Age-related macular degeneration or AMD is by far the leading cause of blindness in the UK. And with an ageing population its prevalence is certain to rise.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) reports a significant increase in hospital activity for cases of AMD from fewer than 10,000 in 2005-06 to more than 75,000 in 2013-14. The condition is thought to affect 600,000 people in the UK.

Age-related macular degeneration affects the central part of the retina, which is called the macula, and causes changes to the central vision. This is most common among people in their 80s and 90s. It does not cause total blindness but can make everyday activities like reading and recognising people’s faces difficult, which leads to a loss of independence.

Causes and cures for age-related macular degeneration still unknown

The exact cause of age-related macular degeneration is unknown. There are a number of risk factors which could increase your chances of developing the condition, such as smoking, high blood pressure, being overweight and a family history of the condition.

There are two types of macular disease, known as ‘wet’ and ‘dry’. The dry variant of the disease tends to progress more slowly, while the wet variant can appear over a few weeks or months.

There’s currently no way to treat dry AMD, however there is some evidence that vitamins can help slow down disease progression in certain patients. The treatment for wet AMD available on the NHS is with a group of medications called anti- vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) drugs. These work by stopping new blood vessels from growing, preventing further damage to sight. The medicine is injected into the vitreous, the gel-like substance inside the eye.

The expected increase in patient numbers, combined with the high cost of existing treatments, has sparked significant clinical research into AMD

The first symptom is often a section of blurred or distorted vision. Other symptoms include seeing straight lines as wavy or crooked and objects looking smaller than normal. Sometimes age-related macular degeneration may be found during a routine eye test before the symptoms materialise.

Steps being made towards AMD treatment

The expected increase in patient numbers, combined with the high cost of existing treatments, means funding new research into AMD and treatments for the condition has never been more critical. Earlier this year doctors announced they had taken a significant step forward, using cells from a human embryo which were grown into a patch inserted into the back of the eye.

The macula is made up of rods and cones that sense light, and behind those are a layer of nourishing cells called the retinal pigment epithelium. When this support layer fails, it causes macular degeneration and blindness. Doctors at Moorfields Eye Hospital have devised a way to build a new retinal pigment epithelium which can be implanted into the eye.

In July promising results emerged of the effectiveness of a small, refillable eye implant, which could mean patients go several months between treatment but even if proved to be effective this implant is years away from being made available.

Meanwhile, other companies are looking at similar technology to treat wet AMD, including Regeneron which has recently begun its own sustained-release initiative for Eylea, a medication that is administered by an injection into the eye. With an ageing population, new products to prevent and treat AMD will be welcomed by many.

‘I was told I would go blind. I was shocked, absolutely shocked’

