It is perhaps the biggest issue facing British business in the coming years. Will Britain remain part of the European Union or will voters choose exit, leaving the country to forge new economic relationships both with Europe and with the rest of the world? It could happen sooner than people think. Though Prime Minister David Cameron’s commitment is to hold an in-out referendum before the end of 2017, expectations are growing that the vote will take place during 2016.

As far as business is concerned, the battle lines are growing. Business for New Europe, which counts much of Britain’s business establishment among its membership, including high-profile figures such as Virgin’s Sir Richard Branson and WPP’s Sir Martin Sorrell, argues that “Brexit” – British exit from the EU – would deprive business of unrestricted access to its most important market.

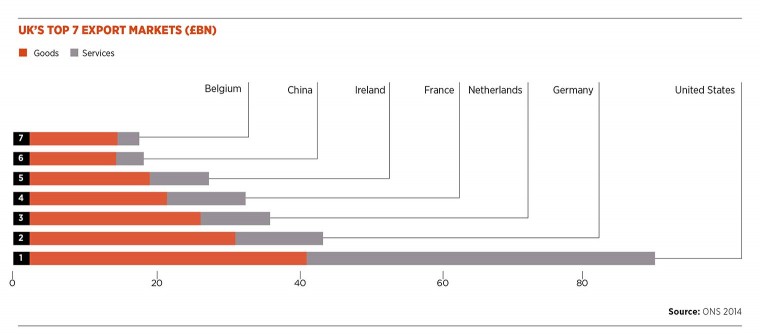

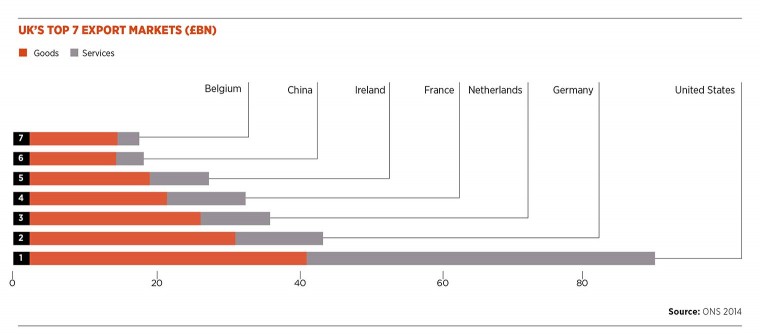

It says: “As a member of the European Union, our companies can sell, without barriers, to a market of 500 million people. The Single Market means that exporters only need to abide by one set of European regulations, instead of 28 national ones. Europe is our biggest trading partner – it buys 45 per cent of our exports. If we left the EU, companies would face tariffs and regulatory barriers to trade. The free movement of capital means that EU companies can invest here in Britain freely. This investment, by companies such as Siemens, creates jobs and grows our economy. Forty six per cent of all the foreign investment in Britain comes from EU countries.”

Making the EU more competitive

While backing the Prime Minister’s efforts to renegotiate Britain’s membership and to make the EU “more streamlined and competitive”, it says that such reform would be impossible if Britain was “outside knocking on the door”. British households benefit to the tune of £3,000 a year from EU membership, Business for New Europe claims, and the UK gains from free trade deals negotiated by the EU with more than 50 other countries.

Such claims are challenged by others, most notably Business for Britain, led by its chief executive Matthew Elliott, and which includes John Mills, the Labour donor and chairman and founder of JML among its prominent supporters. Business for Britain claims to speak for “the silent majority” among British businesses, though its stance is not explicitly one of campaigning for EU exit.

It says: “Business for Britain will ensure that the British people understand that many UK business people want a better deal from Brussels and are not scared to fight to achieve that change.” But it also insists: “Instead of pushing the debate to the extreme corners of In versus Out, we should be having a sensible discussion about what is right and what is wrong in our current arrangements.” However, it is expected to push for exit if it deems the Prime Minister’s renegotiation efforts are unsuccessful.

Escaping the red tape

In contrast to Business for New Europe, Business for Britain says the UK could gain influence and prosper outside an unreformed EU. Business would escape most of the red tape imposed as a consequence of membership, new trade deals would be negotiated with the rest of the world and families would gain to the tune of £933 a year, mainly through not being subject to high food prices as a result of the Common Agricultural Policy. It has produced a 1,000-page report, Change or Go, to set out the case for a British future outside an unreformed EU.

