Tilly Lockey was a baby when she lost both hands after developing meningitis. Almost a decade later, Tilly made headlines when she received new hands created with a 3D printer, as the world’s first clinical trial of a new type of prosthesis gathered speed within the NHS in Bristol.

Tilly’s hands, based on Disney characters, took just one day to make. The lightweight design by Open Bionics, a UK firm, uses a 3D printer to create the hand in four separate parts, custom-built to fit the patient using scans of their body. Sensors attached to the skin detect muscle movements, which are used to control the hand and open and close the fingers.

The hands cost about £5,000. That compares with around £60,000 for currently available prosthetics with controllable fingers, which makes them too expensive for young children as they are growing up. 3D printing has provided a solution that simply didn’t exist until a year or two ago.

In Belfast, NHS surgeons turned to 3D printing when a lifesaving transplant threatened to go catastrophically wrong.

Pauline Fenton, 22, was living with end-stage kidney disease and was wholly reliant on dialysis. Her father William was confirmed to be a suitable living donor. However, the discovery of a potentially cancerous cyst on William’s donor kidney meant an already complex procedure would have an extra level of difficulty.

As the cyst would first require treatment before the transplant could proceed, surgeons at Belfast City Hospital made the decision to use a 3D-printed replica model of the donor kidney, printed from his CT scans.

This allowed the team of surgeons to ascertain the size and placement of the tumour and cyst, so the surgical team could plan and prepare for the surgery to remove the cyst and transplant the kidney to the patient.

Tim Brown, consultant transplant surgeon, says: “As surgeons, we are highly trained and skilled at what we do, but by having a 3D print of the patient’s anatomy in my hand, I get an extra level of understanding that just isn’t possible with 2D or 3D images on screen. In this case, I could plan the surgery in detail, considering the best approach, as well as the potential problems, before stepping into the operating theatre.”

What, precisely, is 3D printing? Also known as additive manufacturing, it is the process of creating a three-dimensional object from a digital file. It is called additive because it generally involves building up thin layers of material, one by one. The technology can produce complex shapes that are not possible with traditional casting and machining methods or subtractive techniques.

3D printing is still in its infancy, but its positive impact is already being felt

It is also cost effective, which is critical when other healthcare costs are rising inexorably. This is because the process of additive manufacturing enables items to be assembled directly from a digital model, increasing precision and removing room for error. Traditional manufacturing techniques usually rely on removal, by cutting or drilling, incurring waste and extraction costs which 3D printing avoids.

3D printing is still in its infancy, but its positive impact is already being felt, particularly in healthcare. Its development is opening up endless possibilities for healthcare systems and reframing the debate about sustainability and access to care. Just as the NHS is exploring its potential, so too are healthcare providers around the world. And the healthcare industry, from manufacturers of medical devices to big pharma, is redirecting strategic thinking to embrace 3D.

