Once upon a time there was a clean, clear link between a country’s wealth and a company’s desire to tap into its consumer base. Whether you were McDonald’s or GSK, Volkswagen or Marks & Spencer, a new market offered access to a large group of people who would, at some point, want to buy a burger, medicine, a sturdy hatchback and a dressing gown.

Then corporates started becoming sophisticated. No two markets, they realised, were the same. Wealth might be concentrated in the hands of young people in one region – say, Africa – but reside in the wallets of the middle aged or elderly in Japan or northern Europe. In yet other markets, the United States being a classic example, consumption was and is spread across a broad demographic and geographic range.

Understanding demographics

To corporations that package and sell goods and services, and to the investors who own shares in them, having a solid understanding of demographics in a target market is of paramount importance. Getting it right can define whether that company rises and grows, or fails and falls. Whether you enter market A or market B – or both, plus markets C, D and E – may depend on a welter of hellishly complex variables.

For one thing, what are “good” demographics? To some economists, this is all that matters. Germany’s “economic miracle”, which revived a shattered economy in the 1950s, was built on the shoulders of driven group of young entrepreneurs desperate for a better life. The same factors later put a rocket under growth in Japan, South Korea and China.

To Brian Pallas, the founder of Opportunity Network, a global match-making service for investors, demographics are becoming evermore relevant for decision-makers at corporations. “When deploying capital, you are looking for growth. It doesn’t matter where an economy’s baseline is, so much as how fast it’s growing,” he says.

Yet demographics are often only part of the picture. Having a bustling young population helps, but not if it would rather be engaged in embezzlement rather than job creation.

Bad government, corruption, shoddy infrastructure and incomplete legal or judicial systems can all hamper a country’s potential, or hinder its rise. “Good demographics are certainly a plus, but they aren’t a guarantee of success,” says David McIlroy, who manages the Africa fund at London-based Alquity Investment Fund, with £65 million in assets under management.

Marcus Svedberg, chief economist at emerging-market investment manager East Capital, adds: “You can fail with good demographics, just as you can succeed if your demographics look bad.”

Sub-Saharan Africa

A classic example here is sub-Saharan Africa, which by any measure has the world’s best demographics. The region boasts 11 of the world’s 20 fastest-growing economies, and a wealth of human and natural resources. By mid-century, Nigeria is on track to become the world’s third most populous nation after India and China, with Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda all set to pass the 100-million mark.

Urbanisation is rising across the region, a process that raises growth and employment, and boosts disposable income and consumption, factors that act as fly-paper to investors and corporates. Alquity’s Mr McIlroy says his fund is investing in corporates that produce goods ranging from soft food to telecoms to cement. Included in its Africa fund are major corporates, such as South African media firm Naspers, Egyptian food producer Edita and Nigerian cement giant Dangote.

Yet Africa also lags horribly. It had great demographics in the 1990s and 2000s, but progress was thwarted by corruption and war. Even now, shockingly bad infrastructure undermines growth. This can be seen as a risk or an opportunity, but if the region is to realise its full potential, it will have to up its game. Mr McIlroy points to another fast-growing region as a guide to a sunnier future. “Look at what Asia did to make itself a success,” he says. “Better education and more jobs created across labour-intensive industries. African governments need to follow that playbook.”

To some companies and investors, good demographics can mean old and rich, rather than young and striving

India, Vietnam

Other nations have demographics that will perhaps never be bettered. India, projected to overtake China as the world’s most populous nation by 2028, “will benefit from a demographic boom for decades to come, as more people enter the workforce, becoming the consumers of tomorrow”, says Mike Sell, head of Asian investments at Alquity. Much of this will depend on the current premier, Narendra Modi, succeeding in his quest to create enough manufacturing jobs to meet the needs of millions of young college graduates and blue-collar workers.

