“Work about work” is a relatively little-known term in the corporate world, but too much of it can have a big impact on employee wellbeing across organisations globally.

Such work about work consists of the bureaucratic tasks required to get the real work done and includes searching for documents, responding to emails and managing changing priorities.

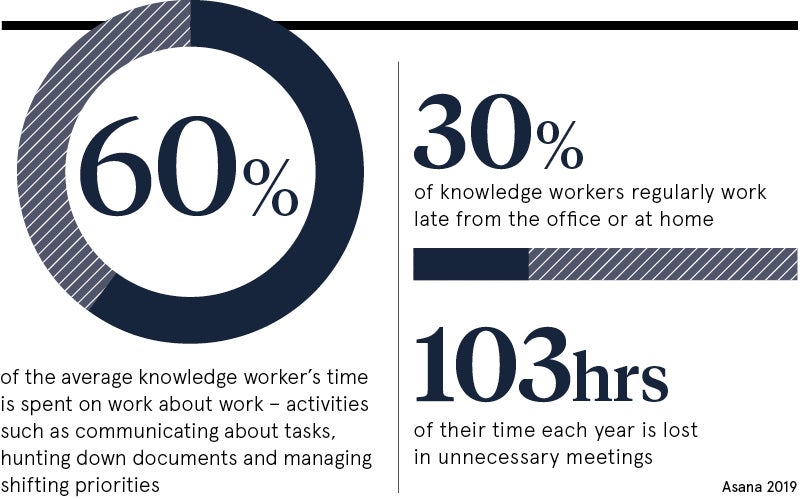

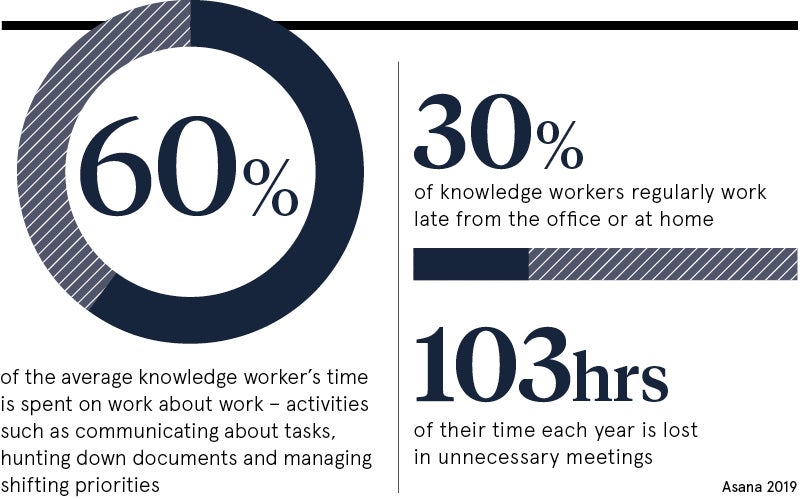

But the Anatomy of Work Index, conducted among more than 10,000 people around the world by team-based work management platform provider Asana, has revealed the average knowledge worker spends about 60 per cent of their time on mundane duties that add little real value, rather than focusing on meaningful activities to inspire and energise them.

Indeed, over the course of a year, these workers spend 103 hours in unnecessary meetings, which comprise 61 per cent of the total. A further 209 hours are lost on duplicated work and another 352 on discussing tasks.

Unsurprisingly then, only 27 per cent of the average employee’s time is dedicated to the job they were hired to do, while the remaining 13 per cent is focused on strategic planning and forward-looking analysis.

But this unintended focus on mundane tasks has a number of knock-on effects, none of which are positive. Firstly, it has a negative effect on staff productivity. Because of the volume of tasks most knowledge workers have to deal with, a huge 88 per cent acknowledge that projects have been delayed and deadlines missed as a result.

Secondly, when looking at the issue from an employee wellbeing perspective, this situation all too often means that people end up having to work long hours to keep on top of things. But such an energy-sapping scenario has inevitable repercussions on their physical and mental health, and is therefore unsustainable in the long run.

Supporting employee wellbeing

For example, a previous Asana study among 6,000 knowledge workers in Australia, America and the UK found that four out of five felt close to burnout, with an unbalanced workload being the primary source of stress for a quarter of respondents.

As Josh Zerkel, Asana’s head of global community, says: “Working on lower-value tasks that keep employees from going home or switching off naturally has an impact and can reduce engagement, motivation and happiness. The combination of feeling overworked and then wasting time on avoidable tasks creates a perfect storm for many knowledge workers, eventually resulting in burnout.”

But there are various small changes that every organisation can introduce to help boost employee wellbeing. Asana, for instance, has introduced No Meetings Wednesday to free up time for staff to focus on the work that adds real value. It also encourages managers to explore different approaches to the traditional, formal thirty-minute get-together, which includes having team members prepare for swift ten-minute brainstorms or walking meetings.

Some employers have likewise introduced policies to restrict email usage. Last year, Lidl bosses in Belgium banned all internal email transactions between 6pm and 7am to enable staff to switch off, while German car manufacturer Volkswagen has configured its servers so emails can be only sent to employees’ mobile phones during the working day and for half an hour before and after, but not during the evening or at weekends.

However, to truly enable workplace optimisation, a different approach to managing “excessive noise in the business” is required, says Sean Ramsden, chief executive of Ramsden International, a wholesale exporter of UK grocery brands. The excessive noise takes the form of people “busying themselves with lots of things that aren’t really core to what the business is about”, he says.

To tackle the issue, Ramsden recommends narrowing the organisation’s focus of attention down to between three and five priorities, which are then trickled down throughout the business.

In other words, after the company establishes its three to five priorities, directors also set theirs, which feed into the organisational ones. The same principle is then applied to department heads and individual employees to ensure everyone is focused on the firm’s core mission and purpose.

Enabling workforce optimisation

“It’s about doing a small number of things brilliantly, rather than a large number of things alright,” Ramsden explains. “If the business has too many priorities, which manifests itself in too many meetings, emails and the like, it has a real impact on its effectiveness and also on employee wellbeing as people are too thinly spread.”

But there are other important ingredients to enabling workplace optimisation and supporting employee wellbeing too, says Dr Alan Watkins, founder and chief executive of coaching and development consultancy Complete.

“Most leaders have an ‘it’ addiction in that they’re addicted to targets and metrics, and see problems as something that needs to be solved by doing,” he says. “But actually the world of doing is only one of three dimensions: there’s also how people relate to each other for example, cultural issues and values, as well as the matter of trust.”

Indeed, Watkins believes that if organisations took steps to quadruple the quality of relationships and improve trust, this would be a real game-changer as it would help unlock individuals’ true capabilities, thereby making them more efficient and effective at what they do.

According to Dr Zofia Bajorek, research fellow at the Institute for Employment Studies, the key to success is line management. In her report The squeezed middle: Why HR should be hugging and not squeezing line managers, she cites a study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Nicklas Beer.

After evaluating the activities of 1,500 line managers at small and medium-sized companies in Germany, Beer found that employees with managers in poor physical and psychological health tended to find themselves in a similar situation.

As a result, Bajorek concludes that for those organisations keen to go down the workforce optimisation route: “Equipping line managers with the skills to cope with their stress and workload is important for improving the productivity and wellbeing of the employees who report to them too.”

Supporting employee wellbeing