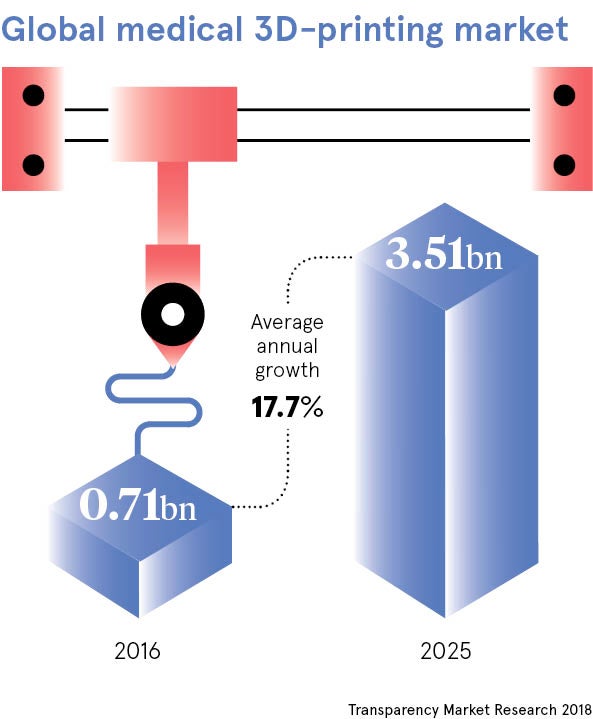

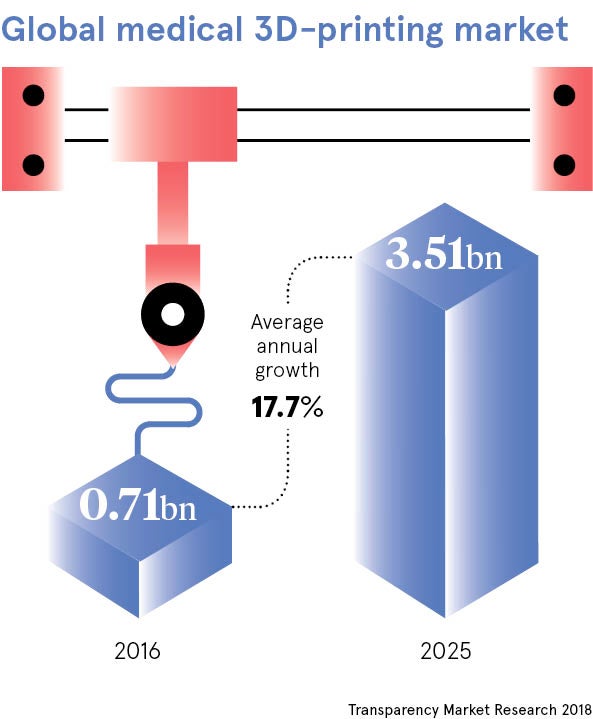

Small wonder that growth prospects for 3D printing are so strong. A report by Transparency Market Research, the business analysts, forecasts growth of around 18 per cent a year in the global 3D medical devices market to reach $3.5 billion by 2025.

