Sales targets are an essential component of any business strategy. When leaders set unrealistic goals, however, they open their business to massive risk.

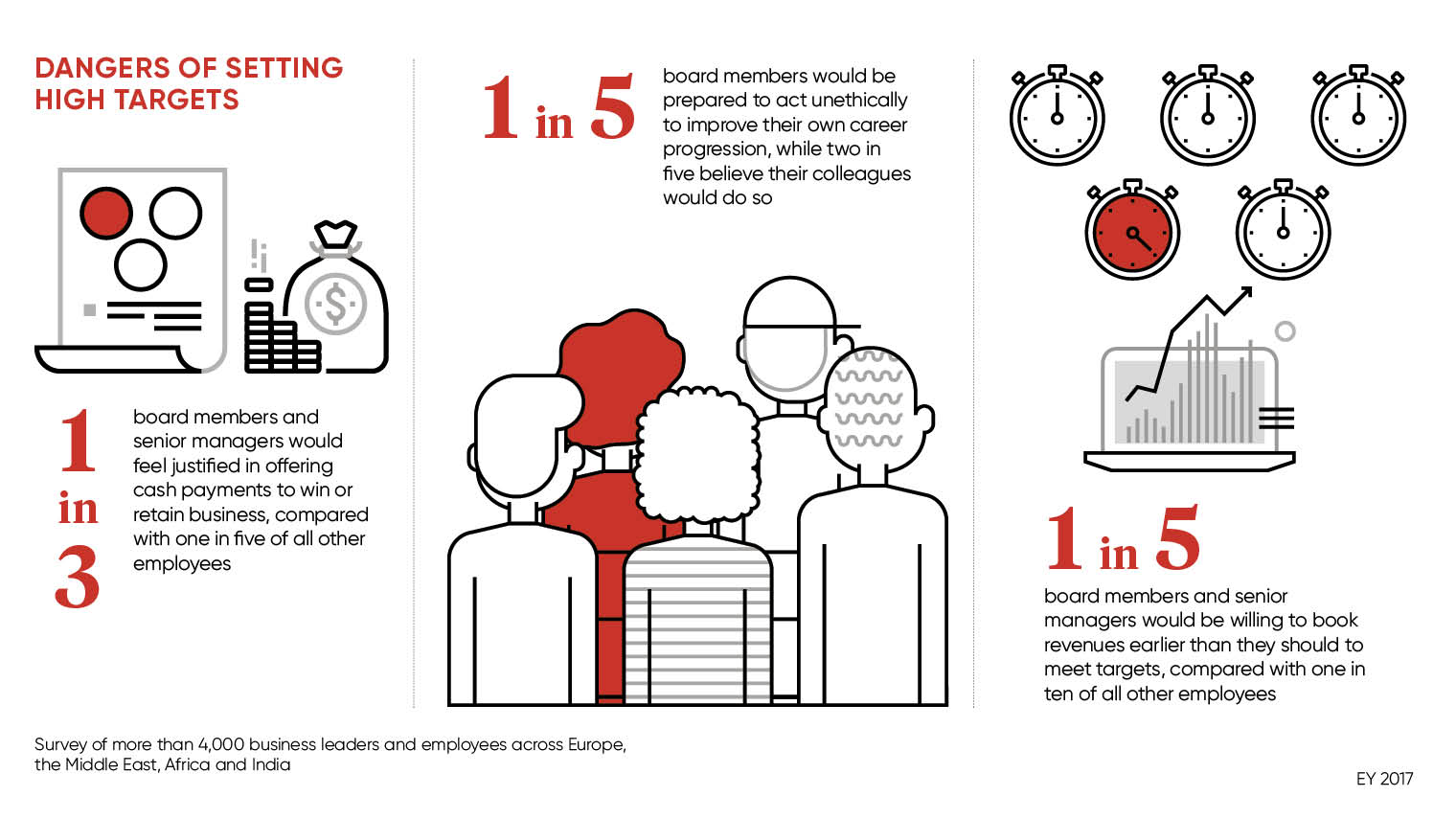

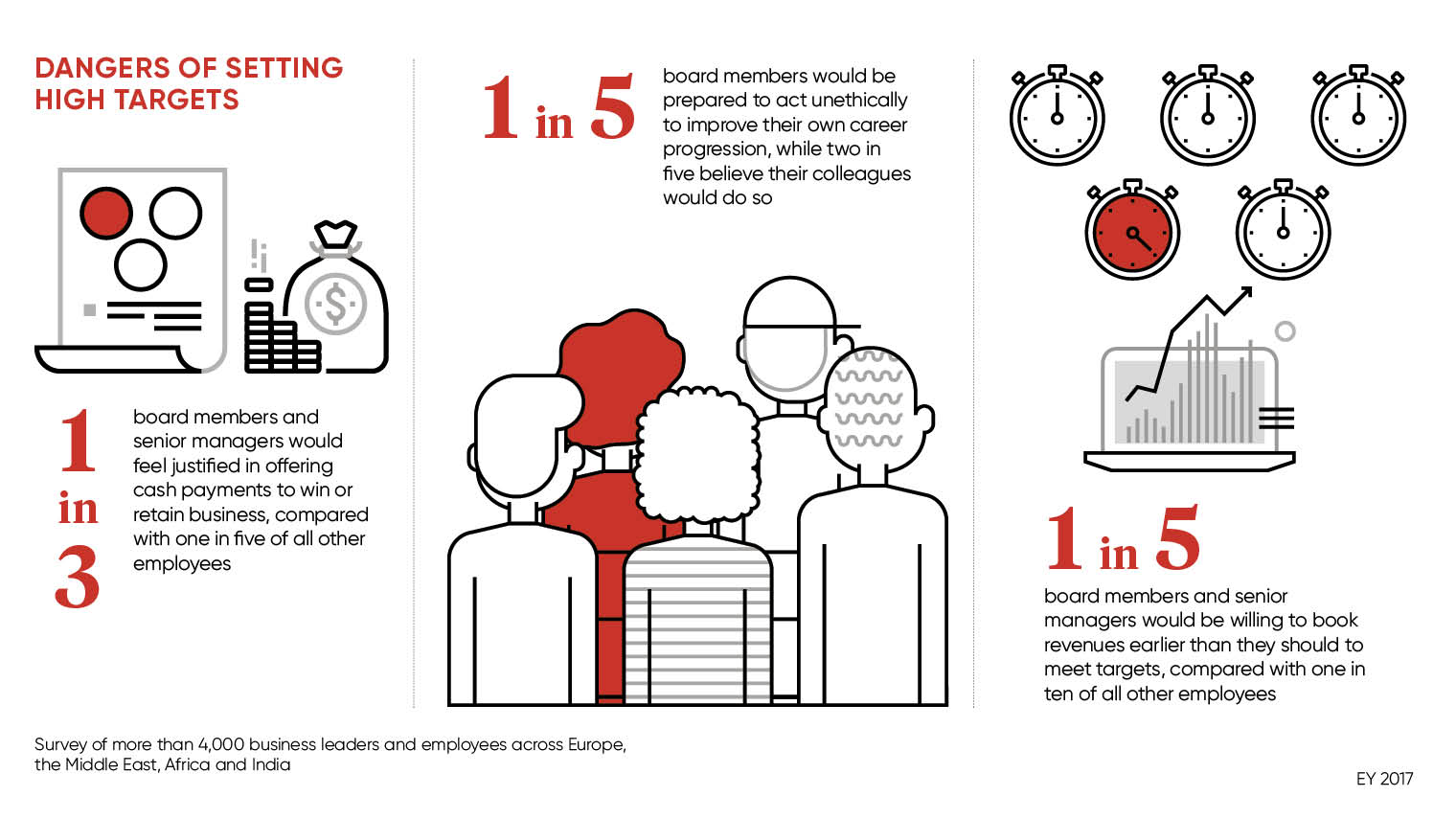

The dangers of overly aggressive sales leadership and the resulting hungriness of staff to satisfy management are highly evident. A fifth of employees and a third of senior executives now claim they can justify offering cash payments in return for business, according to the latest Europe, Middle East, India and Africa fraud report from professional services firm EY. A fifth of managers would be willing to book revenues early to meet targets.

