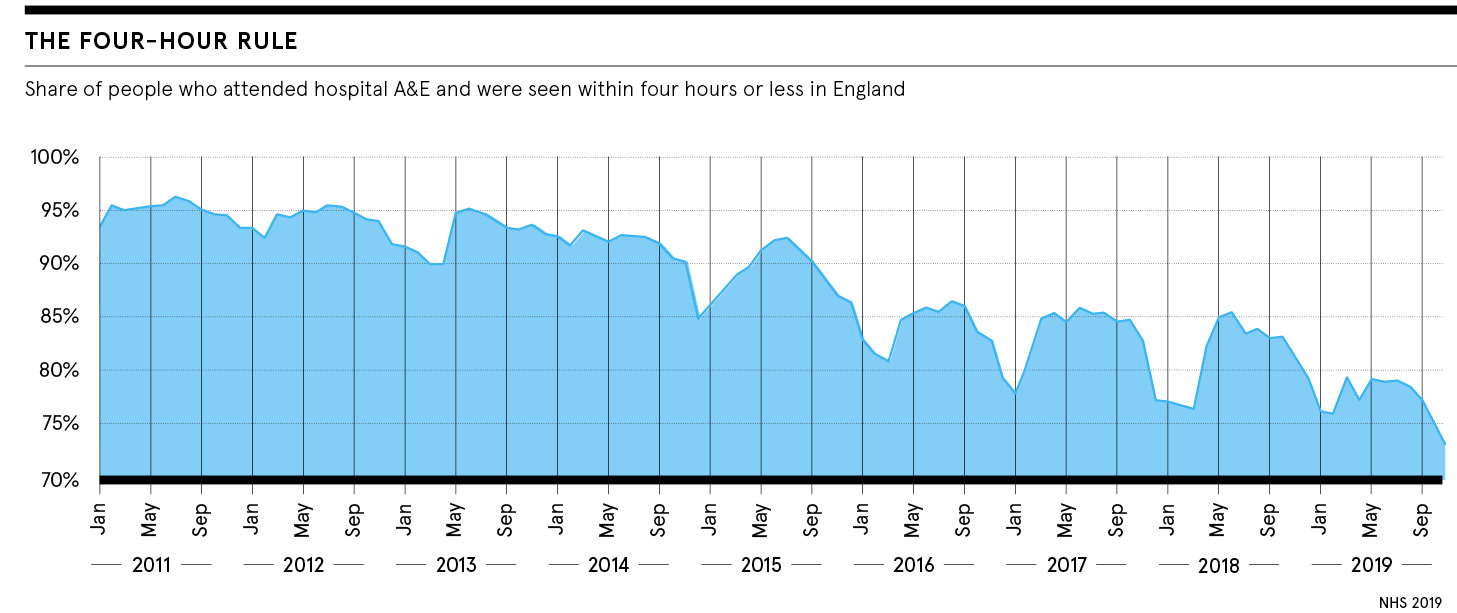

There is a political row every time A&E waiting times are published. The latest figures were no exception. They revealed that more than 100,000 patients in England waited for more than four hours to be treated in A&E in January, the highest number since records began.

Politicians, doctors and patients were all drawn into the furious debate that followed on what the numbers said about the performance of the health service.

But all this will end if the government has its way. Health secretary Matt Hancock wants to scrap the four-hour waiting target because it is no longer deemed to be “clinically appropriate”.

The move has met strong opposition. Critics say it has everything to do with the fact that the target, enshrined in the NHS mandate, has been missed for many months and is unlikely to be met any time soon, because of funding and staffing pressures.

Dr Simon Walsh, British Medical Association emergency medicine lead, says: “Targets are an important indicator when services are struggling and there is a very real concern that any change to targets will effectively mask underperformance and the effects of the decisions politicians make about resourcing the NHS.”

The government, meanwhile, says that care in hospitals has changed significantly since the target was introduced 20 years ago. Some patients who would have been admitted to hospital overnight now receive more lengthy investigation and treatment in A&E before being discharged home.

What is beyond dispute is that A&E waiting times have become a barometer for overall performance of the NHS and social care system. This is because they are affected by changing activity and pressures in other services such as the ambulance service, primary care, community-based care and social services. For example, patients cannot be admitted quickly from A&E to a hospital ward if hospitals are full due to delays in transferring patients to other NHS services or in arranging social care.

Waiting times in emergency departments

But measuring the proportion of people seen within four hours has limitations. The King’s Fund health and care think tank points out that two different A&Es could see the same proportion of patients within four hours, but have very different average waiting times.

In addition to waiting times, the quality of A&E care can also be measured through patient experience surveys and clinical indicators such as the proportion of patients who re-attend A&E within seven days of their first attendance. Other measures, such as the time a patient waits to see a clinician in A&E, are also now recorded.

A review of A&E waiting times was launched by then-prime minister Theresa May. The review is yet to be completed, but an interim report was produced by Professor Steve Powis, NHS England’s national medical director, in March 2019. He proposed three new targets: using average waiting times in emergency departments as the main measure, instead of a 95 per cent threshold; recording how long patients wait before being clinically assessed after they arrive; and checking how long the most critically ill patients wait before their treatment is completed.

Boris Johnson’s government has not committed to the recommendations and the delay has created uncertainty.

Simplicity of 4-hour target is its strength

Dr Katherine Henderson, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, says: “So far we’ve seen nothing to indicate that a viable replacement for the four-hour target exists. Rather than focus on ways around the target, we need to get back to the business of delivering on it.”

The King’s Fund’s Siva Anandaciva, policy team chief analyst, says the simplicity of the existing target for A&E waiting times is also one of its strengths. “The four-hour target is simple. Regardless of the time of day, how full the hospital is, the medical needs of the patient, every individual attending an A&E department is given a pledge that they should expect to spend no more than four hours in A&E,” he says.

Another concern for hospitals is there will be losers as well as winners. We do not yet know what the new target for average waiting times will be, but we do know the impact will not be uniform across the sector.

Something that does tend to be overlooked is the vast majority of patients are still seen within four hours of arrival at A&E. The NHS in England also compares favourably with other countries on providing rapid access to emergency care, even though performance has deteriorated in recent years.

Nonetheless, it is likely A&E will continue to be the main focus for testing the performance of the NHS for some years to come.