Scientific data clearly indicates that employee engagement drives organisational profitability; nonetheless, only a minority of employees in most organisations are engaged. Indeed, the evidence suggests that disengagement is not just the norm, but a worldwide epidemic.

Global surveys show that many employees dislike their jobs.i LinkedIn and other recruitment firms estimate that 70 per cent of the workforce consists of passive jobseekers – people who are not actively looking for jobs, yet still hopeful for better alternatives. In the realm of relationships, this would equate to 70 per cent of married people being open to replacing their spouse.

Moreover, even in economies with low unemployment such as the UK, many people are ditching traditional employment to start their own business. And while an increase in entrepreneurial activity has collective benefits, most startups fail and the majority of people who switch from traditional to self-employment end up working more to earn less.

Clearly, then, disengagement is a problem, but why are so many employees disengaged? Scientific studies highlight two main reasons. First, organisations don’t understand what people really want from work. And second, a substantial proportion of existing managers are incompetent leaders.

To motivate employees, organisations must learn to decode their individual values and needs at a granular level

David Sirota, a pioneer of engagement research, notes that employees hope to fulfil three major needs at work. The first is a need for achievement – they are satisfied when they are given important and challenging work, and their work is recognised. The second is a need for camaraderie, met when people are able to build relationships and bond with others. The third is a need for equity, fulfilled when people think they are treated fairly.

It follows that employees will be more engaged if their accomplishments are valued by the organisation, if they can form meaningful relationships with their colleagues, and if the rules of conduct are transparent and enforced fairly. Conversely, if they feel unappreciated, isolated or treated unfairly, they will become disengaged, alienated and burnt out.

While these needs are universal, different people may value some more than others and these individual differences have salient career implications. For example, when employees value camaraderie over achievement, they will prioritise getting along over getting ahead. And when they care more about achievement than equity, they will tolerate unfairness as long as they can attain status.

Furthermore, the same needs may be expressed in different terms. Indeed, some people may fulfil their need for achievement through financial rewards, while others may define it in terms of recognition – promotions, publicity and fancy job titles, for example. Likewise, some employees may fulfil their need for camaraderie by helping their colleagues – expressing an altruistic need – whereas others may do this by partying with them – expressing a need for hedonism. Clearly, one size does not fit all. To motivate employees, organisations must learn to decode their individual values and needs at a granular level.

Although leaders own the job of engaging employees, they are generally ill-prepared for the task. One reason is that the wrong people are often promoted into leadership positions. Among wrong people are those who perform well as individual contributors because of their technical expertise, but lack the necessary people skills to manage teams; people who are politically savvy and good at managing upwards, but too greedy to attend to their subordinates’ wellbeing; and people who are good at faking competence, for instance seeming confident and/or taking credit for others’ achievements, but are actually talentless.

A second reason many leaders are unable to create engagement is that leadership development programmes tend to help those who need it the least. Humble and self-critical leaders typically sign up for training and coaching sessions, while arrogant and self-deceived bullies are prisoners of their own self-belief.

Leading organisational psychologists, such as Robert Hogan, estimate the baseline for managerial incompetence is at least 50 per cent and that may be a conservative estimate. You need only to google “my boss is…”, “my manager is…” or “my supervisor is…” and read the most popular auto-completion options to understand how most people regard their leaders. Unsurprisingly, research shows that most people quit their jobs because of their bosses and around 35 per cent of the variability in team engagement levels can be attributed to leaders.

Leading organisational psychologists, such as Robert Hogan, estimate the baseline for managerial incompetence is at least 50 per cent and that may be a conservative estimate. You need only to google “my boss is…”, “my manager is…” or “my supervisor is…” and read the most popular auto-completion options to understand how most people regard their leaders. Unsurprisingly, research shows that most people quit their jobs because of their bosses and around 35 per cent of the variability in team engagement levels can be attributed to leaders.

In order to fix their engagement problems, organisations should start by selecting and developing better leaders. Contrary to popular belief, the most engaging leaders are not confident and flamboyant like Donald Trump. They are modest, self-aware and empathic, meaning they have emotional intelligence. They fly under the radar, while helping their teams perform. They are trustworthy and understand their limitations. In other words, the most engaging leaders are rather boring – think German Chancellor Angela Merkel or Apple’s Tim Cook rather than Tony Blair or Steve Jobs.

More importantly, whatever their own value orientation, leaders must understand what motivates their employees. To develop leaders largely requires enhancing their emotional intelligence so they can improve their ability to understand people.

