The first spectacles were invented in the 13th century and their technical progress was a slow evolution driven mainly by style and fashion rather than medical need. The pace of change accelerated in the 20th century, but we are now in an unprecedented era when technology is supercharging vision.

The eyes, romantically deemed the windows of the soul, now have the potential to become high-tech powerhouses, focal points for information that goes way beyond imagery.

A vision revolution

This is the age of bionic vision and our concepts of conventional sight are about to fragment.

Nano-engineering, microprocessor speeds and medical sciences are conspiring to create a vision revolution. The advances percolate with potential to improve health conditions dramatically, enhance everyday eyesight and open access to a mother lode of data normally channelled through smartphones and tablets.

The changes will be felt across vision with eye tests becoming even more accurate, new devices treating ailments that traditionally lead to blindness and the game-changing ability of returning failing eyesight to better than 20/20 vision.

“With sight loss predicted to double by the year 2050, it is vital we explore the use of cutting-edge technology to prevent eye disease. Technology has the potential to revolutionise the way we detect and treat common eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration and glaucoma,” says Professor Sir Peng Tee Khaw, director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre in Ophthalmology at Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, who has raised more than £100 million for research.

Nano-engineering, microprocessor speeds and medical sciences are conspiring to create a vision revolution

The big players are fully enrolled with Google, Samsung and Sony investing heavily. They are matched by a small army of startups with the creative flair to address niche eye conditions and pressure points in healthcare systems.

Google’s DeepMind healthcare analytics has just announced a collaboration with Moorfields, which will supply one million anonymised eye scans potentially to train artificial intelligence systems to speed up diagnoses.

Some projects are prototypes with huge logistical hurdles before they can get to public use, but the promise for patients is already coming on stream as evidenced by two other Moorfields projects: a bionic vision system that defines shapes and light for patients with barely any sight and a device to revolutionise hospital eye examinations.

Upcoming projects

Dr Pearse Keane has just won a prestigious NIHR Clinical Scientist award and a £1-million grant to develop binocular optical coherence tomography (OCT), a hand-held device that provides greater eye test resolution than CT or MRI scanning.

The unique machine allows patients to do their own preliminary tests and manage conditions without visiting a clinician; eye specialists warned earlier this year that hundreds of patients suffer irreversible sight loss because of overstretched services dealing with ten million outpatient appointments in England during 2013-14, an increase of 30 per cent in five years.

Binocular OCT could replace the traditional eye examinations of using slit-lamp biomicroscopy, which was invented in 1911, and it is being tested on patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy (DR).

DR, which is increasing in the UK by more than 25 per cent annually, can also be helped by an innovative sleep mask with 400 in-built light-emitting diodes that administer a precise dose of light through closed eyelids to stimulate the retina to repair itself.

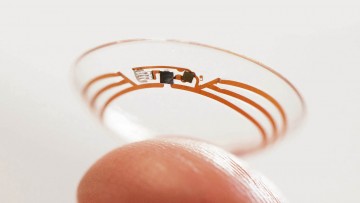

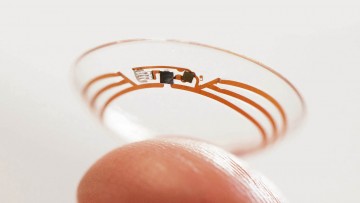

Google and Novartis are developing a smart contact lens that can detect glucose levels in tears and relay early warnings to people with diabetes

The Noctura 400, made by PolyPhotonix in Sedgefield, County Durham, is being trialled across the NHS. Paul Pritchard, of the Diabetes Forum, which helps a community of 200,000 members, comments: “Technology is playing a crucial role in the future of eye health. We face huge societal problems from DR, but tech devices such as Noctura and others are at the forefront of a new age for eye health.”

The second Moorfields project is part of a European multi-centre trial into the Iris Vision Restoration System that uses a special camera, processor pack and a retinal implant to bypass the photo processors that atrophy in a range of conditions.

A camera in a pair of goggles, linked by a lead to the processor worn on the hip, picks up movement and light, and sends commands via infra-red LED signals to an implant surgically inserted into the eye. The impulses then travel along the healthy optic nerve to create a form of vision.

“These patients have very poor vision in both eyes with barely any perception of light,” says Mahi Muqit, consultant vitreoretinal surgeon at Moorfields, who is leading the UK arm of the 18-month trial. “They have barely any vision and are completely unaware of the world so need walking aids and guide dogs. But with this, they will see outlines of objects and shapes – the frame of a door, the pavement edge, people walking by.”

Patients need intensive training to reintegrate themselves to a visual world and results can vary. “Some patients cannot even appreciate night and day, so this is a significant improvement that will promote confidence,” says Mr Muqit. “The ambition is to improve the clarity as the next generation of technology comes on stream.

“It doesn’t work for everyone and patients have to be realistic with their expectations, but the potential is for it to work very well. We are now seeing a lot of translational research move out of the labs and into trials. Retinal implants have moved quite fast in the last couple of years and now we have something that is quite amazing.”

Lenses and implants

Fighting back against debilitating conditions is the coal face of vision technology, but another strain of research is pushing the boundaries of possibilities with lenses and implants. The mundane act of manoeuvring a contact lens into position will soon seem as dated as drawing water from a well as advances mean the lens can be a one-off implant future-proofed for yet-to-be-devised technologies.

Canadian optometrist Garth Webb has already pioneered the intraocular bionic lens made from inert polymers, which can be positioned through a 2.7mm incision in the eye where it unfolds to hug the eye’s individual contours and integrate with its physiological structure within eight minutes. The results, due to be confirmed in clinical trials over the next year, are claimed as staggering with vision restored to three times “perfect”.

The bionic lens is the best eye you can get and will be an enduring improvement as it will last a lot longer than you will

Dr Webb has been refining and engineering the bionic lens since 2008 and, aside from its vision-correcting potential, the lens will be fitted with a special shield that sits on the cornea which can link with future developments to supply data and imagery. His product could be in use by 2018 with a predicted price tag of £400 to £800.

“Success is based on the underlying condition of the eye, but for some the results will be three times better than 20/20 vision,” says Vancouver-based Dr Webb. “It is the best eye you can get and will be an enduring improvement as it will last a lot longer than you will. It has been a daunting task to get this far, but the potential is exciting and I’m committed to spreading it across the world.”

He also believes his methods of harnessing the kinetic energy from eye muscle movement could be a power source for advanced functions being devised by Google, Samsung and Sony.

Google and the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Novartis are developing a lens with a special sensor that can detect minute movements in blood sugar levels and relay early warnings to diabetics. The Google Glass project, which feeds data to special glasses headsets, could also migrate to a lens within the eye in the future.

Augmented reality, where stored images can be overlaid on to real views, offers huge hope for people with deteriorating sight. Samsung has just secured a patent for a contact lens that can sync with a user’s mobile phone so photographs they take of surroundings or menus and signs can be transmitted through the lens to receptors in the brain.

The hope is that the lens will ultimately contain a tiny camera, motion sensors and transmitter so photographs can be taken and viewed with a predetermined blink of an eye.

Sony are on the same track, devising a system where the wearer’s blinks drive a series of commands to capture information that is translated into images.

These developments may be some way off, but the nano-engineering and technology are on target to create a form of sight for millions whose lives have been blighted by age, disease or accident.

A vision revolution

Upcoming projects