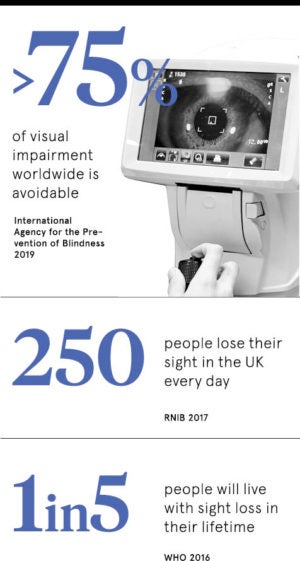

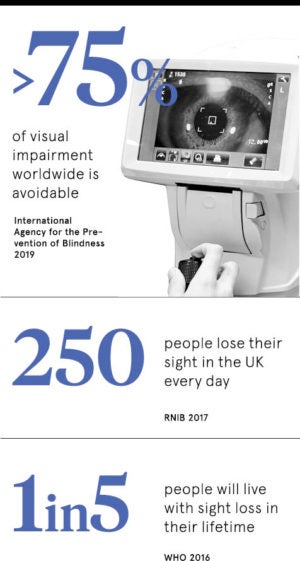

Sight, the precious sense that brings us perspective and wonder, is under unprecedented attack. Despite huge clinical and technological advances, record numbers of people are suffering from avoidable blindness.

The economic burden of sight loss has been estimated at £28.1 billion a year in the UK, yet more than 50 per cent of blindness is avoidable.

These stark statistics are made even more disturbing by the fact that, while health and longevity profiles across all disabilities are improving, sight loss is becoming worse.

People think of eye checks as a case of if you need spectacles or not, so a cultural change in understanding is needed

Research projects are bringing us bionic eyes, stem cell regrowth and artificial intelligence (AI) that can combat the ravages of eye disease. But they are ranged against formidable harbingers of darkness in obesity, outmoded systems, poor funding and ageing populations.

It is a healthcare battle of our time. The rise of type-2 diabetes has led to an alarming climb of diabetic retinopathy over the last decade and, with more than five million people predicted to have the condition by 2025, the burden can only increase.

The maelstrom’s force is accelerated by an ageing population suffering from natural sight loss and a stressed healthcare system that results in huge delays for basic sight-saving treatment and an acute shortage of ophthalmologists in training.

Diagnosis of blindness under strain

The All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Eye Health and Visual Impairment reported in June 2018 that sight loss is projected to increase by more than 10 per cent by 2020 and by 40 per cent by 2030.

Ophthalmology has the second highest outpatient attendance of any specialty with a 10 per cent increase over the last four years to almost 7.6 million appointments in 2016-17 in England, yet there is a chronic shortage of ophthalmology consultant posts.

A report from the Royal College of Ophthalmologists in 2018 warned that 67 per cent of hospital eye units were using locum doctors to fill consultant posts, an increase of 52 per cent since 2016, and that around 25 per cent of the current specialist workforce is nearing retirement.

Lack of provision has a cascade impact on health and wellbeing as evidenced by APPG research, which found 70 per cent of patients felt appointment delays and cancellations caused them anxiety or stress.

“More than 50 per cent of blindness is preventable and the main causes are disease processes that could have been detected early enough to slow it down, or uncorrected short or long sight,” says Louise Gow, specialist lead for RNIB. “No one should be visually impaired because they haven’t had access to care to prescribe glasses.”

The major disease causes of blindness – diabetic retinopathy, cataracts, glaucoma, wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) – are all amenable to treatment if diagnosed early enough.

“We should be making sure that in this country people are not losing their sight when it could have been prevented,” says Ms Gow. “We have a fantastic ophthalmology service on the NHS, but it is under so much strain. Lots of patients experience delays for follow-up appointments and getting into the system, so they present with later-stage eye disease or do not even access the services and treatment they need. We need more ophthalmologists trained, and to utilise the skills of optometrists and dispensing opticians to take some of the strain from hospitals.”

Eliminating avoidable blindness

Dr Andy Cassels-Brown, medical director of the Fred Hollows Foundation, an international development agency working to eliminate avoidable blindness, underscores the need for medical and technical advances to be matched with system upgrades.

Dr Andy Cassels-Brown, medical director of the Fred Hollows Foundation, an international development agency working to eliminate avoidable blindness, underscores the need for medical and technical advances to be matched with system upgrades.

“While new technology is part of the solution to eliminating avoidable blindness, it won’t be the single solution,” he says. “Breakthroughs will also come in the form of new models of care that deliver services to more people and those most in need.

“Governments will need to oversee health systems, drive the adoption of affordable technologies and make them available to the most in need.”

The need to harness brilliant innovation with the more prosaic system design is writ large in glaucoma, a condition that slowly damages the optic nerve and erodes sight. Around 900,000 people in the UK have the condition, but public awareness is so low that around 500,000 are unaware they have it and could suffer irreversible sight loss. Regular eye tests and faster routes to treatment could turn around an insidious problem that will lead to the loss of livelihood and independence.

“The optical profession has started asking itself why enough people don’t get tested and one of the answers is for opticians to follow pharmacists in providing more services to patients and relieve the burden on GPs,” says Karen Osborn, chief executive of the International Glaucoma Association. “People understandably think of eye checks as a case of if you need spectacles or not, so a cultural change in understanding is needed because there are so many other health conditions that can be picked up.”

Exciting developments bringing new hope

It is a sobering challenge, but eye health is awash with inspiring projects that have taken bionic eyes and regenerating optic cells from hope to reality.

Professor Paulo Stanga of Manchester University has successfully implanted bionic eye systems – a prosthesis linked to a visual display unit in a pair of spectacles – to restore some functional sight to patients with retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited disease that causes blindness and AMD. Trials, funded by the NHS, are continuing and proving that a future where avoidable blindness is drastically reduced is more than just a dream.

Research is also progressing at London’s Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust to tackle the diagnostic challenge. Its collaboration with DeepMind Health, part of Google’s healthcare division, uses AI technology to detect eye conditions automatically in seconds and triage patients to the right treatment, reducing the chances of sight loss.

It claims a 94 per cent accuracy rate on eye-scan analysis and could, if clinically validated, reduce diagnosis time, release consultants for other work and create a data reservoir to improve future research.

Dr Pearse Keane, consultant ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital, says: “Our work with DeepMind Health is using artificial intelligence to detect abnormalities in patient’s eye scans. This has the potential to provide a much faster diagnosis, which is vital in preventing sight loss from a number of conditions, including age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.”

Avoidable blindness is verging on a national tragedy and it will need a concerted effort from campaigners, clinicians, scientists, and public health and government policy to ensure people can retain the gift of sight throughout their lives.

Diagnosis of blindness under strain

Eliminating avoidable blindness