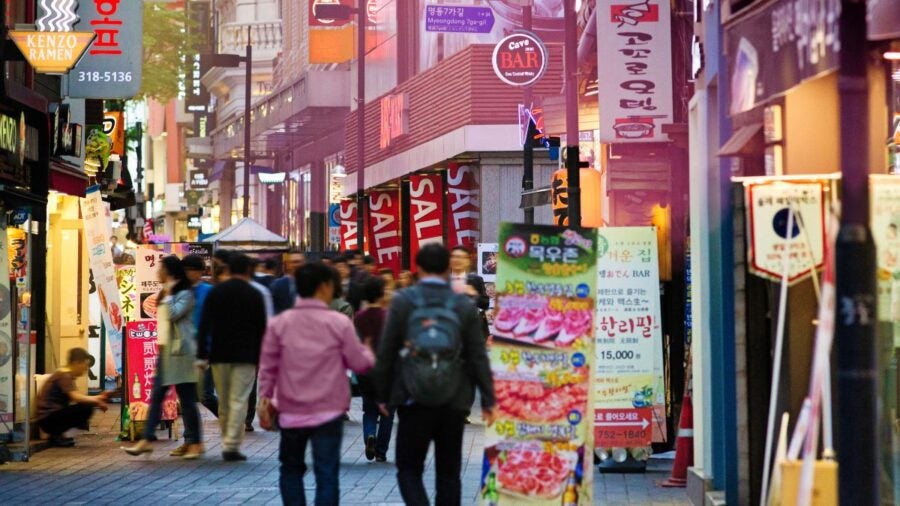

The Korean Wave, or Hallyu, has seen an explosion in the popularity of South Korean culture across the world. Alongside this interest in K-pop and Korean fashion, TV and film, opportunities to work in the Asian country are on the rise.

The past two decades have seen an upward trend in people deciding to move to South Korea – the current net migration rate stands at 0.39 per 1,000 people, a 8.94% increase from 2022. But despite becoming a more multicultural society, the country remains predominantly homogeneous, with non-Koreans accounting for just over 4% of the overall population of around 51.4 million in 2022. Only 13% of the foreign population in South Korea is from North America, Europe and Oceania.

South Korea is deeply attached to its culture, both modern and traditional, which for Justine Laguerre, a marketeer in the luxury industry based in Seoul for the past two years, is a source of fascination. “For curious visitors, Korea can feel like a place with a never-ending list of things to discover, learn or eat,” she says, but she also emphasises the importance of educating oneself about the country before deciding to settle.

“Get ready to both enjoy your life and endure hardship, because you will, as all expatriates do. Don’t come for the Korean Wave, because [the images we see in] K-dramas, K-pop and K-movies are not always accurate.”

What if I don’t speak Korean?

Despite Korean being one of the most popular languages to study – it’s the seventh most chosen on Duolingo in 2023 – it is also considered one of the most difficult languages to learn for native English speakers, which can make moving to the country for work seem daunting.

Don’t come for the Korean Wave, because the images we see in K-dramas, K-pop and K-movies are not always accurate

For Ross Harman, who has been working in South Korea since 2019 as a tax and corporate lawyer, this need not be a disadvantage if you are realistic about your limitations. “It is absolutely possible to get a good job and have a thriving career in Korea as a non-Korean. But the more Korean you can speak, of course the easier your life will be,” he says.

But Laguerre warns that foreigners who do not commit to learning the Korean language or embracing the culture may find their life there to be “quite superficial”.

South Koreans are highly educated and English is widely understood, especially in Seoul. But expats should not expect English to be used in the workplace for their benefit, especially in non-international companies. Unless you want to work as an English teacher (which now requires qualifications in reputable establishments), the days of arriving in South Korea with no skills other than speaking English are long gone.

How easy is it to get a South Korean work visa?

While South Korea has traditionally been reluctant to accept large numbers of immigrants, attitudes are slowly changing. Experiences vary but obtaining a work visa can be fairly straightforward if you have the correct paperwork, which can be quite extensive.