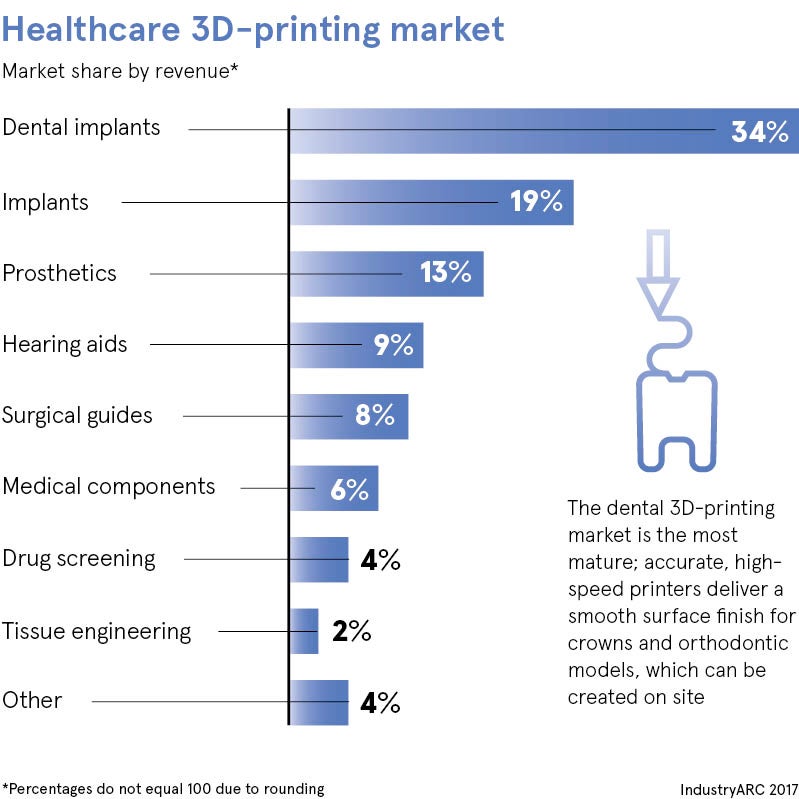

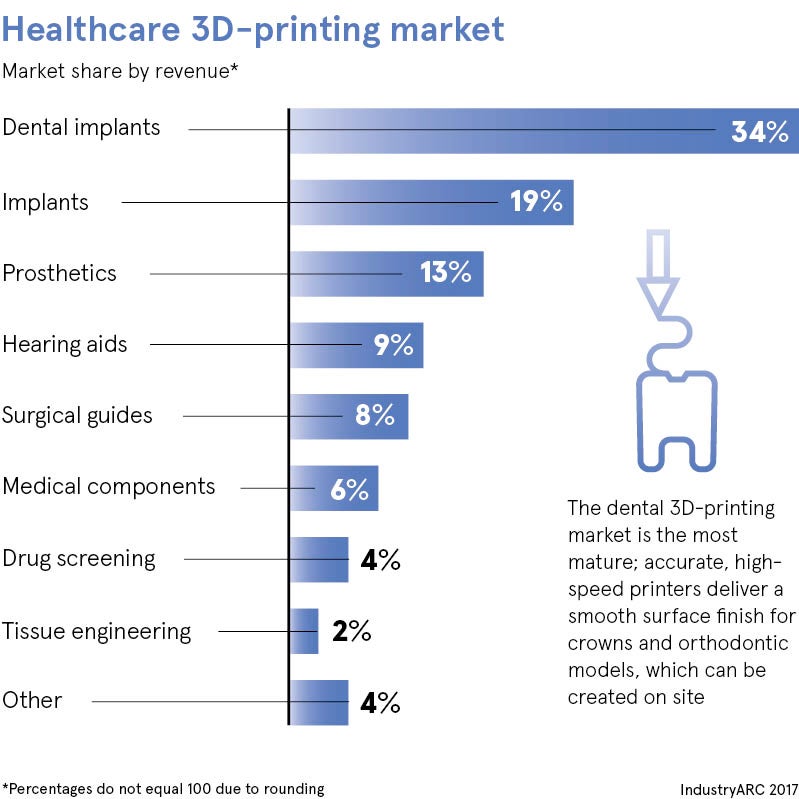

Until now, and for the foreseeable future, growth has been driven by demand for 3D-produced orthopaedic and cranial implants, and dental restoration. Digital dentistry, in particular, is bringing rapid transformation. High-speed desktop printers are extremely accurate and deliver a smooth surface finish for crowns and orthodontic models, which can be created on site, reducing the need and cost of dental laboratories.

3D printing has the potential to hasten personalised care because it enhances the ability of clinicians to provide highly customised products and treatment that is far more accurate than was possible previously.

A number of barriers must be overcome to realise the full potential of 3D printing in healthcare. As often is the case, the regulatory environment has not kept up with rapid technological advance, which means health systems are not always equipped to approve 3D-printed products. The risk of patent and copyright infringement remains a concern, and there is a shortage of technical expertise in healthcare.

The relatively high cost of 3D printers is an issue, although the emergence of an unprecedented number of small and medium-sized 3D-printing technology companies is creating an increasingly competitive business environment.

The market is also witnessing a surge in collaboration initiatives as established healthcare and medical devices companies focus on incorporating innovative technologies in their operations to attain sustainable profits and remain competitive.

Recently, Philips signed an agreement with the 3D-printing medical devices companies Stratasys and 3D Systems in North America to support its progress in the field of patient care and strengthen its clinical experience.

North Manchester General Hospital has established its own 3D-printing laboratory, within the NHS, in response to the increased demand for 3D services. The lab’s main cases are head and neck cancer patients who require reconstruction, including the use of bone grafts to reconstruct the upper or lower jaw. With new resources provided, the lab is taking on smaller cases and it may even be used in the orthopaedics, neurology or rheology departments.

Technological advances in 3D-printing materials and strategic collaboration among industry players appear set to make 3D printing the most rapidly evolving technology in medical research, with the potential to transform the healthcare landscape in the near future.

Increasingly, 3D printing will become embedded in everyday activities, from helping surgeons to improve success rates in complicated procedures to producing pills in new shapes with variable release rates. As far as healthcare is concerned, the future really is 3D.