Is Australia a world leader in whistleblower protection? The government claimed so, following a new act passed in 2019, which introduced a raft of modern protections.

At a stroke Australia’s regime for reporting corporate misbehaviour was transformed. The Treasury Laws Amendment (enhancing Whistleblower Protections) Act 2019 unquestionably enhanced the legal rights of whistleblowers. It also imposed significant new responsibilities on companies trading in Australia.

“It’s a quantum leap, a game-changer,” says Professor A.J. Brown, director of Griffith University’s anti-corruption programme and board member of Transparency International, who advised on the legislation.

But there are detractors. Critics argue the protections are not as strong as first claimed and in some cases illusory. The laws also exclude certain types of commercial entity, leaving some workers unprotected, while ambiguity in other areas will pose challenges for internal compliance teams.

Here’s what you need to know about Australia’s whistleblower debate.

What the law says

The 2019 act is a broad piece of legislation. There are seven key areas:

1. The range of people who enjoy protection is now much wider. Current or former officers, employees, contractors and individual associates are covered by the act. Even relatives, dependents and spouses or former spouses of these categories are included.

2. There are clear instructions on how a whistleblower must make a complaint. Contact can be made with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority or an “eligible recipient”, such as an officer or entity recognised by the company. This latter group can include an independent whistleblower service provider.

3. Emergency disclosures to parliamentarians and journalists are permitted. In this case, the whistleblower needs to believe there is imminent danger to the health or safety of one or more persons, or the natural environment.

4. Reports can be made anonymously. It was previously required that the identity of the person be disclosed, albeit confidentially. The penalty for breaching the confidentiality of the reporter now carries a civil penalty of A$10.5 million or, if a benefit derived, up to three times the benefit or 10 per cent of the annual company turnover up to A$525 million. Violators may also face criminal charges, punishable by imprisonment or fines.

5. A requirement to make disclosures in “good faith” is abolished. This requirement previously undermined whistleblowers if it could be implied they acted with ulterior motives against the company concerned. However, whistleblowers are still expected to have “reasonable grounds” for their disclosure.

6. Whistleblowers will be protected from reprisals. This provision, one of the act’s primary goals, demands companies take active steps to protect those who speak up. It includes a requirement for Australian companies to write a compliant whistleblower policy. This requirement affects public companies and large proprietary companies with more than 50 employees or A$12.5 million in assets. Section 1317AI(5) sets out the seven compulsory sections a compliant report must incorporate, including how the company will support whistleblowers and protect them from detriment.

7. The law on costs is changed. New protections from adverse cost orders for whistleblowers are included, except where claims are deemed vexatious or without reasonable cause. This makes the prospect of pursuing a claim less daunting for whistleblowers.

Ambiguities within the law

The act covers a lot of ground. So why might some organisations face difficulties interpreting it? A key reason is the caveats within the text. For example, there is a lack of clarity on specifically what is protected.

“One of the challenges for organisations is the broad scope of the act,” says Vince Rogers, partner and employment law specialist at law firm Ashurst. “It protects disclosures in cases of ‘misconduct’ or ‘improper state of affairs or circumstances’. This scope is very broad, certainly when you compare with how other jurisdictions define what can be subject to a protected disclosure.”

Although personal work-related grievances are excluded from the act, there is some ambiguity around what might constitute a significant enough exception to those guidelines, particularly in cases that might involve sexual harassment, bullying or discrimination.

