Cancer is a big enough foe on its own, but the pandemic has pitched its malignancy onto unmapped territory where even entering a hospital or clinic has become fraught with danger.

Delivering cancer care, when resources are stretched and coronavirus infection stalks contacts and procedures, has stretched healthcare providers’ ability to cope with heavy workloads and complex logistics.

Around 2.5 million people in the UK are living with a diagnosis, but staff shortages, delays caused by heightened safety protocols and the need to distance cancer patients from COVID-19 wards has caused widespread disruption across cancer care.

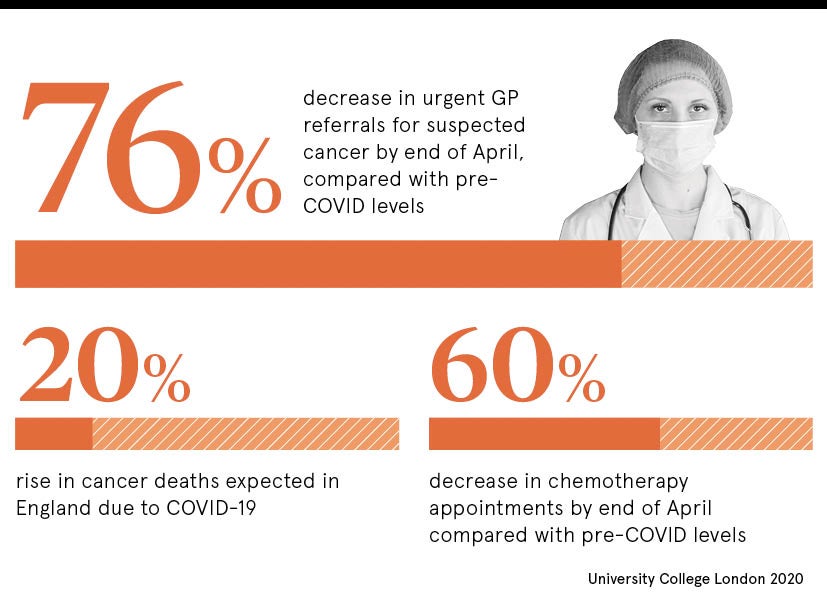

A study published during the summer forecast the UK could experience an extra 350,000 cancer deaths over the next year from postponed operations, delayed treatments and patients ignoring symptoms or delaying diagnostic appointments for fear of exposing themselves to infection risks in the health system.

Although the arm wrestle with resources and public confidence will continue for some time, healthcare providers have adapted swiftly to ensure patients receive cancer care and emotional support no matter where they are on the treatment spectrum.

Private hospitals, free from COVID-19 patients, were brought on stream, 19 regional cancer hubs were established to deliver urgent surgery, physical appointments were switched to digital platforms, medication regimes were delivered to patients’ homes and mobile wards were deployed to meet local needs.

The NHS introduced drug “swaps” to provide alternatives that could be taken at home, rather than in hospital settings, with a reduced impact on patients’ immune systems to minimise the risk of infections.

NHS response to cancer care risks

“The pandemic has had a fairly devastating impact on cancer services and people with cancer,” says Sara Bainbridge, head of policy at Macmillan Cancer Support, which offers high-impact support to 1.9 million people annually. “But we have seen an incredible response from staff and support services.”

Dr Layla McCay, director at the NHS Confederation, which represents NHS organisations and its leaders, adds: “The pressure has been intense. It is not that people have stopped getting cancer, but the impact has been at every stage from diagnostics through to care. Staff have been working amazingly hard, but that intensity is not sustainable.”

The workforce strain – healthcare staff also have to contend with a heightened risk of contracting COVID-19 – is playing out across an NHS staff shortage of 84,000 with the government-pledged cohort of 50,000 extra nurses still some distance away from the frontline.

But the response has been full of ingenuity that ranges from national alliance with private healthcare providers to run and staff the cancer hubs, to using mobile “cancer buses” that have been used as safe spaces to deliver chemotherapy to four patients at a time, achieving 60 sessions a day safely.

Home care has been ramped up at Clatterbridge Cancer Centre, on Merseyside, as the number of people receiving care at home from specialist chemotherapy nurses has increased by 15 per cent during the outbreak, with 285 patients in the area having oral chemotherapy delivered to their door by local volunteers.

COVID-19 blueprint for second surge

Bristol Haematology and Oncology Centre believes it has developed a blueprint to cope with COVID-19 during the second surge. It switched from face-to-face outpatient clinic appointments to an almost entirely telephone-based outpatient service, increased the prescription length for some oral medications, and sent some treatments to patients’ homes to avoid compromising shielding, while patients established on immunotherapy were changed to longer regimens.

“It has been fluid and has heavily relied on the dedication and goodwill of staff who have sacrificed holidays or time with their families and put themselves on the frontline to not only treat patients with coronavirus, but also to ensure oncology services have been able to continue,” according to a report from the centre.

An NHS Confederation survey revealed that 50 per cent of NHS leaders were not confident that cancer care services could recover swiftly. “Cancer services, like all other services, need to learn the lessons from COVID-19,” says McCay. “Digital innovation and new, integrated ways of working will have raised new opportunities to improve the efficiency and the effectiveness of diagnosis and treatment. But, with a second surge coming, it is vital that we have the investment to ensure it has the workforce and the physical capacity it needs.

“We also need to think creatively about how we can make the very most of what we have to give patients the best service. We need to be practical in understanding what can be achieved across what timescales to restore these services because it’s not just a matter of turning a switch and everything’s back to normal.

“This is very complex stuff and COVID-19 has really shone a light on inequalities with data showing that people who are poor or from BAME [Black, Asian and minority ethnic] communities have been disproportionately affected.”

Clear communication about changes to treatment plans or locations has been one of the most important elements of cancer care during the pandemic, Macmillan Cancer Support’s Bainbridge adds, and although virtual consultations are effective, they may not be appropriate for sensitive conversations.

The charity has launched The Forgotten C campaign to ensure the government tackles backlogs in diagnosis, treatment and care, and that future services will be based on personalised needs.

“At the start of the pandemic, the NHS was promised what it needs and it still needs that commitment because the challenge for cancer certainly isn’t finished. We need to make sure that progress made on cancer over the last few decades is not lost,” Bainbridge concludes.

Cancer is a big enough foe on its own, but the pandemic has pitched its malignancy onto unmapped territory where even entering a hospital or clinic has become fraught with danger.

Delivering cancer care, when resources are stretched and coronavirus infection stalks contacts and procedures, has stretched healthcare providers’ ability to cope with heavy workloads and complex logistics.

Around 2.5 million people in the UK are living with a diagnosis, but staff shortages, delays caused by heightened safety protocols and the need to distance cancer patients from COVID-19 wards has caused widespread disruption across cancer care.