It is possible we could have another election ahead. The hung parliament may fail, triggering a second general election. And if that day comes, all political parties will be furiously trying to get an edge.

One tip would be to hire a project manager to run the campaign. Traditionally the top brass are drawn from a motley crew of advertising men, ex-politicians and consultants. Often being good mates with the party leader is qualification enough.

As one Labour politician said of the Remain campaign in the EU Referendum: “The four principal staff of the Stronger In campaign all grew up within two square miles. Two went to the same north London state school. One’s father was Labour home secretary, another’s godfather was Peter Mandelson.” The campaign was crying out for an expert.

What project managers can offer

There are three virtues offered by a project manager. The first is clarity. Project managers are taught to identify their objectives as early as possible. These must be quantifiable and defined with precision. A factor in Ed Miliband’s 2015 election loss was his use of clever, but unclear, terminology such as “predistribution” and “producers not predators”. When asked to clarify he struggled. Project managers are drilled in the art of asking for elucidation. Waffle, bluster and fudge don’t fit in a Gantt chart.

A second asset of project managers is their reliance on numbers. If you are managing a multi-billion-pound scheme, such as Crossrail or High Speed 2, then mastery of the digits is essential. The entire operation revolves around numbers, financial and calendar. This can be a revelation in politics where hunches and instinct rule.

The strength of project managers is the ability to co-ordinate multiple groups of people

The importance of numbers in political campaigning was brilliantly demonstrated in the Referendum campaign. The head of Vote Leave, Dominic Cummings, wrote about how he converted campaigning into a numbers game: “One of our central ideas was that the campaign had to do things in the field of data that have never been done before.” He took data from every source, including social media, online advertising, websites, apps, canvassing, direct mail, polls, funding and activist feedback, and then hired physicists to do the maths. This determined which slogans to use – the Go Global message “was a total loser” – which streets to canvass on and which online ads were delivering the most clicks.

The contrast between his project management-style approach and the emotional guesswork of the old school campaigners is astonishing. Mr Cummings said: “Many big-shot traditional advertising characters told us we were making a huge error. They were wrong. It is one of the reasons we won… If you want to make big improvements in communication, my advice is hire physicists, not communications people from normal companies and never believe what advertising companies tell you about ‘data’ unless you can independently verify it. Physics, mathematics and computer science are domains in which there are real experts.”

The third strength of project managers is the ability to co-ordinate multiple groups of people. And boy is this important in campaigning. There are 650 constituencies to contest in the UK, each with a candidate, party chairman and agent who manages the local effort. There are the party members; as of March, Labour had 517,000, the Conservatives 149,000, Liberal Democrats 82,000 and the Greens 55,500. Amateurs can’t work on this scale.

It’s the campaign manager’s job to mobilise this army. For politicians, this may be new territory. For project managers, it’s a core skill. The Association for Project Management includes people management as a fundamental part of the curriculum. This will help with the ground war.

With a project manager in charge, the campaign will run like clockwork

Former LibDem campaign managers Mark Pack and Edward Maxfield, in their book 101 Ways To Win An Election, advise recruiting one volunteer for every 200 voters. This makes jobs like leafleting less arduous, and gives the campaign energy and momentum. The trick is to give people the right tasks. “Taking time to match the skills of your team to the tasks at hand can pay major dividends in the effectiveness of your campaign,” they advise. Sometimes it’s necessary just to let people do what they want. They are volunteers after all.