One thing that is clear is the run-up to the referendum will produce some uncertainty and a decision to leave would provoke even greater uncertainty

Where does the truth lie? Cost-benefit assessments of EU membership assembled by the House of Commons Library do not provide a definitive answer. The Centre for European Reform suggested that the effects of staying in or leaving the EU would be relatively small, ranging from a negative 2.2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) to a positive 1.55 per cent by 2030.

But it concluded: “The alternatives to EU membership are unsatisfactory: they either give Britain less control over regulation than it currently enjoys, or they offer more control but less market access. In a referendum, Britain will have to choose between national sovereignty and unimpeded access to EU markets. While membership of the EU is as much about broader, political questions as economics, the economic case for staying in the Union is strong.”

A 2014 report by the London School of Economics’ Centre for Economic Performance suggested that the trade costs of leaving the EU would range from 2.2 to 9.5 per cent of GDP, though a report from Civitas, the think tank, suggested the trade benefits of EU membership were greatly exaggerated. In a 2013 assessment, the CBI, representing employers, said the overall net benefits of membership ranged from 4 to 5 per cent of GDP.

Uncertain times

That debate will go on and will become more intense. One thing that is clear is the run-up to the referendum will produce some uncertainty and a decision to leave would provoke even greater uncertainty. Negotiating and adjusting to new arrangements outside the EU could take a decade. The biggest threat would be to investment, particularly inward investment into Britain from outside Europe, much of it done with an eye on accessing Europe’s single market. British business could also decide to invest elsewhere in the EU, however, to ensure it is within the single-market area.

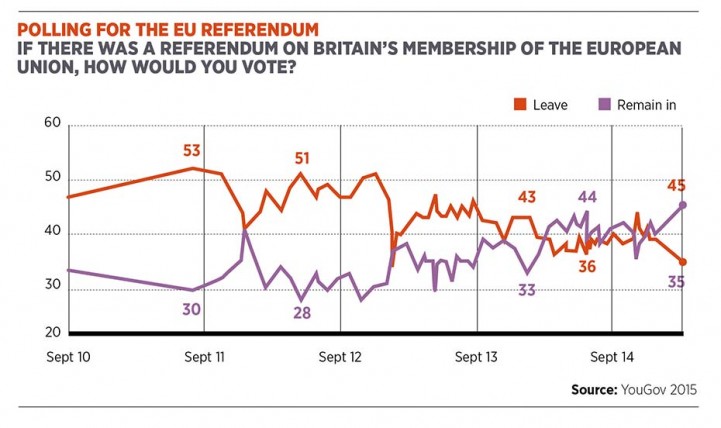

The debate has a long way to run and public opinion can and probably will change before the referendum takes place. The only precedent, as far as Britain is concerned, is the 1975 referendum on Britain’s continued membership of the European Economic Community (EEC), called by Harold Wilson’s Labour government.

When the referendum was called, in January 1975, the public appeared on balance hostile to continued membership, by 60 to 40 per cent. In the referendum itself in June, however, the vote was two to one in favour of remaining in the EEC; 67 to 33 per cent. The parallels are not perfect. Business was strongly in favour and provided much of the funding for the “Yes” campaign. Newspapers and mainstream political opinion also campaigned to stay in.

This time will be different but, as things stand, and despite the bitter battle leading up to the latest Greek bailout and the EU’s migration crisis, the debate starts with public opinion in favour of continued EU membership.

Polls show growing support

YouGov suggests public opinion on membership, which as recently as 2012 showed that the proportion of people wanting to leave the EU exceeded those supporting continued membership by 20 percentage points, has turned around. So far this year, its polls have shown voters are in favour of remaining part of the EU, the latest by 45 to 37 per cent.

The two most important drivers of public opinion on EU membership appear to be the state of the eurozone economy and UK consumer confidence. In 2012, the euro looked to be on the brink of break-up and consumer confidence in Britain was at a low ebb. People blamed the EU’s woes for their own economic discomfort. This year the eurozone economy has been recovering, albeit slowly, and a messy Greek deal has been done to avert break-up. More importantly, UK consumer confidence is riding high, having recovered to pre-crisis levels and beyond.

There is a long way to go but for those who see Britain’s future best served outside the EU, including business campaigners, the task will be to turn around public opinion, not ride a tide of anti-EU sentiment.