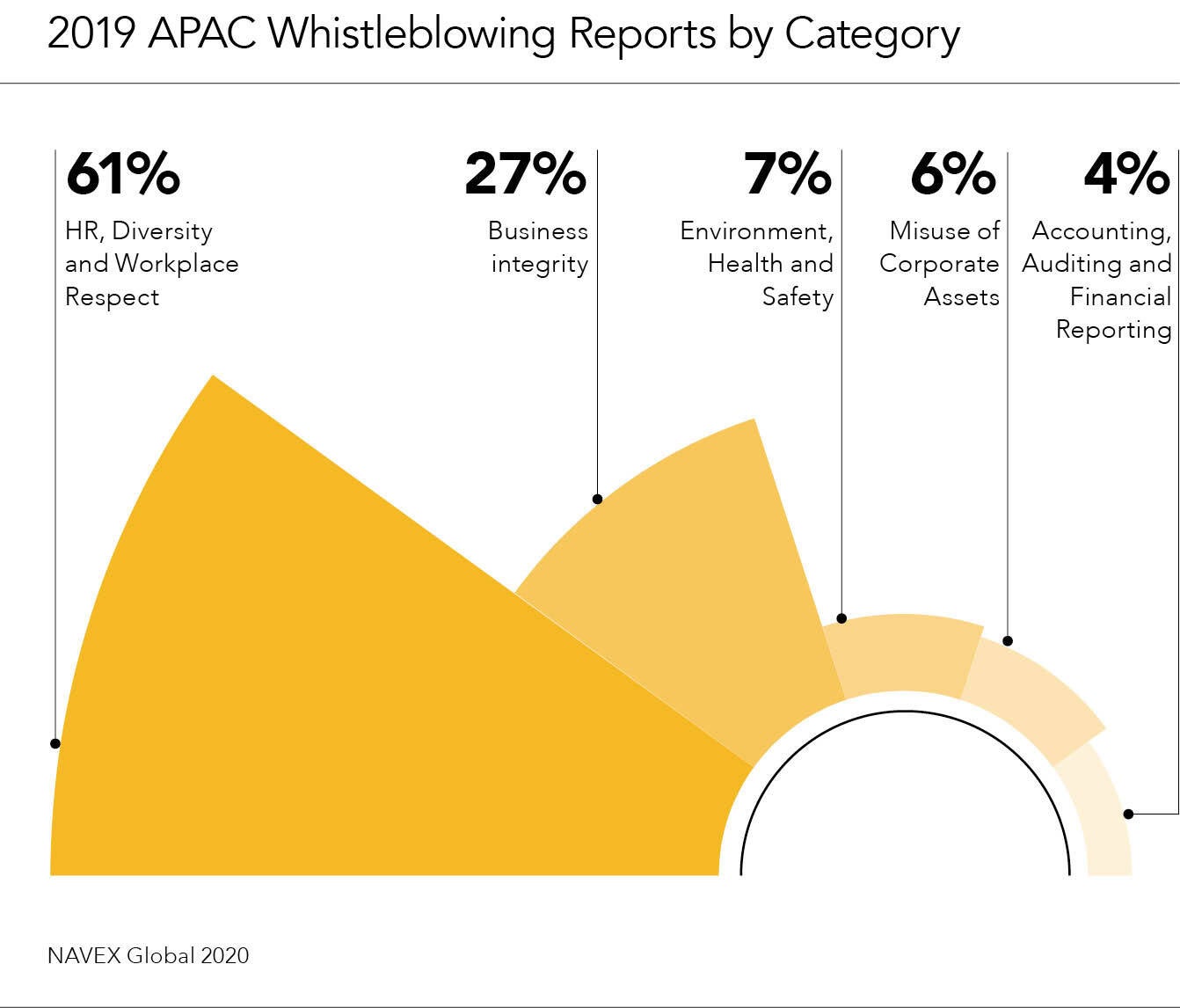

Given that almost two-thirds of all whistleblowing reports relate to human resources issues (NAVEX Global, 2020), this is an area that could create difficulties for many organisations.

What the act doesn’t include

Within the act there is no provision for a single agency to oversee whistleblowing. “One missing aspect is a government agency to support whistleblowers and issue guidance,” says Rogers. “The complexity now is we have one agency dealing with company legislation, another on prudential regulation of banks and financial services. If you are not in that sector, it defaults to ASIC, even though the subject matter of the disclosure may be something completely different.” Whistleblowers risk getting lost in a legal system they don’t understand, with little official help.

Whistleblowers risk getting lost in a legal system they don’t understand, with little official help

The act does exclude some commercial entities. Partnerships and anyone employed by a non-incorporated entity is not protected. That, say critics, is a serious omission. The public sector, meanwhile, is entirely excluded from the legislation.

And there are no bounties paid. There are advocates for amending the act to include whistleblower rewards, as is the case in the United States. But, for the time being, Australia looks set to follow the bounty-free approach currently favoured among European Union member states that are in the process of individually adopting the EU’s own whistleblower protection reforms.

Then there’s the issue of the onus of proof in the case of reprisals. In the fine print, there are significant qualifiers, which may nullify the effect. “There is a technical defect in the act,” says Brown at Griffith University in South East Queensland. “The onus of proof is on the company to prove a detrimental action wasn’t connected to the act of whistleblowing. But to order compensation the court must be satisfied the company or individual responsible had the whistleblowing in mind as part of the reason for their actions when acting in a detrimental way to the whistleblower. If they swear black and blue in court that it wasn’t the reason, it will be a challenge to prove otherwise.”

