It’s nigh on impossible to get hold of David Graeber. The anthropologist from the London School of Economics is very busy. He’s landed a bombshell of a book on the desks of business leaders, saying that many in employment do “bullshit” jobs, roles so utterly pointless that even employees cannot justify them, and now with a potential epidemic of meaningless work, something needs to be done.

“From the Daily Mail to the Bank of England, they’ve all taken notice,” says Professor Graeber, an American now between book talks in Amsterdam. It resonates widely because many people secretly believe it’s true, even if they don’t admit it. “The big question I have is why isn’t anyone doing anything about it?” he asks.

Certainly, all of us know what unproductive work looks like, dealing with an email inbox after a week’s holiday is a good benchmark, only to realise 90 per cent was superfluous rubbish anyway.

Watch W1A, the British satire of the BBC, to see it in its extreme or listen to frontline doctors, nurses or teachers recount the endless bureaucracy they deal with, generated in their minds by people doing pointless jobs; the endless middle managers riddled with self-importance and made-up titles.

Millions worldwide not doing meaningful work

Professor Graeber emphasises this with a tantalising quote from President Barack Obama’s objection to expanding US Medicare, which could slash paperwork and administration: “That represents one million, two million, three million jobs filled by people who are working at Blue Cross, Blue Shield or Kaiser, or other places. What are we doing with them? Where are we employing them?”

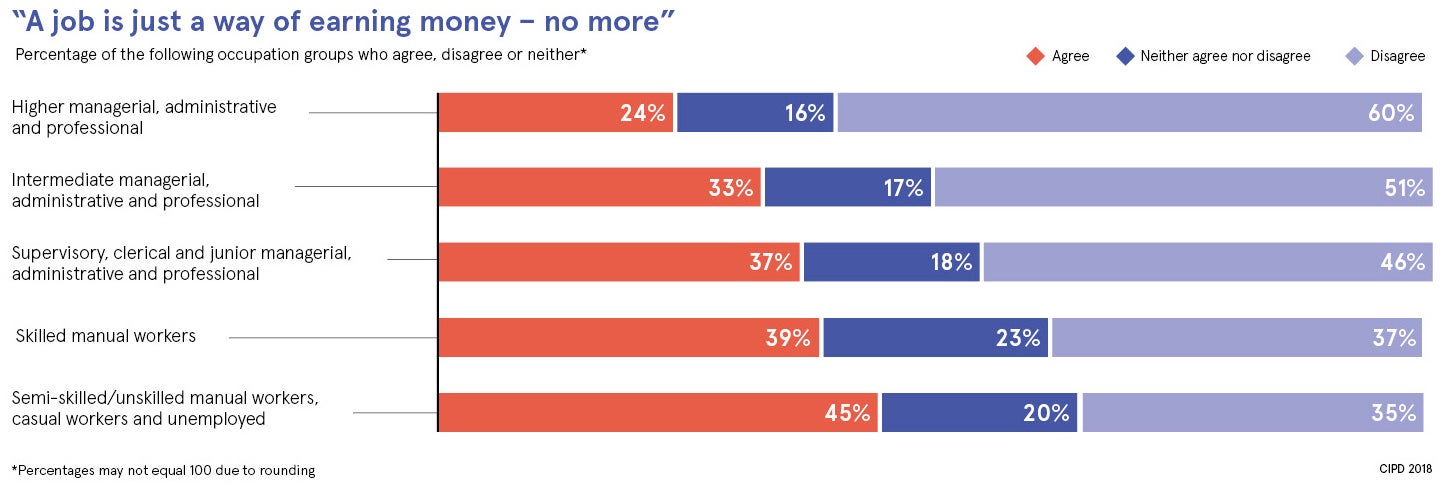

There are few statistics on unfulfilling jobs. But in a YouGov poll, UK workers were asked “if their job made a meaningful contribution to the world”; 37 per cent said no and in a similar survey 40 per cent of Dutch employees said their job had no reason to exist.

In Professor Graeber’s new book Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, he postulates that more than half the jobs that exist are pointless and are in fact toxic to society.

In the United States, 21 million people are estimated to be creating little or no economic value, according to a study by Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini. Reassigning them in more productive roles could give the economy a $3-trillion boost, they claim.

