1. No hierarchy

When app company Blinkist, whose technology distils the content of weighty academic tomes into short, 15-minute bite-sized reads, started growing rapidly during 2016 and 2017, its chief executive and founder Holger Seim noticed that holacracy, a system of self-organisation where hierarchy is non-existent, seemed to be the latest management trend.

Lauded by the likes of Zappos, the Amazon-owned shoe brand, it seemed to be the perfect answer for creating more distributed leadership.

“We started implementing it when we reached 20 people because it seemed to allow what we wanted: empowerment of teams,” says Mr Seim. Very quickly though, he realised it was a big mistake.

“By the time we’d gotten to 35 people, it simply wasn’t working,” he concedes. “People just didn’t seem to understand it. There were at least ten different versions of what people thought it was.

“When discussing new business opportunities, we found all people were doing was discussing how we could fit that around the model, rather than the opportunity itself. It was a distraction.”

Since pulling the system, Mr Seim has instead created a series of “circle teams” where everyone can still be empowered, but in a more controlled structure and with line-manager oversight. Now the business is 100 people, he says it was the right choice.

“We believe in leadership, but not micro-management, and I think we’ve reached a compromise position,” he says.

“It’s working way better. We’ve exceeded our business goals and key performance indicators; people are proud to work for us and they also feel heard.”

