If you look at the profile of senior leadership in publicly listed companies, the picture is predominantly of men in their 50s and 60s, a generation defined as baby boomers.

The Norman Broadbent 2014 Board Review of 1,700 quoted companies found that chairman and non-executive directors tend to be in their 60s. However, in ten to fifteen years’ time, many of the top positions will be occupied by millennials, those born between the early-80s to early-2000s. In fact, in some tech and startup businesses, millennials such as Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg already occupy leadership positions.

The dominance of the old-school chief executive is on the wane, predicts Jonathan Hime, group managing partner at leadership advisory firm Marlin Hawk. “Boardrooms will look very different in five years’ time as the millennials rise through the ranks and challenge the management culture in many organisations,” he says.

Paying attention

Why does the march of the millennials matter? Deloitte estimate millennials will comprise 75 per cent of the global workforce by 2025, so it’s critical firms get to grips with the talent management of this generational cohort. In the UK, millennials currently form 35 per cent of the UK workforce and this figure can only increase.

Organisations ignore the development of millennials in their workplace at their peril, warns Dimple Agarwal, a partner at Deloitte. “In most global companies, 40 to 50 per cent of their workforce are millennials. If you’re not taking care of a big chunk of your workforce now, then you’re already behind your competitors,” she says.

“It’s a big cultural shift as people in the top positions in large, consumer businesses are not millennials, but if you look at the technology and startup sector, then millennials are already in leadership positions.”

