They call it the nerd defence. A courtroom tactic to persuade a jury of a defendant’s low propensity to commit a crime, it involves the individual in the dock changing their appearance, more specifically by donning a pair of glasses.

It’s a serious tactic too. In 2012, a defendant’s use of spectacles in trial went all the way to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals, which had to decide whether the accused’s rights were prejudiced by his being issued a “change-of-appearance” instruction following his decision to wear glasses at trial – glasses he didn’t in fact need to see properly. The court highlighted that doing just this was becoming something of a trend.

Really wearing glasses is like cosmetic surgery without the knife – it immediately changes how your character is represented

Different personalities

“Oh yes,” says Ralph Anderl, chief executive of eyewear company IC Berlin, “we can see when people in our shops try on different glasses that they’re really exploring different personalities. When we design frames, we have a personality type for them in mind.

“Really wearing glasses is like cosmetic surgery without the knife – it immediately changes how your character is represented and all the more so because they’re located at the most important part of the body in terms of non-verbal communication. That’s why blocking the eyes with sunglasses suggests mystery and cool.”

“Really wearing glasses is like cosmetic surgery without the knife – it immediately changes how your character is represented and all the more so because they’re located at the most important part of the body in terms of non-verbal communication. That’s why blocking the eyes with sunglasses suggests mystery and cool.”

Indeed, the aforementioned Court of Appeals case was, as the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers in the US noted, merely an acknowledgement of what we all already know that people judge a book by its cover. Moreover that perception of character can be positively skewed, in this case through the association of wearing glasses with traits such as intelligence, honesty – and a decreased propensity to commit a crime. That’s why glasses have played a part in helping individuals who, despite confession and DNA evidence, have escaped conviction and then ditched the specs the moment they were acquitted.

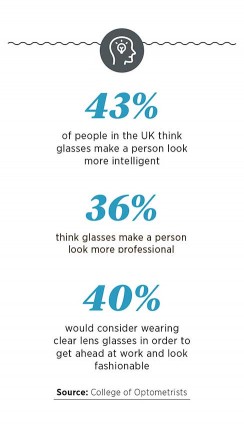

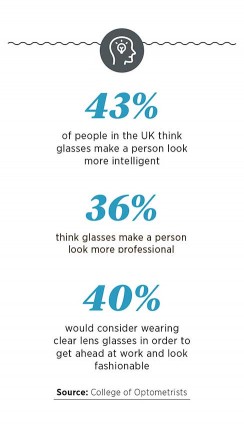

It has probably helped a few get new jobs too. A 2013 study found that, all other things being equal, job hunters were more likely to get hired if they wore glasses to their interview. “The connection between glasses and intellectualism is unconscious and metaphoric,” says Cary Cooper, professor of occupational psychology at Lancaster University. “The idea is that people who wear glasses must read a lot – much as dark glasses, of course, suggest secrecy or introversion, which is why celebrities wear them to shield their identity.”

Indeed, research has indicated that there may be a real, genetic link between myopia and intelligence.

“I wear glasses though I can’t say I know anyone has made assumptions about me because of them,” Professor Cooper adds. “But then I also have a beard, which has strong connotations too. These kind of quick visual assessments are only a short-cut to making a first connection with someone; after that the impression is quickly confirmed or countered by other information.”

First impressions count

Still, first impressions count, as they say. Perhaps this is why a 2011 study by the US Vision Council estimated that some 16 million Americans wore non-prescription glasses for the purpose of changing their appearance. And small wonder given how deeply ingrained the associations between being smart and wearing glasses is. Another study, this time in west London, found that children as young as eight make the connection, one which only strengthens with age. The older a child gets, right up to college age, the more likely they are, when asked to draw a scientist, to depict someone in glasses.

Nor is the association a new one. Glasses may have only crossed the line from crutch to cool during the late-1950s and 1960s, in large part thanks to the likes of Michael Caine, Peter Sellers and Buddy Holly wearing their glasses publicly. Rock’n’roll star Holly performed almost blind for years before his manager suggested wearing his specs could actually enhance his image. But a Purdue University study conducted in 1944 had already found that people who wore glasses, both men and women alike, were considered more industrious, dependable and intelligent.

[embed_related]

Such a correlation is only reinforced by popular culture, from novels to Hollywood. These, as we all do, trade in the useful, if not always accurate, economy of stereotype. And a stereotype it is – and not always a positive one either. Although studies have shown a connection between wearing glasses and being perceived as more intelligent, donning specs may also be seen as less attractive. This can even come down to the style of glasses worn as a 2011 study co-authored by Helmut Leder, professor of psychology at the University of Vienna and an expert in “face processing” research, found that rimless glasses retain all the beneficial associations, but have no negative impact on perceived attractiveness.

“Stereotypes are always in flux,” says Professor Leder, “and my feeling is that the negative stereotype of glasses doesn’t really apply now. The eyewear industry is so professional and lucrative that it has worked hard to ensure not many people now wear glasses who don’t really suit them. But I do think the association with intellectualism still holds true and will continue to, although there is the potential for that to break down as more and more people wear glasses.

“Times were when people who wore very strong spectacle shapes were all thought to be German, while very conservative traditional styles made you British. Globalisation has broken down those kind of national stereotypes, but it shows how loaded with meaning glasses can be.”

A psychological tool

They can be loaded with memory too. In a competitive world, glasses can also prove a psychological tool in making their wearers more distinctive, even though tests have shown that wearing specs actually slows down the speed with which someone can distinguish between you and another specs wearer. Glasses can be a potent form of personal branding – consider Woody Allen, Le Corbusier, Yves Saint Laurent, John Lennon or Gandhi, whose glasses fetched £1.27 million at auction a few years ago. It’s branding that is especially useful in business – the likes of Apple’s Steve Jobs, Juergen Schrempp, former chief executive of DaimlerChrysler, and Google’s one-time chief executive Eric Schmidt all knew how glasses were part, so to speak, of their leadership package.

“You recognise some people for their choice of eyewear and I know some people will even change styles to suit the environment they’re in, whether that’s business-like, creative or more social,” says Jason Kirk, founder of Kirk & Kirk eyewear. “At one point not that long ago, it was hard to get people in the public eye to wear glasses at all. It was perceived as a sign of frailty. But it’s remarkable the number of people who now just see non-prescription glasses as another accessory, as a means of manipulating their image, regardless of any medical need.”

Mr Kirk adds: “It’s not just a matter of how glasses shape perception of you. It’s about how wearing glasses shapes your own psychology. People now even wear glasses as a kind of power play, as an expression of confidence, for example, or to boost their confidence.” And with good reason. A study conducted during the 1980s had subjects take intelligence tests, both wearing glasses and without them. It found that while wearing glasses didn’t actually improve their scores, it did make the subjects believe they had performed better.

Clearly spectacles are about much more than correcting eyesight. Increasingly, to don frames is to enter a two-way stream of subliminal, and sometimes not so subliminal, perception. Not that it always works in your favour. Pol Pot, lest we forget, singled out people wearing glasses when he wanted to rid Cambodia of potential dissidents. And consider the strange case of the five young men who went on trial in Washington DC in 2010 for first degree murder. On the advice of their lawyer, all of the defendants arrived in court wearing large-framed, heavy-rimmed glasses. Only one had ever worn glasses before. All five were found guilty.

Different personalities