Then there’s Vietnam, a country that boasts low labour costs and 90 million young, free-spending consumers, yet which remains, adds Mr Sell, “perennially ignored by investors”. To Hedi Ben Mlouka, who manages the emerging-market frontier fund at Duet Group, a £3.6-billion asset manager, Vietnam will “reap the benefits” of bullish demographics for years to come. “A burgeoning middle class is the catalyst for consumer demand,” he says. “Investors should look at consumer names with strong balance sheets, good brand visibility and market knowledge, such as Vinamilk and Mobile World Group.”

Looking out for signs

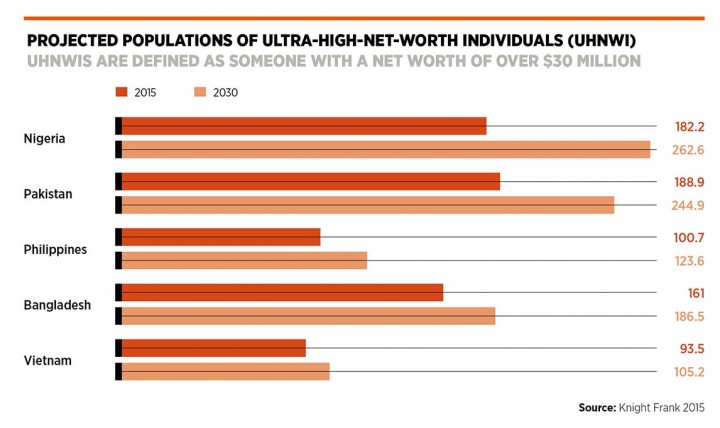

These are the sorts of countries East Capital’s Mr Svedberg is looking at when he adds listed securities to his new £45-million Global Frontier Fund. “We look for signs of people buying things – first, a car and an apartment, then a smartphone and a trip to IKEA,” he says. “This is when we know that a market is doing well.” Markets in this bracket include the likes of Saudi Arabia, Colombia and Pakistan. The corollary of this is Russia, which with its ageing, unhealthy workforce has “some of the worst demographics on the planet”, adds Mr Svedberg. Other nations facing negative demographics include Turkey, Brazil and China.

To some companies and investors, good demographics can mean old and rich, rather than young and striving. A host of funds and companies have sprung up in recent years, catering to ageing Western societies where wealth typically rises in lockstep with age.

Johan Utterman manages Lombard Odier’s $475-million Golden Age fund, which invests in markets and opportunities dominated by senior citizens and baby boomers. A pioneer in this field, Mr Utterman’s fund invests overwhelmingly in sectors such as healthcare, financials and leisure, which cater for long holidays and creaky knees. The fund generated a return of 10.78 per cent in the first seven months of 2015, against a benchmark market return of 6.37 per cent, thanks to outperforming shares in companies such as pet healthcare provider Antech and pharmaceutical firm Allergan, which makes drugs that target schizophrenia and osteoporosis.

Mr Utterman’s method is to find out which markets – typically found in north-east Asia, Europe and North America – that are rich and dominated by older citizens, and then find local securities in which to invest. “Life expectancy is increasing by up to a hundred days in a single year in some markets,” he says. “In others, up to three-quarters of that country’s net financial worth is in the hands of baby boomers and seniors.” This thinking explains the fund’s decision to buy shares in Harley-Davidson, which has begun to roll out motorbikes with heated seats and a reverse gear. The reason? The average age of new hog buyers is now 52.

And the stock picking gets more nuanced. The Golden Age fund also invests in business-to-business firms. So it buys shares in, for instance, Croda International, a specialist British chemicals firm that produces complex anti-ageing creams. It owns shares in Resort Trust, a huge owner of golf courses, as well as Toro, an American maker of industrial lawnmowers, which maintain those golf courses. And longer lives don’t just influence what products a company makes, they also affect how a firm is run. Opportunity Network’s Mr Pallas notes that by 2050 the average German will be in their mid-50s. “That affects careers,” he says. “It means that CEOs will stay at the helm for far longer.”

When the world was smaller and poorer, demographics used to be easy. Markets typically offered companies wealth and growth prospects, or neither. These days, getting your product mix and your market penetration right is harder and more complex than ever before – but also far more rewarding and profitable.