“Most of the jobs people do are not productive and many people are miserable at work. There is a perverse morality going on. Many believe we should suffer nine to five and not enjoy working. There’s also an inverse relationship between work and money. The more people get paid, the more they should suffer,” explains Professor Graeber.

Pointless work could be draining our productivity

When Rolls-Royce recently axed an eye-watering 4,000-plus jobs, slashing its middle managers and support roles for a leaner, simpler business, some argued that they were cutting back on meaningless jobs. The company, known for its bureaucratic processes, is still in good health we’re told. In fact, the stock market rewarded the cull with a six-month spike in share prices.

The chief executive of the company is probably cursing economist John Maynard Keynes. He said in the 1930s that over time, machines and technology would allow people to be more productive, not less. This was his argument for a 15-hour working week, which just hasn’t materialised.

Tapping on our keyboards, filling out endless schedules, spreadsheets and PowerPoint slides may have sucked the productive life out of us, enabling an ever-greater division of labour, managerial control and complex structures. With many of the world’s largest economies in a prolonged productivity slump, there are lessons to be learnt.

“Many people only do 15 hours of productive, meaningful work a week anyway; work reduction may be a good thing, it would make people focus,” says Professor Graeber. “Digitalisation and the latest technology have actually had the opposite effect in some sectors; productivity has gone down, especially in the teaching and caring professions.”

Workers looking to do meaningful work

There’s also still an obsession in corporations that many jobs should be full time, with bums on seats and employees at least looking like they’re busy and creating value, even if they aren’t doing any meaningful work. Yet, aided by our tech-driven PC systems, work can feed off itself, creating more work. Professor Graeber calls this vicious cycle of work for work’s sake the “Sovietisation of capitalism”.

Tom Goodwin, head of innovation at Zenith Media and author of Digital Darwinism, adds: “I’ve seen it. In many big corporations, big opportunities will require big budgets. Anything with big budgets will need a large workforce, large tender bids, large advertising campaigns, large legal challenges, all attracting vast numbers of staff because it’s important. Yet most people just get in each other’s way; it can be meaningless and unproductive.”

It doesn’t help that most people who turn up to the office on a Monday morning want to do meaningful work. They want to be useful and contribute to society. It means employees are good at sniffing out tasks that create meaning, even though they may be meaningless for the corporate bottom line.

Professor Graeber offers a radical solution: a universal basic income enabling people to do meaningful work without economic constraint, while being paid to do it. “A lot of workers want to drop out of the system. But the legal, tax and social structure of our society makes it difficult. Many are already doing part-time, freelance or their own startup so they don’t have to do bullshit jobs,” he says.

Creating meaning in each and every job

Business leaders need to ask more questions, particularly is the work their employees do both meaningful to the company and to employees themselves? The recent Taylor Review, commissioned by the government, on working practices highlights a need for self-actualisation.

“The real role for businesses is to try to create conditions in which people find meaning in their work, by not taking employees for granted, by treating them unfairly or giving them pointless work, and instead to help employees understand the purpose of the organisation in which they work and how it contributes to society,” explains Professor Adrian Madden from the University of Greenwich’s Business School, who along with Professor Katie Bailey from Kings College London has researched meaningful work.

Employee ownership structures could be one answer. The so-called John Lewis model offers a way of stimulating employees’ sense of control and dignity, and in the process flush out meaningless work. People question unproductive tasks when they are in control. It’s been adopted by more than 300 British companies.

People question unproductive tasks when they are in control

Guy Singh-Watson, founder of Riverford Organic Farmers, which distributes organic vegetable boxes UK-wide, thinks it’s a good idea, recently handing the business over to its 650 employees.

“Most people are better, more generous, less greedy and more willing to work collectively for shared goals,” he says. “As I learnt in my early days, if you paid people by the sack to fill up carrots, don’t be surprised if you find that the sack is full of stones and mud at the bottom because actually you’re just rewarding them for filling up sacks.

“If you involve them in the business and share profits, people aren’t going to put stones and mud in the bottom, so I guess in very simplistic terms that’s what we’re trying to achieve.”

Millions worldwide not doing meaningful work

Pointless work could be draining our productivity