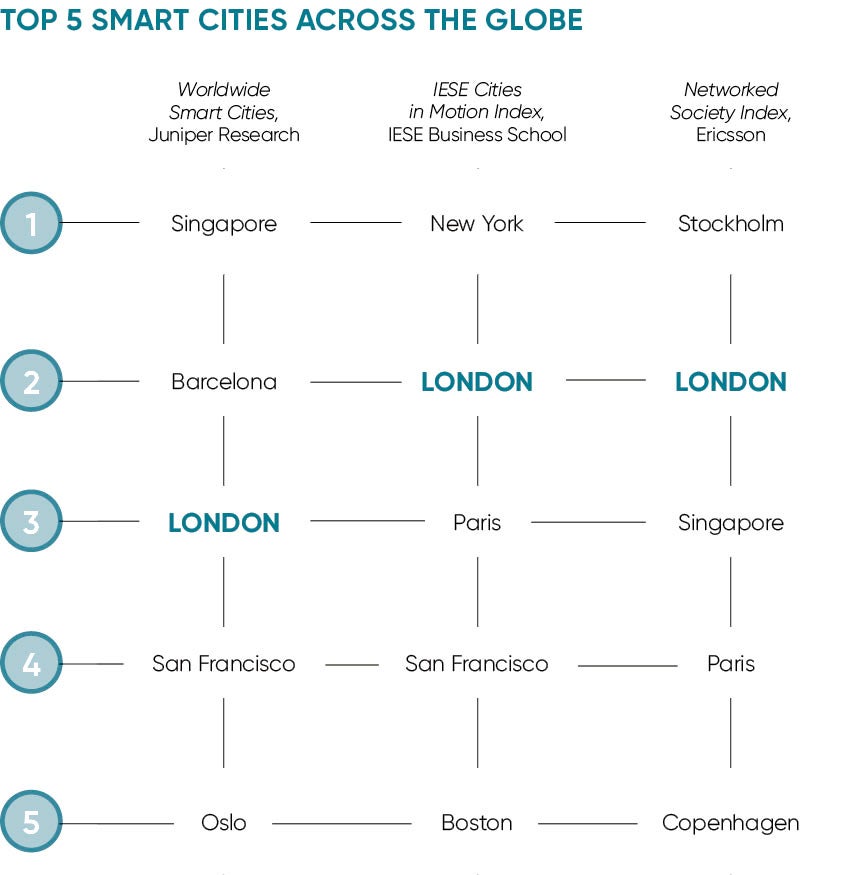

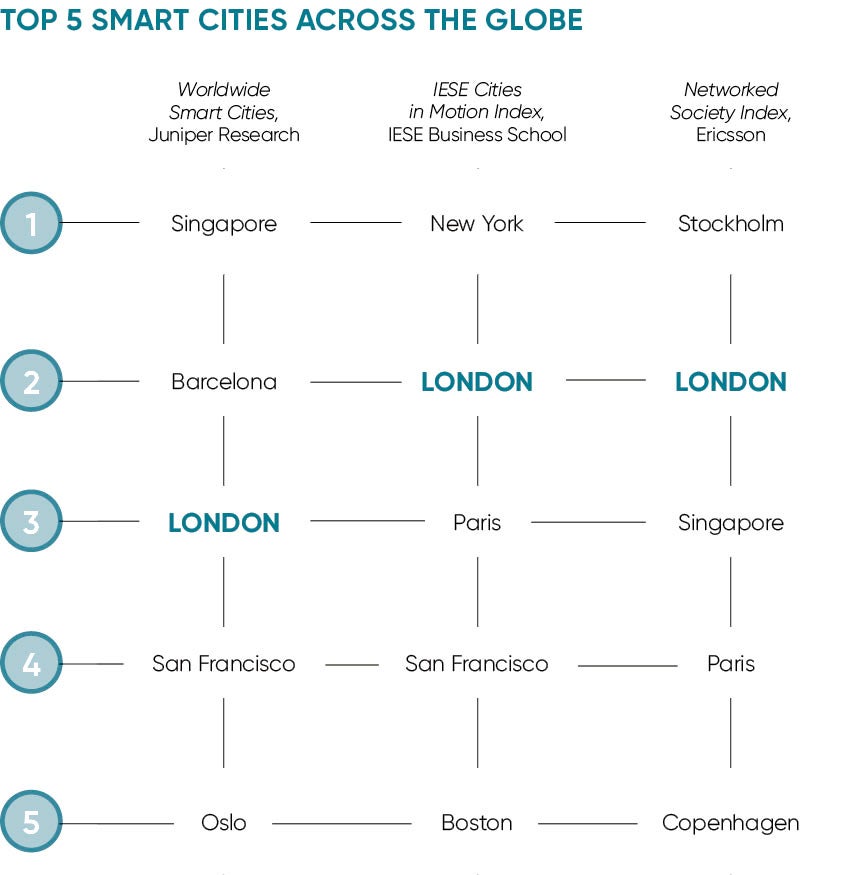

Take a look at the current smart city league tables and you’ll see that London is doing well. Third behind Singapore and Barcelona, according to research firm Juniper; second behind New York in the IESE Business School’s rankings; and second again, this time behind Stockholm, according to Ericsson’s Networked Society Index.

But, as the small print on investment products warns us, past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Maintaining that standing in the years and decades to come will be anything but straightforward, especially if you consider the “low-growth, no-growth” economic backdrop in developed Western economies and the ambitious plans for settlements such as Yinchuan, China’s blueprint for smart cities.