In a tough global environment, staff may be tempted more than ever to break rules. “Businesses are operating in an increasingly uncertain world driven by a period of rapid political, regulatory and economic change. This environment has created new risks for companies as they seek to meet ambitious revenue targets,” EY notes in its report. Globally, nearly a quarter of people justified offering entertainment to help win important business.

These problems exist in all industries, but are notably entrenched in finance. Even after the 2008 financial crash and the deluge of regulation that followed unethical selling remains rife. Among the most serious examples is US bank Wells Fargo, which tasked regular cashiers with cross-selling large numbers of products to customers. Employees created more than two million fake bank accounts as they strove to meet their targets, before the problem was finally brought to a grinding halt last September.

Professor Paul Fadil at the University of North Florida, who co-authored a paper with a damning verdict of financial industry practice, says unethical selling remains prevalent. “Companies need to be able to separate sales and service,” he says. “If you buy a car, you go to the showroom and you expect to be sold to, and for servicing you go to a different desk at the back. This is still not necessarily the case in banking.”

Other industries have faced their own sales scandals. Car manufacturer Volkswagen was famously caught for fooling emissions tests to get its vehicles into showrooms. In the pharmaceutical industry, GlaxoSmithKline offered expensive entertainment to doctors willing to prescribe its pills.

Organisations that tie a larger percentage of salespeople’s earnings directly to achievement of targets need to be especially attentive to the risks of mis-selling, according to Jason Angelos, a senior managing director at Accenture Strategy. Banking, insurance, high tech, retail and car businesses, he says, “tend to have more target-based incentive programmes with a larger percentage of variable pay”.

They also need to watch out that their sales goals remain fair and they are sensibly measured. “It is unrealistic sales targets and reward systems, which only consider whether the target was achieved with little or no weight on the ‘how’, that can encourage unethical behaviour,” says Maryam Hussain, a partner in fraud investigation and dispute services at EY.

When targets become dangerous

Goals can drift towards the unachievable when there is a shift in business landscapes, according to Marc Hodak, a partner at governance firm Farient Advisors. Problems include “lack of familiarity with the market one is dealing with or disruptions in the middle of a performance period, making what may have been realistic goals suddenly unrealistic”, he says. This can be at its worst during downturns.

Targets can also become dangerous when they are excessively narrowed. In her co-authored paper, Goals Gone Wild, Professor Lisa Ordóñez of the University of Arizona warns this targeting can lead to “a narrow focus that neglects non-goal areas, distorted risk preferences, a rise in unethical behaviour, inhibited learning, corrosion of organisational culture and reduced intrinsic motivation”.