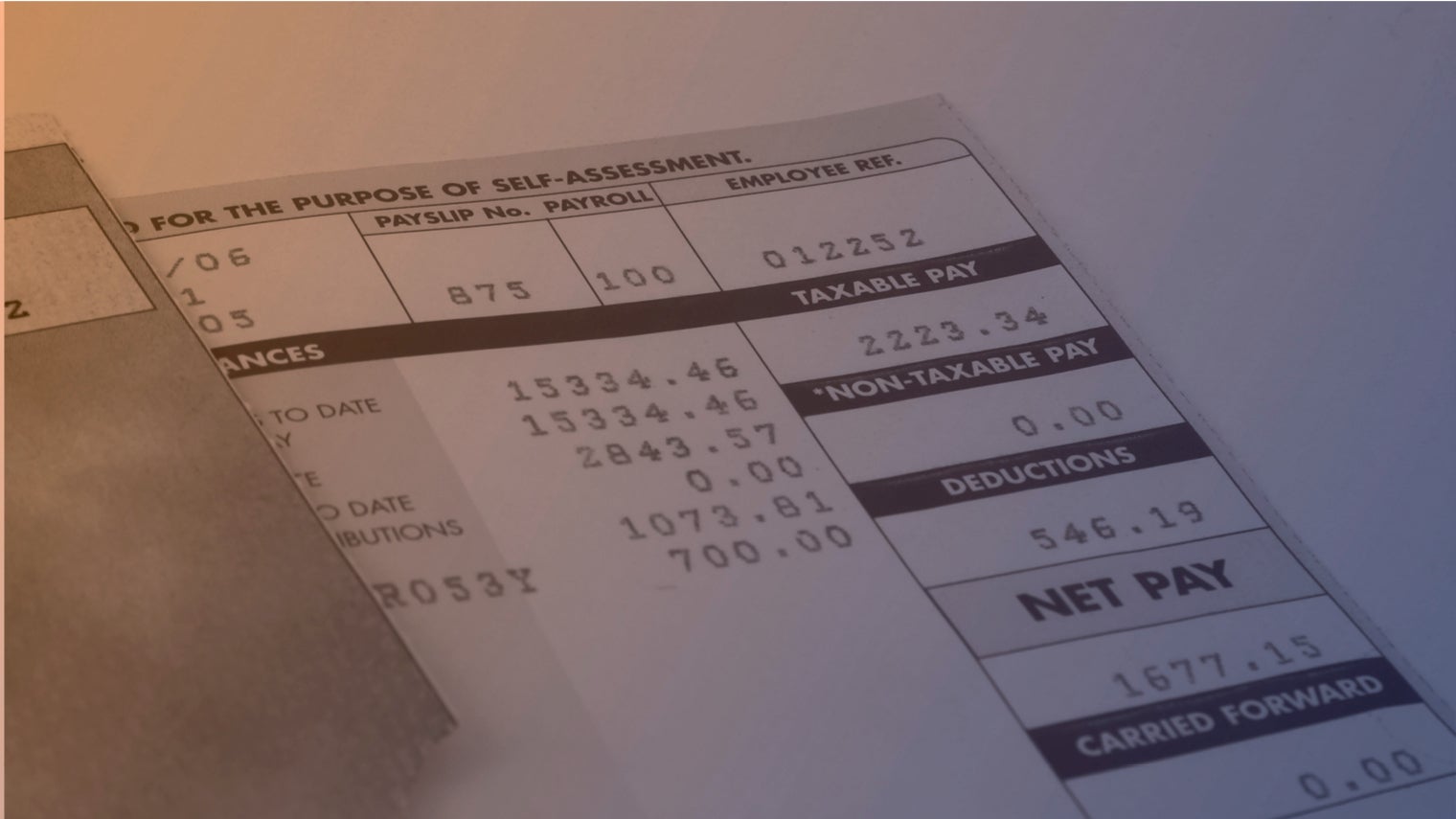

2. Pay transparency

Flamboyant British businessman Charlie Mullins, founder of Pimlico Plumbers, almost invented the recent trend for “going transparent” about pay, long before gender pay gap reporting was in the news.

Volunteering for Channel 4’s Show Me The Money to film the experiment back in 2012, the series highlighted the initially disastrous impact it had, including angry scenes where staff saw perceived injustices in pay.

“It was pretty shocking,” he says. “There were big discrepancies. Some people were taking home less or more than others, even though they were doing exactly the same job. The fur started flying.

“There was a lot of bitterness, including people demanding pay rises. I was made out to be a villain because of what I paid myself, even though I’d started the company and made it what it was through years of toil and sweat, worry and risk.”

Reflecting on it now though, he says, eventually he was glad he did it. Although, he says, firms need to be aware of fallout and be aware transparency need not necessarily mean equal pay.

“We didn’t have a structure in place; pay was messy,” he admits. “When we introduced pay transparency, yes, we lost a few people, but some actually got pay rises, while others realised just what a good deal they were already on.

“I would definitely say it’s made us more gender balanced because staff can clearly see that everyone is on a level playing field, regardless of their sex. Our pay rises are set each May – this year it’s 3 per cent across the board – and now that we have a proper structure, it means we’re not bogged down, week in week out, with people talking about pay behind everyone’s backs.”

3. Unlimited holiday

It was partly the sheer struggle of booking her two-week honeymoon at a previous employer, such that she had to work alone during Christmas and New Year to “make up for it”, and part being aware of the perk from the press, that convinced Claire Crompton of the need to introduce unlimited holiday when she co-founded her own business, boutique marketing agency The Audit Lab, in 2017.

“Unlimited holiday naturally seemed like a way we could differentiate ourselves,” she says. But while it might be successful now – it has reduced official sickness days by 34 per cent – it wasn’t always the case.

“We’ve definitely had to evolve it,” says Ms Crompton. “Initially there was an element of using it when people were actually hung-over or wanted a duvet day. Also, people initially took days off at very short notice, leaving others to have to cover for them.

“So we instituted a policy where staff have to give at least a week’s notice for holiday. We will also crack down on people if they book two weeks off every few months, for example.

“Another caveat we’ve developed is to insist people are ‘available’, that is check their phones for emails either at the start or end of the day, while off. While we’re respectful of not bombarding staff with requests we can’t handle ourselves, at the same time we expect any urgent matters only they can deal with to be looked at.”

According to Ms Crompton, the policy gets real employee buy-in, but she cautions it can be seen as an attractive of-the-moment perk which needs proper thought.

“We’re less than ten people, so it works at the moment, but I expect we’ll probably need to revisit it as we get larger. As a business, our priority is to not only keep the employees happy, but also our clients as well, and there’s nothing worse for a client than their main point of contact never being in.”

1. No hierarchy

2. Pay transparency