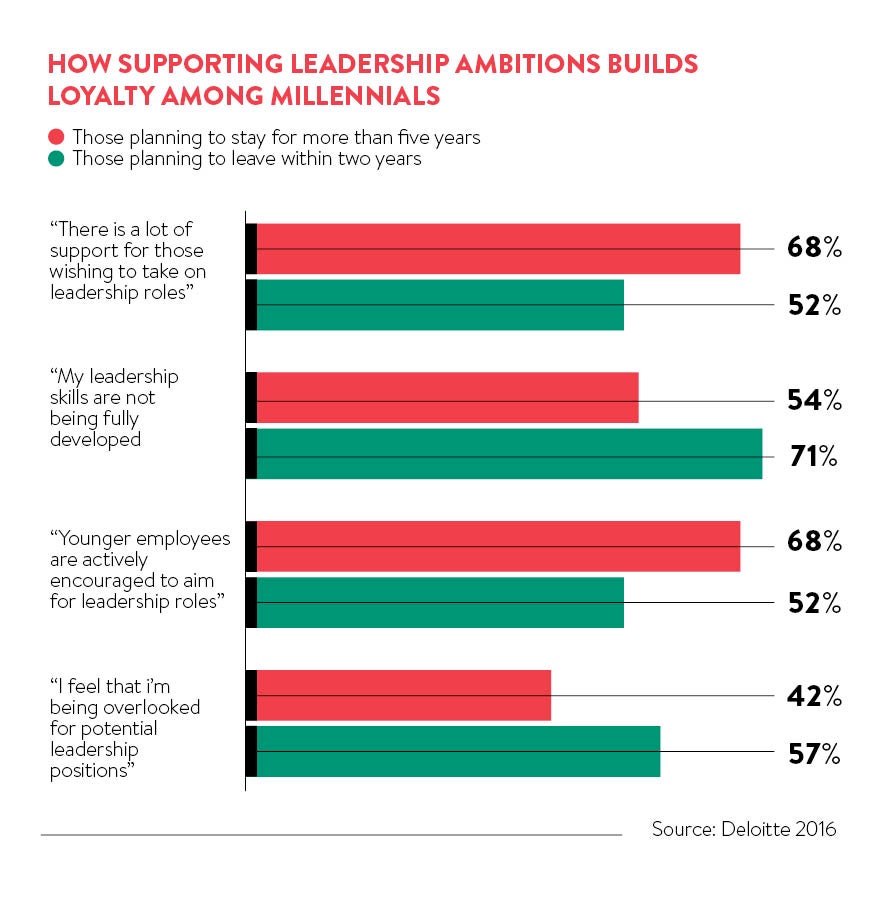

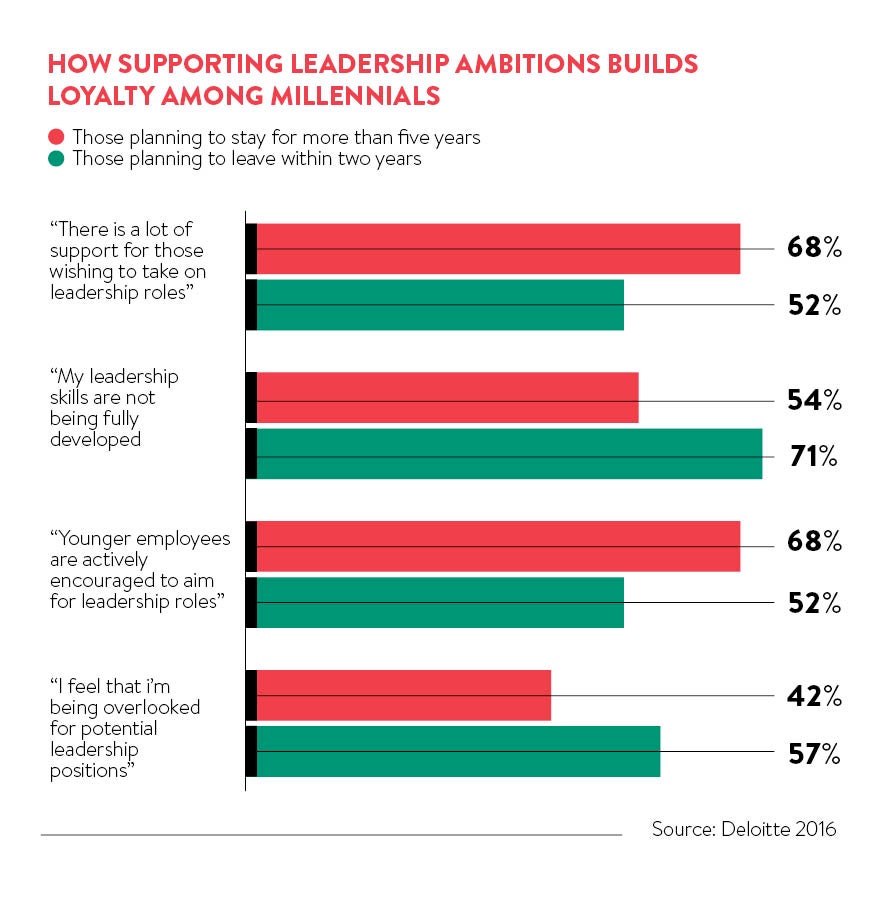

The 2016 Deloitte Millennial Survey of 7,700 millennials in full-time employment and drawn from 29 countries found that nearly two-thirds of millennials say their leadership skills are not being fully developed. This was despite the fact that millennials believed business placed the highest value on leadership as a skill in a 2015 Deloitte survey. “There is a big gap in expectations with millennials believing that organisations are not investing enough in them,” says Ms Agarwal.

A lot of organisations will spend large sums of money on leadership development, but it’s usually targeted at the top two to three layers of the organisation. She says: “Organisations aren’t investing across the whole workforce, which is why they need to redirect their investment.”

The 2016 Deloitte survey also reveals that the millennial generation aren’t particularly loyal to their employer as two in three millennials expect to leave their organisation by 2020. This presents a big talent management challenge for organisations striving to retain a large segment of their workforce.

Millennials change jobs more frequently than previous generations, says Sue Honoré, associate research consultant at Ashridge Executive Education. “Therefore, they are constantly seeking interesting and challenging work, and have less patience for drudgery. They value coaching and mentoring highly, and expect those more experienced people around them to provide that freely,” says Dr Honoré.

Managing millennials

But what type of development do millennials crave in the workplace, particularly for leadership roles? Ms Agarwal says: “There may be parts of the organisation that are not convinced they have the experience, but it’s about taking risks. It’s about creating opportunities to give them leadership roles early on and skills, such as how to manage senior stakeholders and how to develop your ability to envisage where the business is going.”

This generation is nomadic, and open to working and living abroad, says Mr Hime. “They want exposure to new cultures and geographies. This will be a leader who wants to be truly cross-cultural and embed themselves into a different environment, so their style is much more global,” he says.

Leadership development needs to change not just due to the expectations of the millennial generation, but as a result of the volatile economic conditions in which businesses operate

Another factor that distinguishes millennials from other generations is their preference for technology, says Ksenia Zheltoukhova, research adviser for the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. “They want to access information quickly and want more real-time feedback, so organisations need to develop learning on the job rather than going on a course,” she says.