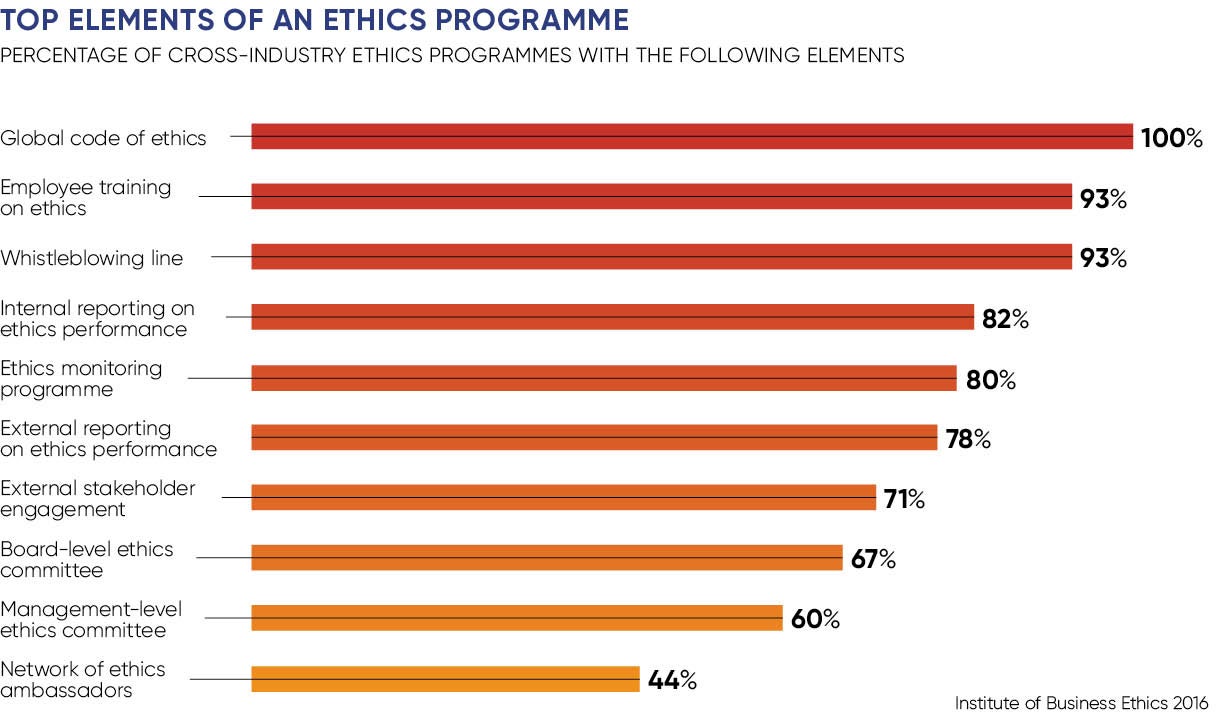

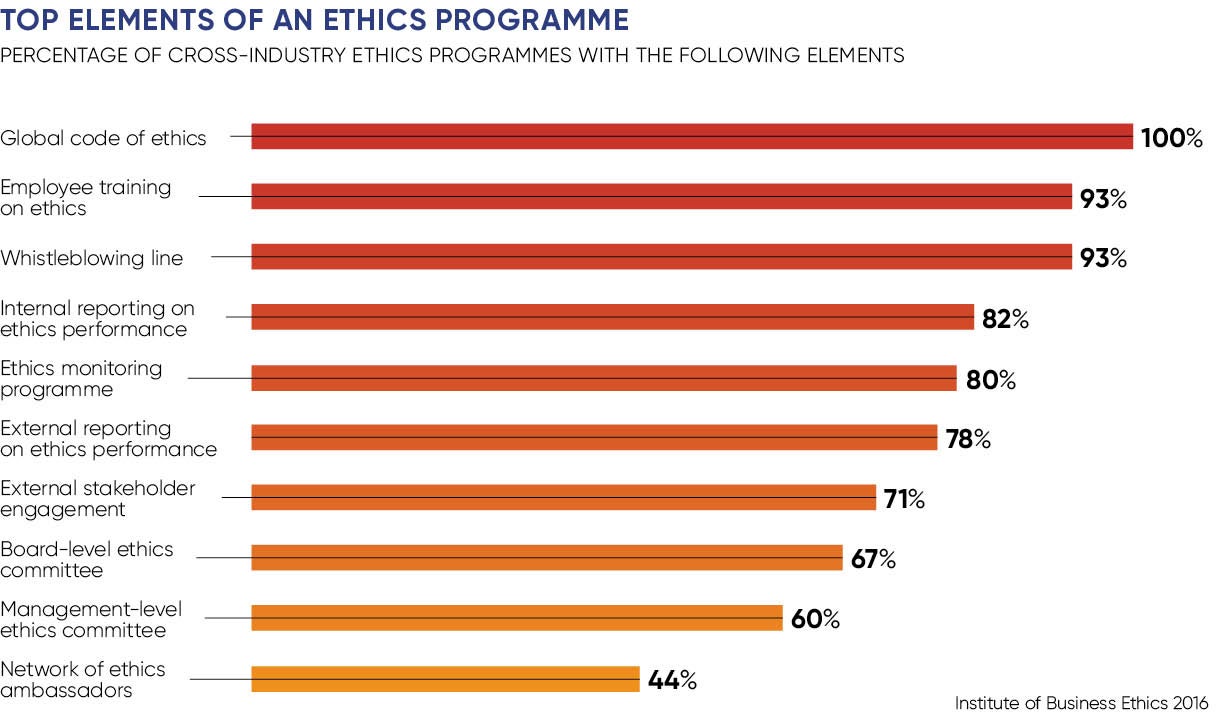

Given the complex consequences of these problems, regulators have picked on several large breaches of trust to scare other rule-breakers. Sensing the danger, many companies are establishing stringent processes for staff and they are using technology to help check adherence. The resulting data helps stamp out pockets of problems early on.

“Although the vast majority of people behave in an ethical and honest way in all business dealings, there will always be some who seek to bend or circumvent rules, and when the pressure is on, sometimes that can be a problem,” says Piers Wilson, head of product management at technology firm Huntsman Security. “Monitoring for compliance breaches, unauthorised data accesses, transfers or modifications, or other ethical issues, is a perennial challenge that business must meet.” Organisations can achieve success by policing access to customer data and controlling changes to account details or products.

Naturally, any monitoring relies on having the right basis against which it can be measured and this can only be established by leaders. “Control first and foremost needs to come from the companies themselves, from the chief executive down through the chief sales officer and the layers of management beneath,” says Mr Angelos. “Vigorously communicating the guiding principles and core values of the company, and being clear on expectations, helps to enforce the governance framework.”

To avoid unethical behaviour, firms “need to be grounded in a culture of ‘always doing the right thing’ for the customer, they must commit to never compromising on compliance, and ensure balanced company and individual goals”, he adds. “Companies can quickly get into hot water when they start bending their compliance rules on seemingly small items, which can rapidly give way to complacency in the sales organisation.”

Leaders must also choose to work only with those who will respect rules, Mr Hodak explains: “The best you can do is to hire people of integrity, deal with people of integrity as much as possible and be ready to walk away from either dishonest employees or dishonest customers, even if they are temporarily profitable.”