Despite the uncertainty, companies must comply

For companies that are yet to act, the requirements are, fortunately, extremely clear. The act places a strict obligation on companies to protect whistleblowers from reprisals, rather than react afterwards. “This is a world first,” says Brown. “It is a bit similar to the UK Bribery Act, whereby companies are under a positive obligation to show they have policies to prevent harm. Same principle.”

But the most fundamental obligation, for the majority of organisations at least, has been to implement a policy on whistleblowing before the 1 January 2020 deadline that’s compliant with the new rules. “We needed to update our policy as a result of the changes in Australia’s whistleblowing law,” says Brett Anderson, general manager of enterprise risk at Flight Centre, one of Australia’s largest travel companies.

“The majority of changes we made were to provide further clarity on specific elements within the policy, including providing more details to define a disclosable matter and who is eligible to receive those matters. We also provided further details regarding the protections offered to whistleblowers under the policy.”

A prudent path is to partner with a corporate risk specialist. The complexities of the new act mean only an expert in the field is likely to achieve full compliance.

Furthermore, working with an authorised whistleblowing service, which qualifies as an “eligible recipient” for direct receipt of disclosures, according to ASIC regulatory guidance, ensures corporate wrongdoing has a high chance of being exposed before it can lead to serious damage.

Flight Centre, for example, works with NAVEX Global. “We have found having a corporate partner like NAVEX Global is critical when it comes to running a whistleblower service suitable for each global region we operate in,” says Anderson. “NAVEX Global provides an easy-to-use solution to eligible whistleblowers to raise matters either confidentially or otherwise and for us to stay in touch with them as we manage the case.”

Working with an authorised whistleblowing service ensures wrongdoing can be exposed before causing serious damage

Indeed, maintaining confidentiality is critical for organisations. Challenges include obtaining consent from the whistleblower to disclose their identity to a restricted number of people directly involved in handling the report, having strict policies in place for those who receive and handle complaints and putting processes in place that protect the confidentiality of the whistleblower.

The future

The act has positioned Australia as a leader in whistleblower protection in the Asia-Pacific region. Hong Kong, for example, has no specific legislation for protecting or rewarding whistleblowers, although there are indirect protections. Meanwhile, a proposed update to Japan’s Whistleblower Protection Act, introduced in 2006, would at last see organisations penalised for violating it, but there’s no immediate prospect of increased protection from retaliatory measures.

However, Australia’s public sector provisions may need revisiting. In June 2019 a judge called the law “technical, obtuse and intractable” when presiding over a case of a security guard working for the Department of Parliamentary Services. Attorney-general Christian Porter promised to overhaul legislation to protect employees of the state.

Australia’s opposition Labor Party has vowed to revisit whistleblowing protections too, and add what they argue to be crucial missing elements within the new law, should they take power. The foundation of an agency to oversee enforcement and protect whistleblowers, and the introduction of US-style bounties, are likely to feature prominently.

A whistleblower hotline, in particular, can help protect the identity of those who report concerns and is likely to become a regular feature within organisations right across the country. In fact, the deployment of an independent whistleblowing system is positively encouraged by ASIC’s regulatory guidance, which states that by doing so “an entity may encourage more disclosures since disclosers can make their disclosure anonymously, confidentially and outside business hours; receive updates on the status of their disclosure while retaining anonymity; and provide additional information to the entity while retaining anonymity”.

With fines and possible imprisonment of executives who flout these principles, the deployment of a hotline system ought to be seen as a practical precaution.

Australia’s new law is a great improvement on past provision. Affected companies have been obliged to revisit their whistleblowing processes and take concrete action to comply with the act. But it’s clear that even for those who have taken the necessary steps, some ambiguity remains. And, with calls for further reform continuing, critics argue a return to the issue will be required before too long.

Taking a proactive approach to addressing your compliance risk will help protect your business, reputation and bottom line.

NAVEX Global can help.

We are the worldwide leader in integrated risk and compliance management software and services, and the world’s largest provider of whistleblowing systems.

Find out more at www.navexglobal.com

Is Australia a world leader in whistleblower protection? The government claimed so, following a new act passed in 2019, which introduced a raft of modern protections.

At a stroke Australia's regime for reporting corporate misbehaviour was transformed. The Treasury Laws Amendment (enhancing Whistleblower Protections) Act 2019 unquestionably enhanced the legal rights of whistleblowers. It also imposed significant new responsibilities on companies trading in Australia.

“It's a quantum leap, a game-changer,” says Professor A.J. Brown, director of Griffith University's anti-corruption programme and board member of Transparency International, who advised on the legislation.