According to Heejoong Kim, an administrative attorney at OpenVisa Korea, the biggest driving force behind this rethink is the declining birth rate, as fertility rates in the country are at their lowest levels since records began, and it is eager to fill labour gaps.

“Beyond addressing the demographic challenge, foreigners bring diverse perspectives and creativity to businesses and Korean society as a whole. This is essential for Korean companies to thrive in the global economy,” he says.

Foreign migrant workers are in huge demand, so much so that the government recently made the unprecedented decision to increase the quota of visas for foreign “skilled” workers to 35,000, up from 2,000 the previous year.

Foreign professionals with specialised knowledge, such as professors, engineers and experts in specific fields such as IT, finance and marketing, are often sought after, as are English teachers from Anglophone countries.

Much of the South Korean economy is based on added-value exports, which means there is always a need for highly skilled technicians and engineers. In essence, the greater your perceived contribution to the economy, the easier it will be to find work.

Why hire a non-Korean?

But under the E7 visa – the visa most regularly used by employers when directly hiring foreign professionals – rules stipulate that the total number of foreigners employed by a company should not exceed 20% of the total number of domestic employees within that company.

Foreigners bring diverse perspectives and creativity to businesses… This is essential for Korean companies to thrive

This means that for foreigners seeking office jobs, one must carefully consider why a company would prefer to hire a foreigner over a Korean. While the rule doesn’t apply to all industries, and there are exceptions depending on the nature of the business and visa type, having a company vouching for the foreign hire during the visa application process most definitely helps.

“There is no shortage of high-quality potential Korean hires,” says Harman, recommending that jobseekers apply for positions including, but not limited to, those related to business development and marketing to international clients, companies that require a professional ability in English, or any job whose primary purpose is to promote links between Korea and other countries.

South Korea’s challenging working culture

For Laguerre, working in South Korea can be challenging, frustrating, upsetting and rewarding all at once. “Working in a country with such a strong work ethic and a different culture allows me to learn new things every day and to keep an open mind about life. It’s also a way to get to know Korean people and how warm they can be,” she says.

The country has a reputation for working long hours and work-from-home arrangements are not commonplace. Social hierarchy is also embedded within social and work life, which can make it difficult to express disagreement.

In recent years, there has been a pushback against such a culture, with young Koreans demanding shorter hours. Changes are slowly taking place and a proposed government policy to allow a 69-hour working week did not go as planned, necessitating a strategy rethink.

Elena Gerasimenko, who has worked at several Korean companies and now works for a small IT firm, is grateful to have found a “great company” but admits she has found adapting to the work culture difficult.

“Koreans love corporate dinners, but they are often burdensome. Saying no to these, which usually include highly encouraged alcohol consumption and might take place once a week, is considered bad manners,” she says.

By law, workers in South Korea are entitled to 15 days’ paid leave a year. In reality, most Koreans do not or cannot use all of them, due to nunchi – the awareness of what others may think.

“The worst is the unspoken rule of not being able to take more than four days off at once. For foreigners it’s often different, if the boss is understanding, you might manage to get almost two weeks off to visit home,” Gerasimenko adds.

Samsung Electronics, the country’s largest employer and often considered a trendsetter, is testing a four-day working week once a month. If successful, it could pave the way for other companies to follow suit.

Lack of diversity in Korean businesses

South Korea is still largely conservative and experiences as a foreigner in South Korea can be influenced by factors such as perceived social status, skin colour, country of origin and gender.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that I get less respect and have fewer opportunities than I would if I were white or Korean,” says Mohammad*, who is fluent in Korean and has a Muslim background. “Diversity and inclusivity simply don’t matter here. Nobody wants diverse teams or diversity in leadership,” he claims.

Working in a country with such a strong work ethic and a different culture allows me to learn new things every day

Many South Koreans also hold conservative attitudes towards the LGBTQ+ community. According to a Gallup Korea poll conducted in May, 42% of South Koreans believe homosexuality is “not a form of love” – this figure is higher among older generations. Politicians both left and right openly oppose homosexuality, including the current mayor of Seoul, who this year sided with attempts to block Seoul Pride from taking place.