The development of millennials needs to resonate with them and not just be linked to financial performance, Omid Aschari, professor of strategic management at the Institute of Management, University of St Gallen, in Switzerland, observes. “They don’t buy into the fairy tale that as long as the balance sheet is fine, direct and indirect stakeholders benefit as well,” he says. “Millennials are more sensitive to the way the organisations assume responsibility beyond its own wellbeing. They want to see the wider impact on society and the wider environment.”

However, it’s important not to push away other generations by catering solely to the needs of your millennial workforce, warns Nicola McQueen, managing director of Capita Resourcing. “One size does not fit all,” she says. “While they may require a different approach, it’s important not to alienate other generations in the business and instead use millennials as agents for change in the leadership development process. Talent identification programmes should be mapped across all generations in the business in order to be effective.”

‘Mindful’ leadership

Leadership development needs to change not just due to the expectations of the millennial generation, but as a result of the volatile economic conditions in which businesses operate, says Dr Bernd Vogel, associate professor of leadership and organisational behaviour at Henley Business School. “It’s about more stretch assignments and on-the-job learning especially if you have a business environment that is ambiguous and volatile,” he says.

The rapid pace of change in the business world will mean that millennial leaders, in fact any business leader, will have to be adaptable and inclusive, argues Ms Agarwal. “One of the crucial leadership qualities needed by future leaders will be the ability to embrace different cultures and diversity of thinking, and the ability to change.”

The millennial generation is all about “mindful” leadership with a focus on values, conduct and people, says Mr Hime. “They thrive on building and motivating teams. They want to develop themselves and their colleagues. They are constructive agitators, with a remarkable ability to achieve goals in a shifting environment.”

Ms Zheltoukhova believes that millennial leaders will be interested in a wide range of outcomes from leadership, not purely financial. “Millennials are much more inclusive in their approach and they’re not just thinking about the bottom-line outcomes, but the social outcomes as well,” she says.

This preference for ethical leadership is reflected in the 2016 Deloitte Millennial Survey which found that 87 per cent of millennials believe that the success of a business should be measured in terms of more than just its financial performance.

Millennial leaders will be highly networked and far more entrepreneurial, Dr Honoré predicts. “They will look for personal value in any role and probably switch loyalties quickly if they feel they are not gaining from their work,” she says. “They may be less skilled at face-to-face people skills and the communication of tough messages, which may impact their effectiveness as leaders. However, the best of this generation will be very successful and exploit the skills they have developed in their lives, and pick up those they may have missed out on compared to previous generations.”

One of the challenges facing millennial leaders is that there will be multiple generations in a workplace, Ms Agarwal points out. She says: “Leaders will have to be adaptable and inclusive as they will have to deal with four generations in the workplace. A lot of older workers are rejoining the workforce, and organisations need to think about multiple ways of delivering learning and development as it’s not just about developing the millennial generation.”

Mr Hime believes that the emergence of millennial leaders will challenge organisations’ talent management practices. “Organisations will need to adapt to the emergence of these millennial leaders otherwise they will struggle to pass on the baton,” he says. “Some boards already look and feel completely renewed. Others have recognised the need for change and are taking action. The ego-obsessed, hierarchical boards of old are simply not suited to the post-recession culture of businesses today.”

CASE STUDY: PwC

PwC, the largest professional services firm in the world and one of the big four auditors, employs some 20,000 people in the UK of whom 66 per cent are millennials.

“We know that our millennials want to be invested in, and their development needs to be relevant and personalised for them,” says Louise Brownhill, PwC’s chief learning officer. “There is a big increase in gamification and mobile learning, and we know our millennial population want to learn on the go.”

As a result, PwC has developed an online game, to be launched in April, for its employees to be able to experiment with their leadership style and approach within a simulated environment. “We’ve developed project management simulation to allow our learners to be project management leaders and the simulation provides feedback relevant to the learner,” says Ms Brownhill.

PwC is investing in leadership capability at an early point in the millennial’s career as this reflects the complexity and pace of change that people will have to deal with at all levels of the organisation.

Ms Brownhill adds: “The technical skills within professional services are critical, but we’re also focusing on softer skills such as leadership.”

This year, the firm developed an 18-month leadership programme for its newly promoted staff to provide them with a strong foundation in leadership skills and help millennials pro-actively plan their careers.

“Part of the emphasis is on our people building broader networks and also focusing on developing their own resilience, which is increasingly an issue because of the complex world we live in,” Ms Brownhill concludes.

Paying attention