The internet of things (IoT) has huge potential. According to one forecast, there will be a trillion connected computers in the world by 2035, built into everything from cars to toasters. Collectively, such IoT devices, which record, monitor and communicate data, herald what some call the “second phase of the internet”.

Companies at the forefront of IoT are set to be the winners of the future. But we have yet to see what industries and uses will benefit the most. In many cases, IoT projects might take years, and even decades, to come to fruition. At the same time, the decisions of executive managers are increasingly shaped by short-term concerns.

Given that IoT projects involve significant funding, a meaningful return on investment (RoI) is crucial. So how long should it take for companies to see an IoT RoI? Does this vary across industries? And how can we ensure the long-term thinking needed for IoT projects is not hampered by managers’ egos and short-termism?

How long can IoT ROI take?

IoT projects can take many forms from optimising the performance of equipment on the factory floor, to utilising workspaces more efficiently and improving patient health through wearable technology. “I’ve observed a few cases of successful IoT application to improve production processes,” says Vitali Kalesnik, director of research for Europe at Research Affiliates. Multiple sensors are placed around the production line to provide engineers with real-time information, collect data and then apply machine-learning algorithms to improve production.

“What is interesting about IoT is how quickly you can see RoI,” says Jon Forster, manager of the investment trust Impax Environmental Markets. “For instance, industrial companies often adopt software to make their operations more efficient and, indeed, tend to see RoI pretty much from day one; reduced labour costs, the benefits of predictive maintenance, for example.”

If managers’ evaluation and pay are short term in nature, they tend to favour short-term payoff

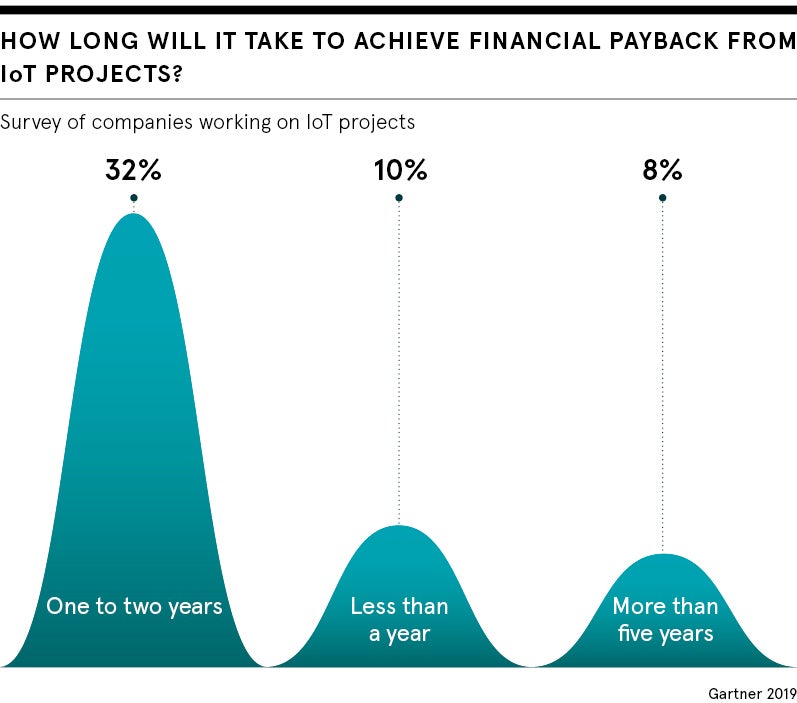

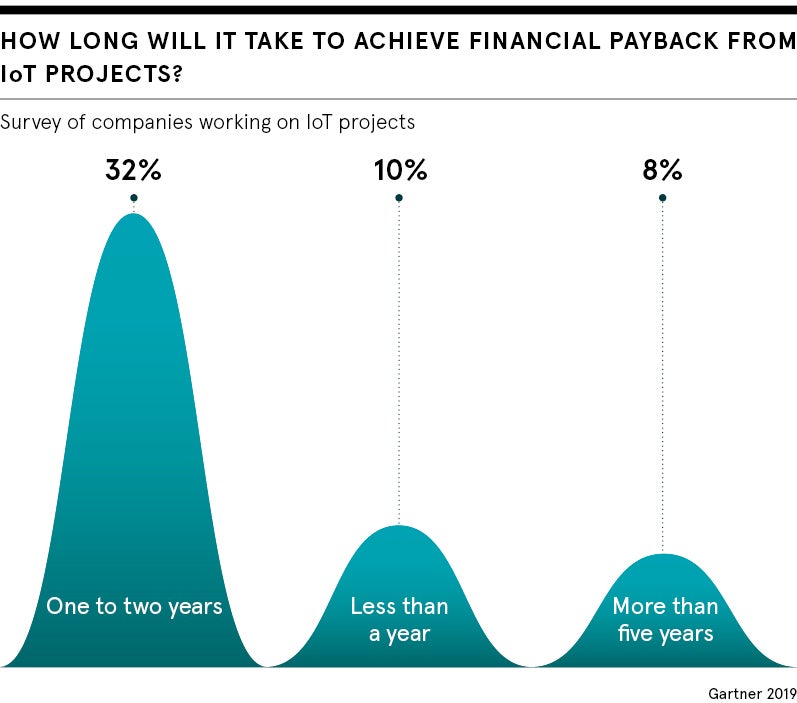

But while some industries might benefit straightaway, others need more patience. So how long does it take for IoT RoI to pay off across a variety of industries? Three years, on average, according to Gartner’s 2019 IoT Implementation Trends Survey, which included 501 companies working on IoT projects. Some 32 per cent of companies estimate they would achieve financial payback for their IoT projects in one to two years, with 10 per cent estimating this would take less than a year. Only 8 per cent estimate they would have to wait for more than five years.

At the same time, we have yet to see the full potential of IoT. Kalesnik compares the evolution of IoT to the introduction of Internet companies in the nineties. “If we were to invest in search businesses back in the late-nineties, we would probably choose Yahoo! and AltaVista. Of course, today we know that Google, which was a really geeky company at the time, is the winner,” he says.

Although the potential of online search businesses was obvious from the onset, it was really difficult to forecast which particular business would win. In the same vein, it’s yet unknown which technologies, companies and applications will benefit from IoT the most.

IoT ROI versus manager ego

As IoT continues to evolve, some projects might take years and decades to develop. What happens if RoI on IoT projects is only expected once a manager has left the role? Does this impact the decision-making process?

After all, managers may not have the company’s best interests at heart, if their egos interfere. They might choose to invest in projects that make money in the short term, within their tenure, even if potential IoT projects could bring more value to the company in the long run.

“If managers’ evaluation and pay are short term in nature, they tend to favour decisions which favour short-term payoff over the long term,” says Kalesnik. Research has shown that executives tend to sacrifice the long-term value of companies to meet short-term earnings targets.

In a 2017 study, researchers Alex Edmans, Vivian W. Fang and Katharina A. Lewellen found that stock options used as executive incentives tend to make management sensitive to short-term stock performance. They found such focus on short-term performance leads to reduced research and development, and investment.

So what can be done to counter this tendency? Kalesnik suggests a longer investing period for management stocks of about three to five years to ensure managers have incentives to look after the long-term value of the company. What’s more, he points out that startups, where managers’ profits tend to be tied up with the equity they own for a long time, naturally align with the long-term thinking needed for IoT projects.

For companies to succeed with IoT, the right managerial incentives are key. After all, the second phase of the internet promises to be a long game.

How long can IoT ROI take?

IoT ROI versus manager ego