South Korea is also one of only eight countries not to have a dedicated anti-discrimination law.

The country is steeped in patriarchy and the higher up the work ladder, the less visible women become. The country has consistently ranked worst for women to pursue equal opportunities in the workplace among the 29 countries surveyed for The Economist’s glass-ceiling index. Women are often expected, or made, to leave their companies after giving birth.

But for Laguerre, being a foreigner has been an advantage. “Korean people are both less strict and more open in their interactions with me, but I do know the situation is more complicated for my Korean friends in their 30s who struggle as women to find a place in the workplace – or just to be respected the same as any other male coworker.”

The cost of living in Seoul

Seoul was ranked the ninth most expensive city for expatriates in the world by global consulting firm ECA International.

Although core inflation in the country has slowed, many basic products remain more expensive than in recent years. Subway and bus fares are also set to increase for the first time in eight years. That said, proper budgeting and shopping at local markets can keep some costs down.

Pay varies but in 2021 the average monthly salary in South Korea was ₩3.33m (£2,000), while the average figure at a large conglomerate, like Samsung, was ₩5.63m (£3,379).

South Korea’s excellent logistics system means internet shopping is efficient, and Amazon Prime-like services such as Coupang deliver multiple times a day, sometimes within hours of ordering.

Unless your company provides accommodation or an allowance, expect to bring a hefty deposit if you plan to rent. There are two systems to consider, wolse and jeonse.

Wolse requires a deposit of around ₩10m to ₩20m for a one-bedroom studio that costs about ₩600,000 to ₩800,000 (£362 to £483 a month). For larger apartments or more expensive areas, this deposit can jump to between ₩50m and ₩100m (£30,159 to £60,318).

The jeonse system, although not as popular as it was, involves a significantly larger deposit that is often close to the value of the property itself, around ₩200m to ₩500m (£120,636 to £301,589) for a one-bedroom studio. But the benefit of the jeonse system is that no monthly rent is required during the lease term.

Medical care is excellent and generally a 7.09% rate (which is increasing annually because of the ageing population) of your monthly salary is applied to pay for national health insurance, half of which is contributed by your company if you are in full-time employment.

This means that medical costs are never prohibitively expensive and you are never far from a specialist clinic that can see you almost immediately. Several large hospitals provide multilingual services for larger procedures.

Convenience of living South Korea

Seoul is one of the most “liveable” cities in Asia, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit. Gerasimenko cherishes the convenience of living in South Korea, especially when you speak some Korean.

Public transportation is well developed, affordable and clean. Customer service is polite and friendly. The country has high-speed internet and public Wi-Fi in many places.

There is a variety of food delivery and online services, although many are not available in English. Even on a standard salary, there are plenty of reasonably priced local eateries. But don’t expect too many to cater to dietary considerations such as vegetarianism or religious dietary requirements.

Seoul can be a playground for going out, from partying in the international district of Itaewon and high-end dining in Gangnam, to street drinking in Jongno or weekend hiking in the stunning Bukhansan National Park right on the city’s doorstep, there’s something for everyone.

Comparative safety is often regarded as an additional benefit of living in South Korea, despite worried parents back home often fearing that a nuclear war with North Korea is imminent.

“My favourite part is that you can leave your personal belongings anywhere, and there is a high chance they will still be there when you come back. One of the main reasons I stay in Korea is because I feel safe. I don’t feel I need to take pepper spray with me each time I go outside,” Gerasimenko says.

Ultimately, living and working in Seoul is all about striking a balance and understanding the pros and cons that come with living in such a vibrant and fascinating city. “No matter how nice people are and how many services are available for foreigners, because of huge cultural differences, I cannot help but feel alienated at times,” Gerasimenko adds. “But this is nothing compared to what Korea has given me.”

You can read more from our Working Around the World series here.

*Name changed