For decades a remote working revolution has been predicted, but until the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic it had not arrived. While the revolution has yet to benefit the majority of blue-collar workers, white-collar staff across the world, previously based in offices, are reaping the rewards of working from home, including a better work-life balance, reduced physical health risks and lower living costs.

The rise in remote working, jet propelled by the pandemic, has been heavily skewed towards highly paid, white-collar jobs and a huge proportion of the global workforce doesn’t have the same luxury. As a result, there are concerns over a growing new social divide, which is worsening long-established inequalities.

Research published in June by the University of Chicago found 37 per cent of jobs in the United States can be performed entirely at home or, in other terms, nearly two-thirds cannot. Based on an assessment of more than 800 occupations to classify the feasibility of working from home, the researchers then used US Department of Labor surveys to see how many of each of these jobs exist in America.

“The pandemic has widened inequality,” says Dr Jonathan Dingel, co-author of the study and the university’s associate professor of economics. “Those who cannot work from home face a nasty trade-off between protecting themselves from the disease and protecting their paycheck.”

According to Dingel’s research, the industries best suited to going remote are well-paid, white-collar occupations in large cities, whereas blue-collar workers in sectors such as agriculture and hospitality are finding it much more difficult or even impossible to pivot, which means some could be severely impacted while others are relatively unscathed.

“The collapse of the restaurant and entertainment industries has been hard on the lower-wage workers in those industries,” he says. “And there is also a broader set of concerns related to the fact that many service economy jobs, which cannot be done from home, are supported by the white-collar office jobs that, in principle, could be done remotely.”

Widening poverty and inequality for blue collar jobs

Dr Juan Palomino, an economist at the University of Oxford who worked with colleagues from the Complutense University of Madrid to analyse the impact of the pandemic in 29 European countries, similarly found that remote working in Europe is strongly tied to higher earnings. The team concluded that social distancing and lockdown measures could create a sizable increase in poverty and inequality, suggesting existing income inequality could be compounded by the gap in access to the benefits of remote work.

Their findings, published in October in the European Economic Review, found women are less affected in their jobs than men on average, but that temporary, part-time and self-employed workers are, in general, worse off. “If you are essential and frontline workers, you are exposed to risks of course, namely health risks,” says Palomino. “But the most vulnerable in our simulation are workers in closed, non-essential sectors.”

He nonetheless distinguishes between blue-collar workers in factories and those working in the services industries who require in-person contact with customers. “The blue-collar industry was affected in initial lockdown, but it’s not so much affected now,” he says. “Factories have reopened, for example. The sectors more likely to be closed are the ones with face-to-face contact. The divide isn’t exactly blue collar white collar.”

But Dr Martina Bisello, research officer for the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, argues the pandemic has opened up more opportunity for some lower-paid white-collar workers, with the share of employees in the European Union’s 27 member states working from home now at 48 per cent. “The typical profile of a remote worker was high skilled, high paid, typically white collar,” she says. “The COVID crisis has, in some ways, neutralised and equalised the access for remote working for people, allowing younger workers the opportunity too.”