The right risk can then be healthy. Companies with the most effective risk cultures “might, in fact, take a lot of risk, acquiring new businesses, entering new markets and investing in organic growth”, according to McKinsey partners Alexis Krivkovich and Cindy Levy in their article Managing the people side of risk. Strong cultures, they note, openly acknowledge and discuss risk, enable transparency at all levels, and set and communicate rules that are practical for day-to-day work.

Such a carefully judged risk environment must be maintained during both times of success and of decline. “The biggest pitfall to avoid is the idea that if everything is going great, there is nothing wrong,” says Mr Hodak. “This is especially true when the good times falter and business begins to turn down; that is when the pressure to keep growing is at its most challenging and when people, who are merely creating the illusion of growth, are most likely to be overlooked.”

Worryingly, businesses regularly make a dire mistake in this regard, failing to examine those who are visibly excelling. “Companies should consider introducing increased monitoring of high performers to ensure that the performance was ethically achieved,” says Ms Hussain. “Introduction and communication of such measures, and consequences for those who engage in unethical activities, will make ethical considerations a core issue, as opposed to a peripheral issue, for employees focused on achieving their sales targets.”

If they are to eliminate unethical selling, companies must respect their environment and their individuals. Managers have to consider what they are encouraging and in appraisals, Professor Ordóñez says, they must look at the methods staff use to achieve results. “If they met the goals using shortcuts, unethical practices and high-pressure tactics, then they should not be rewarded,” she concludes.

It is only through such stringent and careful management that a company’s sales will not turn bad.

When targets become dangerous