Another consideration is, of course, what it means to be a “smart city”. The term brings to mind futuristic digital technology – instead of using an Oyster card, Yinchuan residents already access public transport with facial recognition software – but it might be more helpful to think in terms of “future cities”, says Scott Cain, chief business officer of the government’s Future Cities Catapult.

“A future city is one that is adaptive to the changing needs of its citizens. It’s about how it understands those needs and responds to them using innovations, some of which would be digital, while others would be to do with governance, finance, business and any number of other factors.”

Crucial to London’s continuing success, says Amanda Clack, head of infrastructure at EY, will be its ability to recognise what type of city it is and what that means for its development. She outlines four categories of global cities from “new” (such as Songdo in South Korea and Shenzhen in China), to “experimental” (Singapore and Hong Kong), “developing” (Rio and Lagos) and “evolving” (New York, Tokyo and London).

While there might be benefits from effectively building something from the ground up – Shenzhen, for example, has gone from having a population of around 30,000 in 1979 to more than ten million today – more historical cities aren’t necessarily at a disadvantage. “In London we have some interesting constraints,” says Ms Clack. “But some of them also bring opportunity.”

Smart data

One of the main tools would-be smart cities have at their disposal is data. But the way in which it’s used needs to evolve, according to Andrew Collinge, smart city lead for the Greater London Authority (GLA). “We go nowhere without a mature approach to city data,” he says.

“In the past we tended to focus on ‘open data’, but that only gets us so far towards our ambitions. I want us to consider using less data, but data with strongly predetermined uses. So rather than fishing in a data lake, I’d prefer to have a data puddle in which it’s much easier to catch something.”

It might be necessary to make certain tranches of data available to certain organisations, Mr Collinge adds. Although he acknowledges how concerns about privacy and competition need to be carefully considered.

Regular changes of leadership and political plurality make long-termism more difficult

“One of the key measures of success is that it’s linked to political priority,” says Mr Collinge, whose role includes oversight of the newly established London Office of Data Analytics. But the tendency for discrete groups of people to have separate discussions about data, or technology, policy or politics is too prevalent for his liking. “We have to connect those things,” he says.

Mr Collinge says his office has a two-way relationship with the London mayor’s. Suggestions about projects and policy pass in both directions, and this way of working has already helped to apply data analysis to the issue of rogue landlords and multiple occupancy.

Other data-related advances might include smart energy grids, “wayfinding” enabled by improved connectivity in public spaces and energy-efficient LED street lights. But it would be disastrous to ignore the human element of the equation, says Mr Collinge. “Half of cities’ budgets are spent on adult social care,” he points out.

Internal infrastructure

The single most important factor in making progress, however, might be a change of outlook. “Eighty per cent of this is a cultural battle with senior managerial and political leadership in the city, which is about acknowledging that capacity needs to increase in organisations with regard to competencies like data science. The other 20 per cent is the technology and the data – how you harmonise it and how you store it effectively,” says Mr Collinge.

Improving city dwellers’ quality of life and opportunity isn’t just a matter for public bodies, businesses have a role to play too

EY’s Ms Clack extols the importance of a “30-year vision”, something that places such as Dubai and Hong Kong can bake in to their plans, but which a city like London could struggle with. Regular changes of leadership and political plurality make such long-termism more difficult. The architecture of local government and the 33 London boroughs can make things tricky too, but Ms Clack points to the cohesion of the capital-wide Transport for London as proof that the difficulties can be overcome.

“We should just merge the GLA and the City of London. It’s anachronistic in the extreme,” says Mr Cain at the Future Cities Catapult, which aims to bring together business, academia and politicians to “make cities better”. He argues eliminating some of inefficiencies that result from having one organisation to oversee the Square Mile and another for the rest of London would free up funds to invest in infrastructure and technology. Further down the line, he suggests, it might even pay to consider “devo-max for London”.

The private sector

But, he says, improving city dwellers’ quality of life and opportunity isn’t just a matter for public bodies, businesses have a role to play too. Take OpenPlay, a company that connects people to open spaces and with the people or organisations that facilitate activities. Or there’s GoodGym, which provides a framework and opportunities to combine exercise with volunteering. And Spacehive, a crowdfunder for civic projects that might inspire a wave of “imbyism”, instead of nimbyism; people who want worthwhile projects in (or near) their own back yards.

Another crucial factor will be how quickly certain technology can be integrated into large, permanent developments, says Laurence Kemball-Cook, founder of London-based cleantech firm Pavegen. The company produces paving tiles that can convert the kinetic energy from pedestrians’ footsteps into electrical energy and hopes to offer more functionality soon, such as the ability to provide data about the way people move around a city. “As more connected Pavegens go into the ground, the data they produce becomes more valuable to the people interacting with them and the wider community,” he says.

Mr Cain says London’s “crown jewels” are its world-class academic institutions and the access to talent that it enjoys via proximity to Oxford and Cambridge. What’s more, he says, the capital’s adaptability bodes well for its future. The way the new East London Overground line became part of the wider TfL network in 2010 and the manner in which the initially unpopular Congestion Charge soon became a success support his point. “If we could package the Congestion Charge and sell it as an end-to-end solution, so many cities would want to buy it,” he says.

And, while China and other Asian countries might be preparing cities that will “magically rise out of the fields” with “pipes that are laid in uniformity and infrastructure that is just there”, the GLA’s Mr Collinge doesn’t think Londoners should be too jealous. “They’re pretty soulless, lifeless places that don’t produce much by the way of economic, social and environmental value,” he says. “Yes, of course we have problems with London’s infrastructure and retrofitting digital technology to it. But I’d rather have that problem than have an empty field in which to build this stuff – no matter how much money I have.”

Smart data