Productivity is a word more resonant of the steam age than today’s service-based economy, yet as a key driver of financial success, the measurement of output per employee continues to loom large in the business lexicon.

By pursuing progressive people management policies that allow staff to thrive, engagement and productivity tend to rise

While there can be no doubt that the UK works harder than its competitors in terms of sheer hours, whether the country works smart enough is quite another matter.

Reason for low productivity is a lack of engagement with our work

So says Tony Danker, chief executive of Be the Business, set up by Theresa May’s government at the end of 2017 to boost a historically disappointing national productivity record.

Mr Danker believes that the relationship we have with our work and therefore our willingness to go the extra mile for our employer is far more complex than mere numbers would suggest.

“Productivity is a word used by economists and outside the manufacturing arena, it really doesn’t have any emotional resonance for people,” he says. “The real issue behind the UK’s poor productivity record is lack of engagement and once we accept that fact, a host of contributory factors can be brought into play.”

Mr Danker says that when an employee complains about it being “difficult to get things done around here”, whether through lack of personal autonomy or slow decision-making further up the chain, they are “simply expressing the very human desire to get more value and meaning” out of work.

“Wanting to achieve more in your job is the same thing as being more productive, even though it is expressed in a direct, very human way,” he adds.

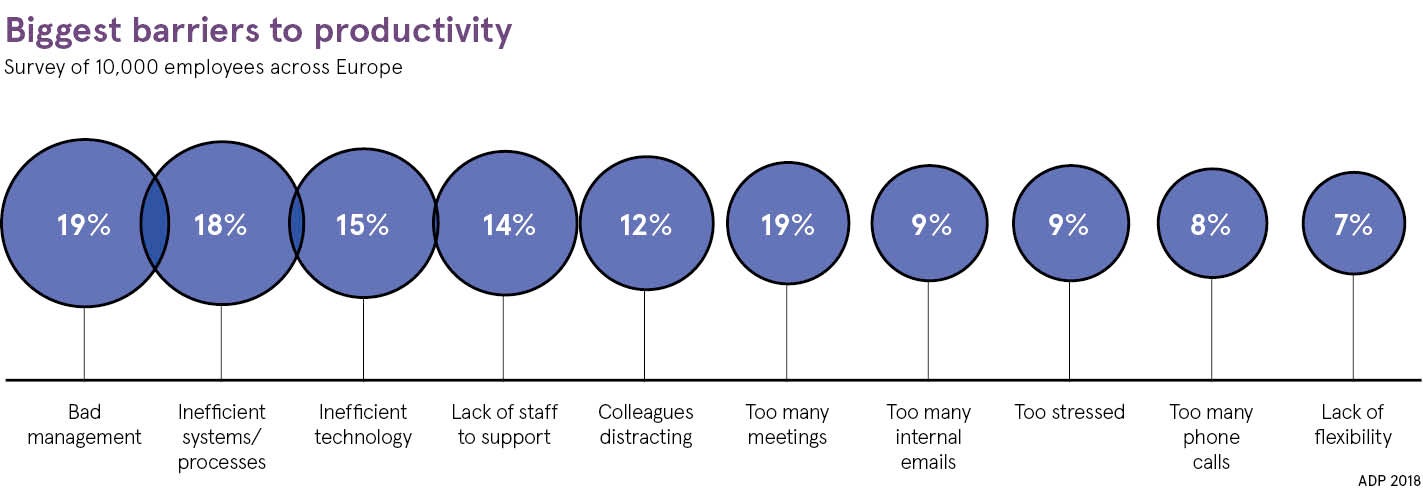

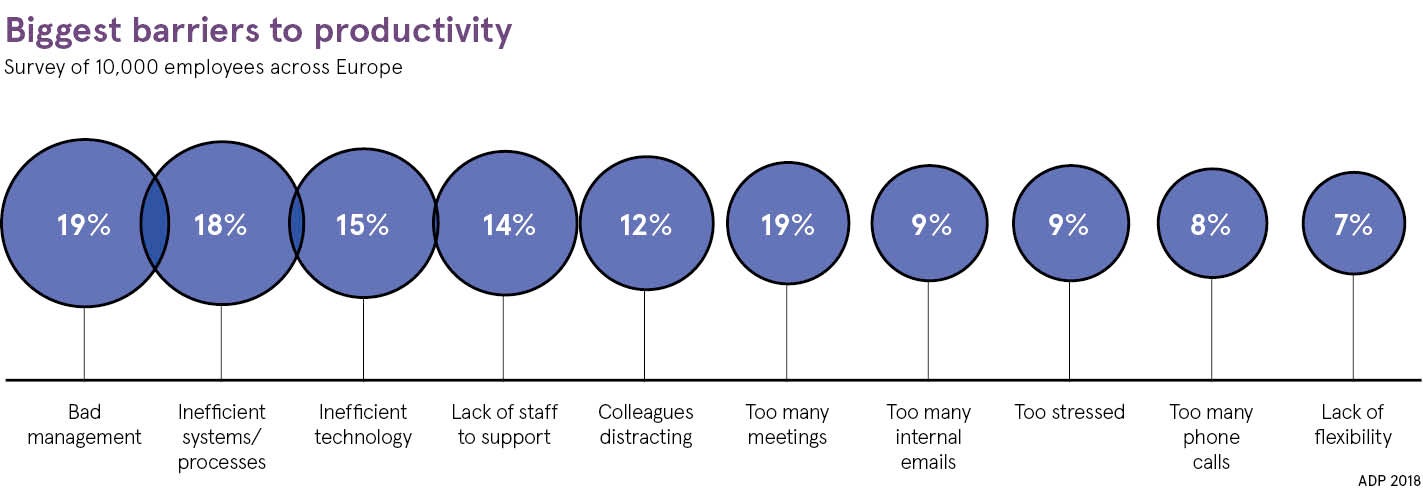

The biggest barriers to productivity

A rare but valuable insight into how employees, rather than bosses, view productivity is provided by the payroll and human resources services outsourcer ADP, which provides an annual barometer of coal-face attitudes to a wide range of pressing employment issues.

The firm’s Workforce View in Europe 2018 report, involving a sample of some 10,000 staff based in key European markets, found that a fifth of respondents say they only reach maximum productivity at work “some of the time”.

One in ten staff are “rarely or never” able to be at their most productive, with the UK, followed by Germany, appearing to have the biggest problems in this area.

Across all markets, the three biggest barriers to greater productivity, says the study, are bad management, named by 19 per cent of respondents, inefficient systems and processes (18 per cent), and slow, inefficient technology (15 per cent). Too many meetings and internal emails were viewed as more minor issues.

Whether it’s over-management twinned with command and control or simply the proliferation of chiefs at a time when Indians may be thin on the ground, poor or incompetent leadership then has a direct link to static productivity.

No one-size-fits-all solution for increasing productivity

For firms which may have already rooted out unsuitable managers, understanding why one employee may feel fully engaged at work and another may feel indifferent to the fate of the business requires a nuanced approach, says Jeff Phipps, ADP’s managing director for the UK and Ireland.