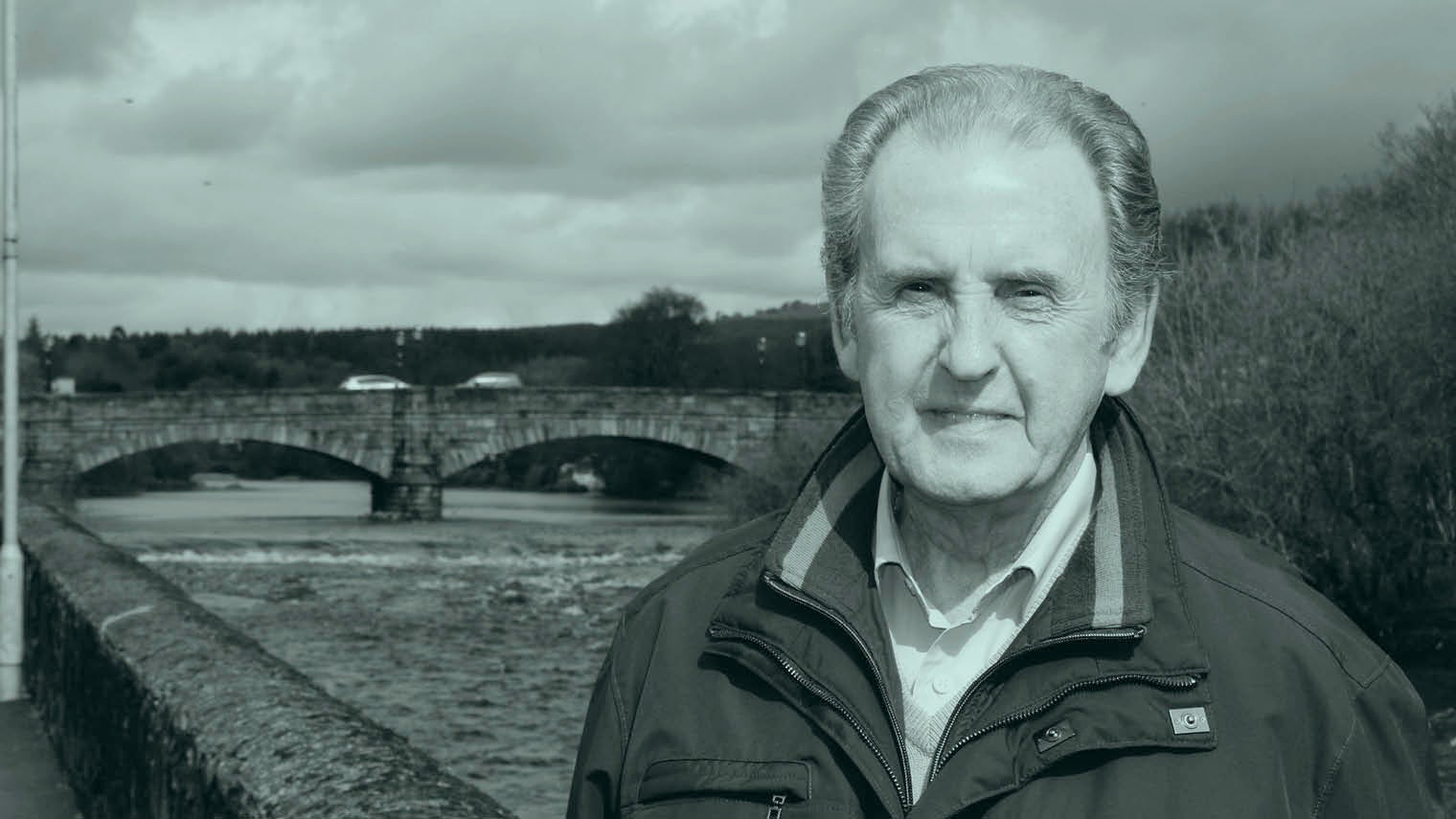

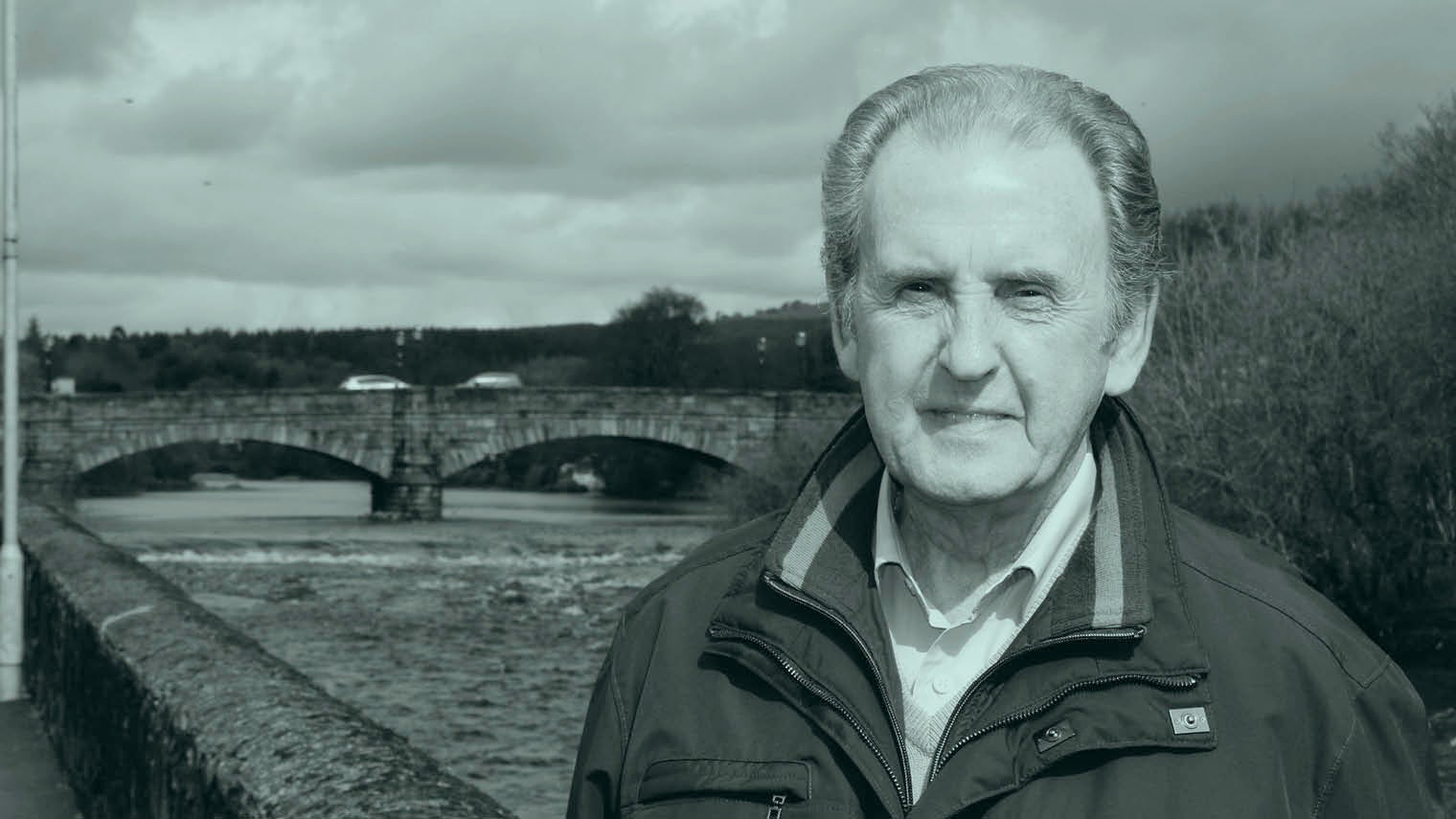

Retired police officer Charlie Bennett, 79, was a regular golfer and, at one point, a volunteer on nine different charity committees.

But this all changed in January 2013 when he went for a routine eye test and was given the devastating news that he was losing his sight to age-related macular degeneration (AMD). He was offered treatment in the form of an injection into his eye to help stabilise his condition, but it offered him little comfort.

“When I was told I needed an injection, it was my choice whether I had one. When I asked what would happen if I didn’t have it, I was told I would go blind,” he says. “I was shocked, absolutely shocked, for a number of reasons. I know now that I went into denial. I didn’t want to speak about it. I didn’t want to seek help. My wife had a hard time of it, trying to do her best to get help, but I was just digging my heels in and saying I didn’t want to do that. It was a terrible time.”

Charlie was eventually persuaded to attend a support group set up by national charity the Macular Society, for people in Dumfries and Galloway where he lives.

“That was the best thing that happened to me,” he says. “It gave me the feeling that it wasn’t the end of the world. I could contribute, I could do things. It really gave me a boost. Also, mixing with people with the same condition as you is a big benefit. That got me back on track.”

Causes and cures for age-related macular degeneration still unknown

Steps being made towards AMD treatment