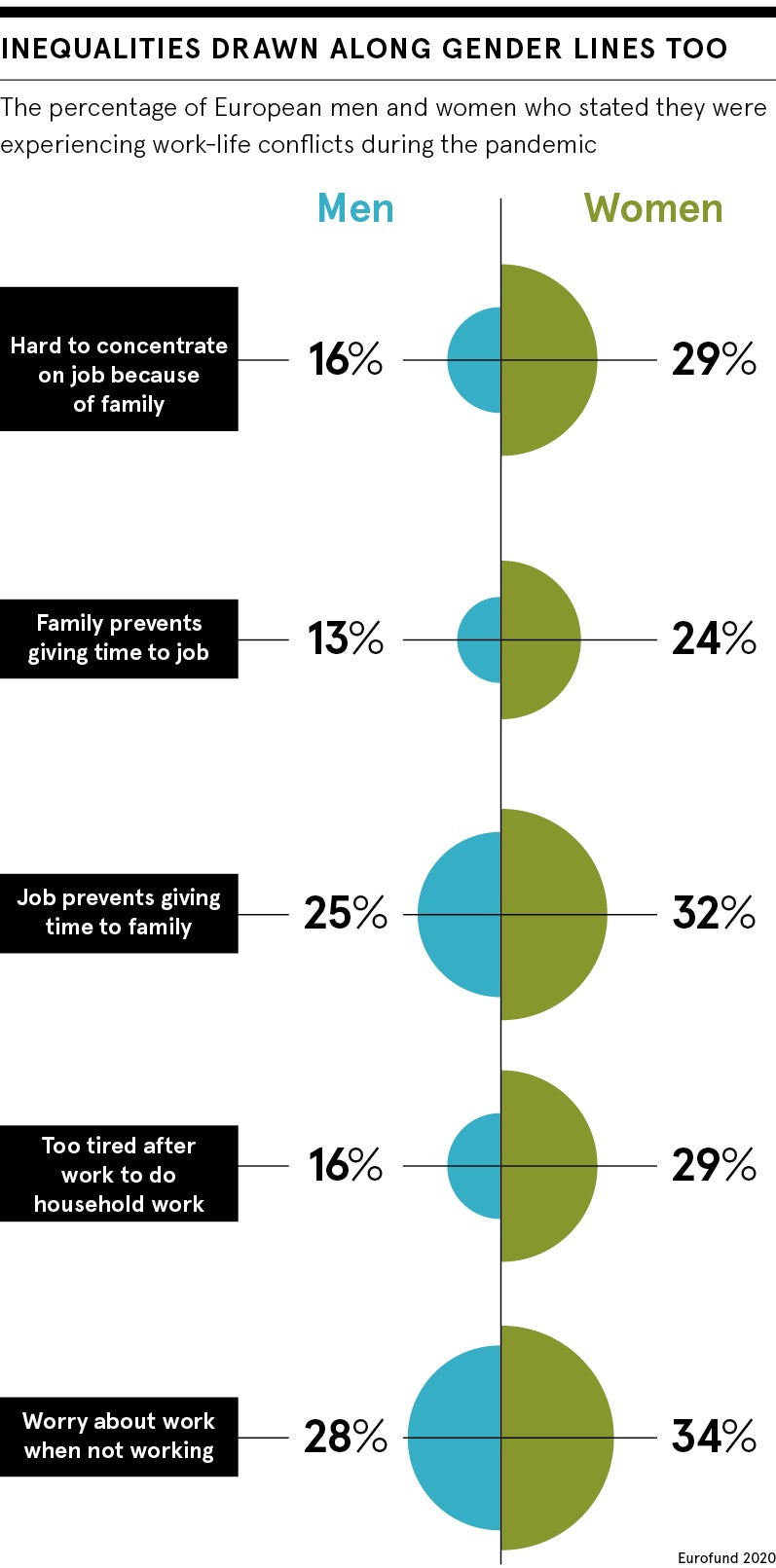

Bisello, who studied the effect of the pandemic on more than 130 occupations, also found dramatic differences in the “teleworkability” of jobs, by wages and by education level. Further inequalities, she says, could emerge from an increase in the household burden on women, juggling work, home-schooling and care.

Race a factor for remote employees

However, race-equality experts are concerned that Black and ethic-minority blue-collar workers could be left in even more precarious and disadvantaged situations due to the shift to remote working, not only in the short term, but for years to come.

“We know from our research that Black and minority-ethnic people are featuring disproportionately in essential work, as high-risk key workers,” says Nick Treloar, research analyst at the Runnymede Trust, a leading independent race-equality UK think tank. “It’s disproportionately and detrimentally affecting them. Basically all the risk factors are higher for them.”

Treloar says the inequalities are not only a race issue, but one involving class and poverty. “If you take Uber drivers, you have an overwhelming number of ethnic minorities,” he says. “You’re asking them to choose between putting food on the table and avoid getting the virus, which is a very hard choice to give them.”

Factors such as lower levels of savings and the fact that Black and minority ethnic people tend to live with more people in smaller households mean the impact of the pandemic has been particularly severe on them, he adds.

What can be done to close the gap?

Treloar argues that governments could do a number of things to help counter this inequality, including providing temporary housing for those who test positive, offering state-backed financial support for those who need to self-isolate and therefore cannot work, as well as helping to provide IT equipment for those who cannot afford it.

“They could solve it quite easily,” he says. “It would be better if the government supported the most vulnerable with the tools they need. It’s time for action because race is still a social determinant of health in 2020 and we know the solutions.”

Dingel at Chicago University believes a period of substantial experimentation is necessary on the part of companies and governments to help reduce inequalities for blue-collar workers. “Companies, workers and governments are now exploring a much wider variety of working arrangements than before the pandemic,” he says. “There’s a lot of uncertainty because there’s a lot to learn.”

The government has to realise not everyone has lost in economic terms to the same extent

Governments must attempt to envisage what aspects of remote working will remain in the long term and what the implications of this are, adds Oxford’s Palomino. “Before it was a white-collar blue-collar divide, but now there will be those whose in-person work is restricted versus those whose work is unrestricted and those who do remote working,” he says. “The government should ensure remote working is possible for as many people as possible, but we will always need people doing retail.”

Palomino says a form of furlough scheme may need to be made permanent to provide better job security for certain industries and this could be paid for in taxes by industries that have not suffered. “The government has to realise not everyone has lost in economic terms to the same extent,” he says. “Policies and tax schemes should adapt to this and those who have done well economically may have to pay higher taxes to share the burden.”

For decades a remote working revolution has been predicted, but until the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic it had not arrived. While the revolution has yet to benefit the majority of blue-collar workers, white-collar staff across the world, previously based in offices, are reaping the rewards of working from home, including a better work-life balance, reduced physical health risks and lower living costs.

The rise in remote working, jet propelled by the pandemic, has been heavily skewed towards highly paid, white-collar jobs and a huge proportion of the global workforce doesn't have the same luxury. As a result, there are concerns over a growing new social divide, which is worsening long-established inequalities.

Research published in June by the University of Chicago found 37 per cent of jobs in the United States can be performed entirely at home or, in other terms, nearly two-thirds cannot. Based on an assessment of more than 800 occupations to classify the feasibility of working from home, the researchers then used US Department of Labor surveys to see how many of each of these jobs exist in America.