Over the past year, economists have grown increasingly alarmed about the rise of so-called zombie companies. Although not yet insolvent, these businesses are left to shamble along aimlessly, not earning enough to reinvest in the business but still turning over a sufficient amount to pay off debts. Now, as COVID restrictions lift and economies reopen, these undead firms could prove to be a curse for hopes of a strong economic recovery.

Unlike their horror movie counterparts, these businesses can be identified by a lack of profitable activity and high levels of indebtedness, with the majority of their cashflow going towards servicing these debts. Sandy Hager, senior lecturer in international political economy at City University London, describes US department store JCPenney and collapsed British construction company Carillion as two classic examples.

Julie Palmer, partner at corporate restructuring specialists Begbies Traynor, explains: “A zombie business is one which is hanging on for grim life but isn’t really prospering and can do little more than just survive.”

Government support schemes, low interest rates and access to cheap credit has helped to keep many of these companies in a state of suspended animation. It has also caused the number of these zombie businesses to soar.

Towards the end of last year, analysis from Bloomberg revealed that almost a quarter of companies listed on the Russell 3000 index — the 3,000 largest publicly traded companies in the US — had not earned enough to pay off the interest owed on their debts and could therefore be classified as zombies.

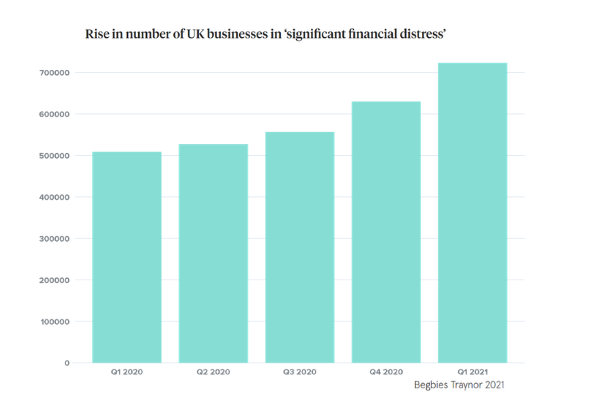

In the UK, new research from Begbies Traynor shows similarly distressing signs for the UK. Its Red Flag Alert report found 723,000 businesses in ‘significant financial distress’, a 15 percent increase from the previous quarter and a 42 percent increase year on year.

Palmer adds: “The combination of the long-term build up of these zombies and the turning off of support measures, which is going to have to happen, will finally mean that we start seeing a number of these businesses begin to fail, and in quite significant numbers.”

What does the zombie company outbreak mean for the economy?

While the justification for supporting businesses through the pandemic has been clear, as economies reopen people are beginning to question whether these unproductive businesses should be left to exit the market.

Research from the Bank of International Settlements suggests that a prevalence of zombie firms could hamper post-pandemic economic recovery. Speaking on the BIS podcast, its senior economist Ryan Banerjee says: “We’ve seen fewer bankruptcies, which means there have been fewer new entrants in the market, as there has been no space for them to occupy. That means there is potentially less chance for one or two of those new fast-growing firms, which have an outsized impact on productivity growth, to enter the market.”

This could lead to a much slower pace of economic recovery and caused Deutsche Bank chief executive Christian Sewing to warn of the “serious impact” zombie companies could have on the productivity of the economy.

For Palmer, the harsh reality is that many of these zombie firms need to fail in order to encourage a faster economic recovery.

“If better businesses are able to come into the spaces they [zombie businesses] occupied and do things more imaginatively and flexibly, they will not only survive but adapt and prosper going forward,” she says. “Although it means a bit of pain in the short term, it’s the price to be paid for a more efficient economy and a sharper recovery curve going forward.”

We shouldn’t be overly excited about the prospect of COVID killing off these so-called zombie companies

But not everyone is welcoming the downfall of these zombie corporations. Hager, says: “You’ll find a lot of pro-market people who are celebrating the fact that so-called zombie companies might go bankrupt during the crisis. They’re seen as being incapable of competing and if they fail, we might be able to create a more efficient business sector.”

However, he cautions: “We shouldn’t be overly excited about the prospect of COVID killing off these zombie companies because they’re the ones that are a key source of dynamism in the economy.”

According to his research, smaller businesses, which are more likely to be classified as zombie companies because of their high debt servicing costs, are also the ones that spend the largest percentage of their revenue on capital expenditure.

Hager adds: “Capital expenditures matter because they provide the basis for innovation and job creation. Without these smaller companies, we’re going to see a greater concentration of power within the larger corporations, more monopolies and less capital expenditure.”

Ultimately, Hager fears this could lead to slower job creation, wage stagnation and unemployment, as well as lower levels of innovation in product markets.

But not all zombie companies are doomed to fail. Pent up consumer demand, which has built up during lockdowns, could help some of these businesses shed their zombie status. Hager says: “It’s difficult because these businesses are dedicating so much of their cashflow to debt servicing, making it hard to compete. But I wouldn’t say that their demise is inevitable.

“The rapid reopening up of the economy and increase in consumer demand could be enough to help a lot of these companies to bounce back, especially in the hospitality and travel sectors.”

Over the past year, economists have grown increasingly alarmed about the rise of so-called zombie companies. Although not yet insolvent, these businesses are left to shamble along aimlessly, not earning enough to reinvest in the business but still turning over a sufficient amount to pay off debts. Now, as COVID restrictions lift and economies reopen, these undead firms could prove to be a curse for hopes of a strong economic recovery.

Unlike their horror movie counterparts, these businesses can be identified by a lack of profitable activity and high levels of indebtedness, with the majority of their cashflow going towards servicing these debts. Sandy Hager, senior lecturer in international political economy at City University London, describes US department store JCPenney and collapsed British construction company Carillion as two classic examples.

Julie Palmer, partner at corporate restructuring specialists Begbies Traynor, explains: “A zombie business is one which is hanging on for grim life but isn't really prospering and can do little more than just survive.”