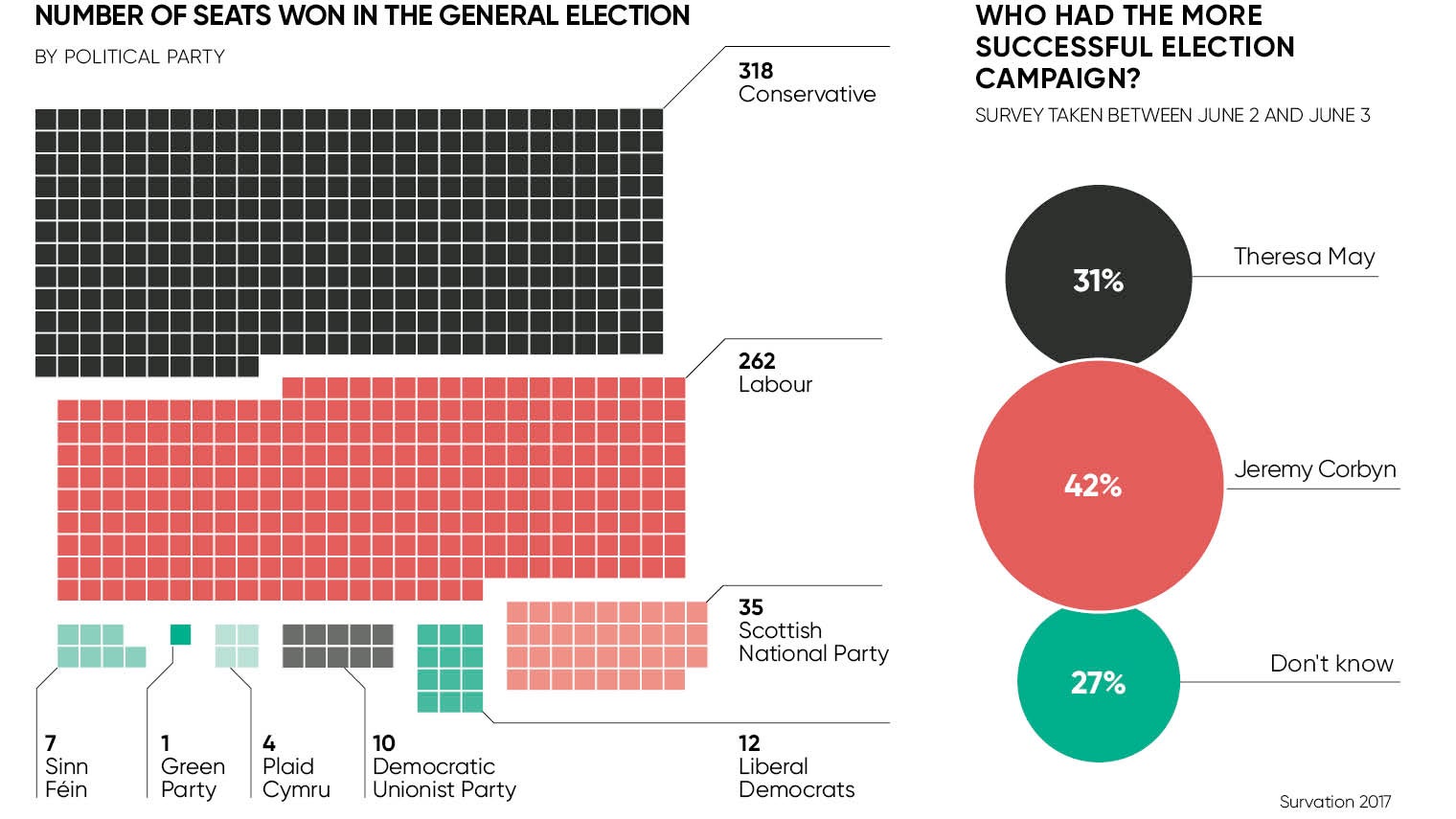

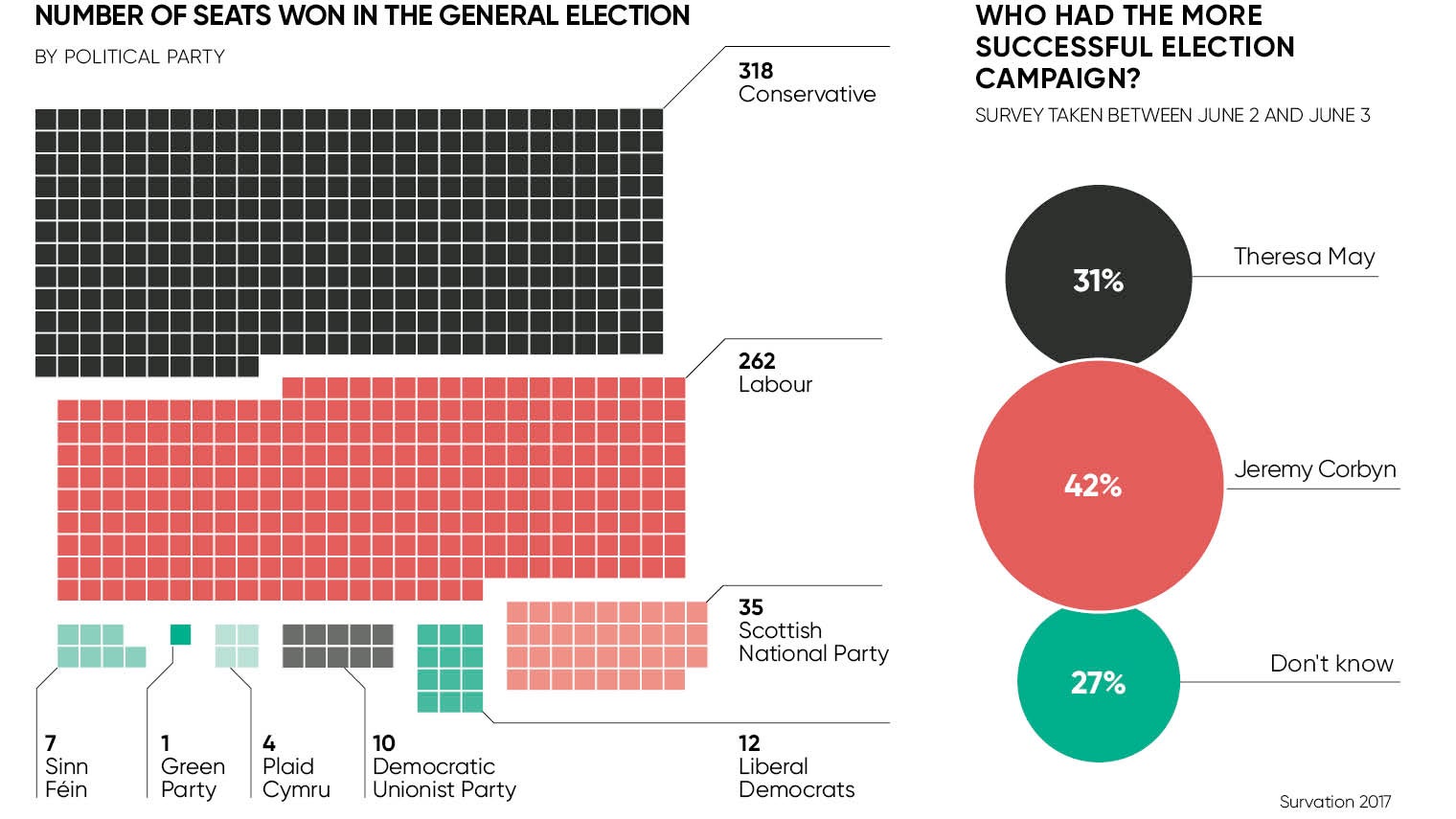

As the campaign is running, a project manager will find duties easier to handle than consultants. Project managers are master delegators. They don’t try and do everything themselves. The disastrous Conservative 2017 campaign stemmed from a lack of delegation. Theresa May’s chief advisers worked a narrow cabal, dominating the manifesto and dictating tactics.

Katie Perrior, the well-regarded director of communications who resigned before the election, called the office “pretty dysfunctional” and “toxic”. She pointed to a power struggle that sprawled out of control. “For all the love of a hierarchy, the chiefs treated cabinet members exactly the same – rude, abusive, childish behaviour,” she said. A project manager never makes this error. They harness the talents of their troops. There’s no point usurping other roles.

With a project manager in charge, the campaign will run like clockwork. The elements are too numerous for untrained punters to handle. There’s the online campaign, finance, telephone banks, leaflet printing and delivering, booking interviews with the media, hiring photographers, and making sure everyone’s fuelled up on a limitless supply of tea and biscuits.

None of the campaigns in the recent election was regarded as optimal. A change of professionals at the top is long overdue.