“Good managers will innately understand their people and be aware that while person A needs additional responsibility to become more productive, person B may require a lessening of the load,” he says.

“What is unhelpful is the belief by some managers that zero-growth productivity can be managed by a single, blanket tactic, even though each of us has individual desires and motivations.”

With the ADP study finding that some 47 per cent of European staff are driven by pay and remuneration, can fatter wage packets alone solve the productivity puzzle?

No, says Ben Willmott, head of public policy at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. “A fair reward for what you do is important to executive and factory floor alike, but throwing money at the problem of low productivity won’t be sustainable if there are other underlying issues,” he says.

“By giving people a pay rise, but also allowing them to be put under extreme amounts of stress, for example, any uplift in output will prove temporary.”

Good managers must make sure their staff are engaged

Mr Willmott argues that having the right skills for the job, together with being offered ongoing professional development, can play an important role in boosting individual performance, as can flexibility when it comes to a tussle between work and caring responsibilities.

If a line manager fails to motivate their staff, or actively demotivates them via favouritism or bullying, the impact on productivity can be profound, he warns.

“All the evidence shows that by pursuing progressive people management policies that allow staff to thrive, engagement and productivity tend to rise.”

For Mr Phipps, a good manager takes pains to smooth the path for the team. “While managers shouldn’t expect the term productivity ever to become a warm and fluffy concept, there are obvious things they can do to help people feel more engaged without ever using the ‘p’ word,” he says.

“Every job has its frustrations and obstacles, and it’s up to a good manager to see what they are and help overcome them, rather than pretend they aren’t there or attempt to blame the workforce for them.”

Naturally able managers, he believes, are determined to make the most of the team they already have, rather than assume they can do better by hiring replacements. They also take time to demonstrate their recognition that every member of staff makes a valuable contribution.

Ultimate responsibility for productivity lies with leaders

Whether it’s excessive corporate pay in the face of wage freezes or oppressive micro-management, Mr Danker agrees that when it comes to poor productivity, the ultimate responsibility must rest with an organisation’s leadership.

“Having visited and talked with hundreds of businesses about the steps to greater productivity, I can report that highly engaged leaders lead directly to more productive staff, but only if they recognise it’s the workers, not the managers, who have the solutions to their problems,” he concludes.

“By giving staff the space and time to explain which aspects of the organisation’s processes and procedures most need to change, and by then acting on their suggestions without delay, you are highly likely to see a rise in both engagement and productivity.”

Reason for low productivity is a lack of engagement with our work

The biggest barriers to productivity

No one-size-fits-all solution for increasing productivity