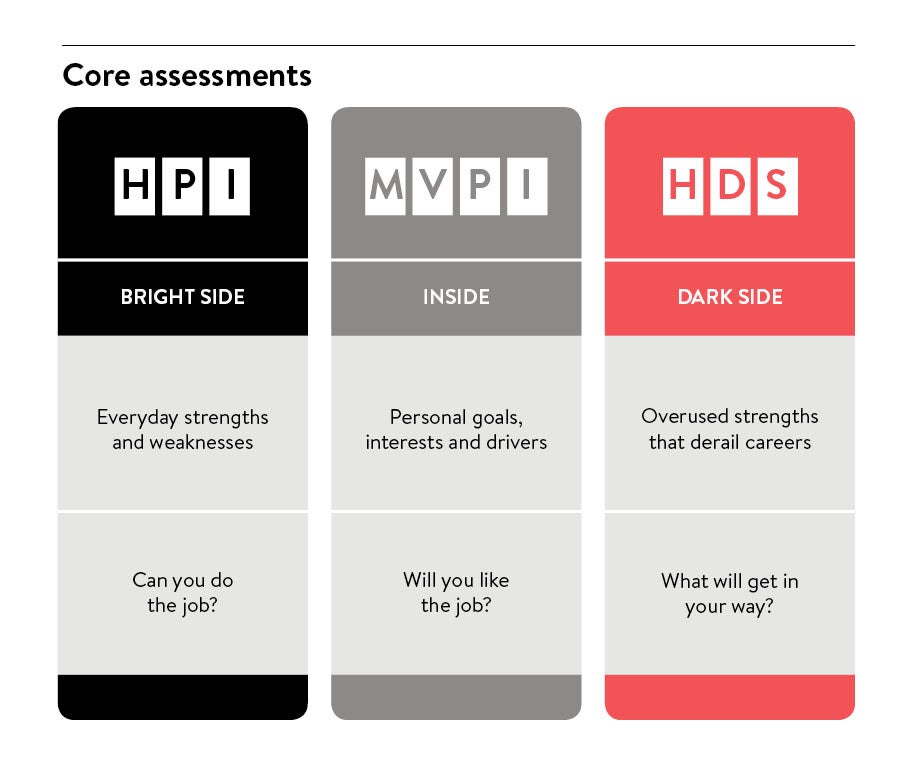

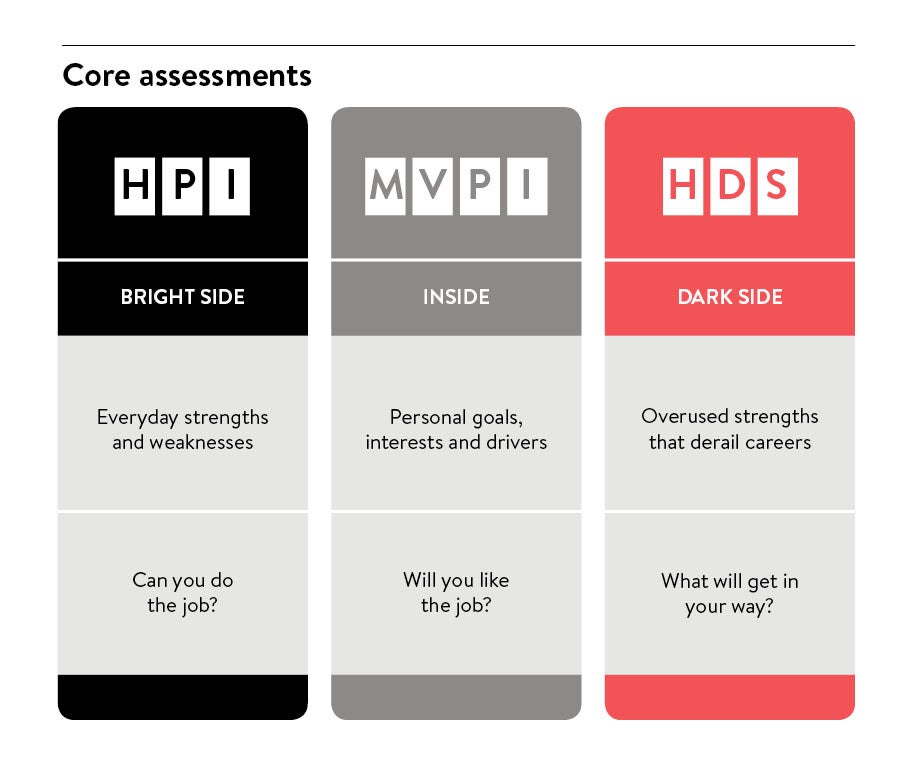

At Hogan Assessments, we create scientifically defensible personality assessments to profile leaders and their teams. Our assessments don’t just predict performance – they also explain it. When leaders and teams go through them, they receive valuable information about their style, values and limitations. This information can help leaders create engagement and, in turn, be more effective at work.

Over the past 30 years, we have assessed more than five million leaders and employees in more than 400 jobs and 50 countries. Our tools are used by two thirds of Fortune 500 companies, as well as thousands of small businesses, to select and develop employees and leaders. You can think of us as the arms manufacturers in the war for talent – we create the “weapons” that help organisations attract the right people and develop their full potential, particularly by teaching them how to behave better.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic is professor of business psychology at University College London, chief executive of Hogan Assessments and a visiting professor at Columbia University, New York

i Pfeffer, J. (2016). Leadership BS: Fixing workplaces and careers one truth at the time. Harper Business