Most businesses understand the need to protect networks and data assets if client trust and operational functionality are to be maintained. With the General Data Protection Regulation coming into force on May 25, failure to do so could lead to fines of up to €20 million or 4 per cent of global annual turnover. Ultimately it is all about protecting the bottom line. So why is there far less understanding about the role cyber-risk insurance can play?

Given that calculating cybersecurity risk exposure itself is complex, it shouldn’t be surprising insurers face difficulties in creating effective and affordable cyber-risk policies. Technology evolves quickly, as do use-case scenarios, and that’s making it increasingly difficult for both businesses and insurers to keep pace.

“Simply put, changes in technology affect how data is collected, stored and used, and the risks to which businesses are exposed as a result,” says Tim Smith, head of cyber at commercial law and insurance specialist BLM.

Data type and volume varies enormously from organisation to organisation, as does the risk represented. “Assessing that risk, identifying what the exposures are, then working out how much of that risk the company wants to manage through an insurance product is not straightforward,” says Mr Smith. Unlike motor insurance, for example, there isn’t a century of claims data to fall back upon.

As the cyber-loss experience becomes less benign, insurers are expected to start insisting on much more qualified risk-exposure data. “Until then insurers are compensating for the problems in submitted exposure data using ‘outside-in’ third-party data sources, such as cyber-incident data pools and measures of vulnerability of internet exposed IT infrastructure,” says Pratap Tambe, business development manager at Tata Consultancy Services.

This is hugely problematical, certainly according to some cybersecurity vendors. Take Nik Whitfield, chief executive at Panaseer, who argues that outside-in is a highly limited approach “similar to doctors assessing patients without the benefit of X-rays, blood tests or MRI scans”.

Better to be using “inside-out” information for risk assessment; think of telematics in the motor insurance sector. “This will provide a far better evaluation of the enterprise cyber-hygiene and therefore the risk position of the insured,” says Mr Whitfield.

Someone who is very familiar with calculating risk exposure is Visesh Gosrani, director of risk and actuarial solution architect at Guidewire Cyence. “The cyber-risk model needs to look beyond pure technology and extend the problem to people and processes,” he says. “A holistic data-driven approach is necessary to get a complete view of the multi-faceted cyber-risk of companies.”

Given the rapidly changing environment also requires a continuous loop between data collection and risk-modelling, this represents a challenge when these are performed in silos, Mr Gosrani admits.

When it comes to specifics, the economic modelling metric must be broken down to address frequency as well as severity, financial loss and recurrence. The latter, asking if a company experiences a breach what is the probability of a follow-on event occurring, requires insight into organisational cybersecurity policy and process.

Cyber-insurance has a lower decline rate for claims than most other lines of insurance

The insurance industry must also consider performance across portfolios, so any cyber-risk model must look at the economic impact of risk accumulations, aggregate events and disaster scenarios, and then translate these into probable loss curves. Otherwise insurers would be unable to deploy capital and justify their decisions to shareholders, regulators and rating agencies. “This requires a revolutionary approach to how insurers utilise data-listening and artificial intelligence to create the right models for tracking risks that are extremely dynamic,” Mr Gosrani adds.

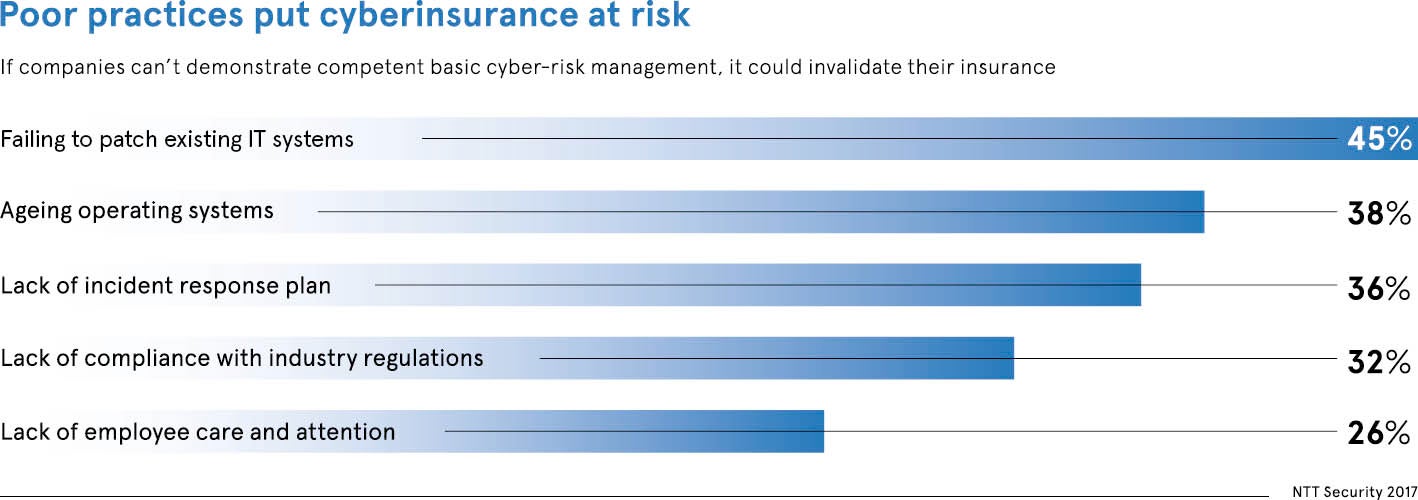

Ask most organisations about cyber-risk insurance and the lowest common denominator response will be along the lines of how likely is a pay-out if a breach occurs? Neira Jones, senior adviser for financial services with the Centre for Strategic Cyberspace and Security Science, says: “Whether a cyber-insurance policy will pay out will depend on how much businesses understand their environment, their vulnerabilities and their consequences.”

Ultimately, it’s about fostering partnerships between the organisation seeking cover and their insurance provider. “The financial services and information services industries are prone to assaults on their infrastructure such as denial of service or hacking attacks on servers, while the public sector exhibits patterns of compromise due to misuse and errors or cyber-espionage,” Ms Jones points out.

The devil, therefore, is almost always in the detail. Sjaak Schouteren, partner at global insurance broker JLT Specialty, warns that the importance of exclusions is particularly acute in the technology and cyber-arena, even down to specific aspects of software being used.

“If a company uses Windows XP on their system and suffers a breach, it may still be able to claim if the breach occurred outside of Windows XP,” Mr Schouteren explains. “If the breach occurred via a Windows XP vulnerability, there is not likely to be a rightful claim because the software itself cannot be updated, having been left behind by Microsoft.”

The good news is that it’s extremely likely a cyber-insurance claim will be paid, according to Graeme Newman, chief innovation officer at CFC Underwriting. “Cyber-insurance has a lower decline rate for claims than most other lines of insurance,” he says. “We paid more cyber-claims in 2017 than ever before and 2018 is already looking to eclipse that by a considerable amount.”