Every day 700 people are diagnosed with diabetes, and they enter a world where their work and social lives can be drastically altered.

The charity Diabetes UK sums up its pervasive impact with the telling phrase: “There’s never a day off.”

Although prime minister Theresa May has a ‘flash’ monitor, the vagaries of local funding have created a distressing postcode lottery

The diagnosis means a deep and enduring relationship with blood sugar levels, a metric that needs regular attention through self-management rituals.

The frequency of measurement depends on the characteristics of each person’s condition but, be it type-1 or type-2 diabetes and ten times a day or just once, the read-outs are critical and life affirming.

How blood glucose monitors have developed and changed

Physicians have long been aware of the jeopardy of high and low blood sugar levels, but the first glucose monitor was not devised until 1965, and device size and functionality only became user friendly at the turn of the millennium.

Just as clunky first-generation mobile phones have developed into sleek accessories, blood glucose monitors have been transformed into discreet pieces of kit producing near real-time readings.

Results from finger-prick blood testing and continuous monitoring are now available in seconds, enabling patients to avoid blood sugar highs and lows, and enjoy regular lifestyles.

Advances have been so rapid that there are now an estimated 72 variations available to deal with a critical aspect of diabetes management, but availability varies depending on local prescribing policy.

Commercially available glucose monitors vary in price and accuracy

The latest “flash” monitor, which automatically reads glucose levels through a needle-like sensor attached to a small patch worn on the back of the upper arm, can free patients from the pain of frequent finger-prick testing. It costs the NHS less than £1,000 a year and, although prime minister Theresa May has one, the vagaries of local funding have created a distressing postcode lottery.

All devices must meet International Organization for Standardization, or ISO, criteria which have been raised to ensure devices gave consistently high-quality readings.

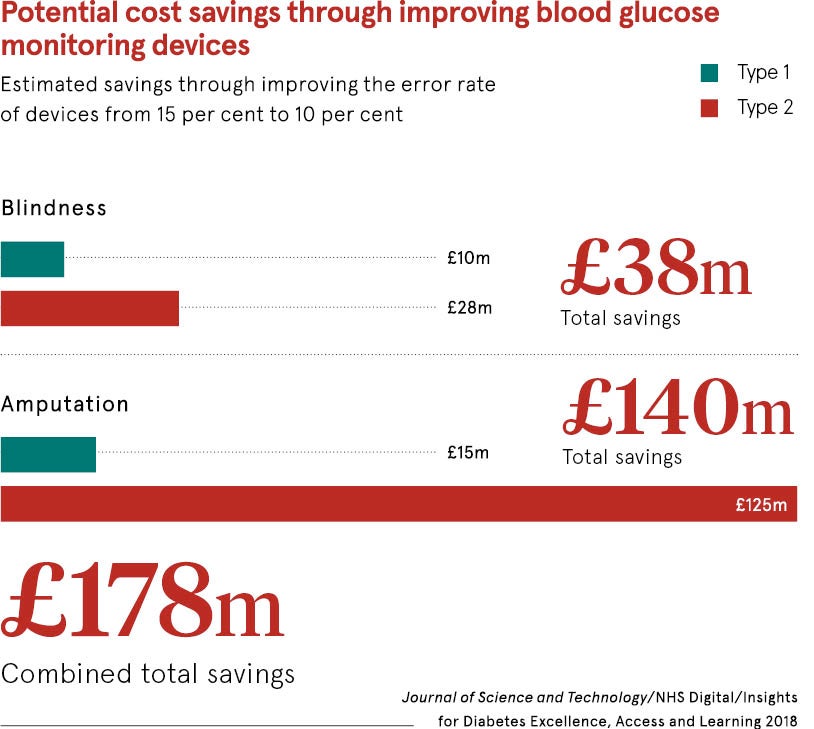

But concerns have also been raised about the robust testing of some devices with research into 17 different brands, reported in the Journal of Diabetes and Science in 2017, claiming “the accuracy of commercially available glucose monitors varies widely”.

A call for greater clarity and transparency echoes around the diabetes world and some clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) were recently accused of rationing blood glucose testing strips to save money. A survey by Diabetes UK revealed that 66 per cent of patients who responded were given no choice of blood glucose meter and had been switched to a different, cheaper meter without consultation.

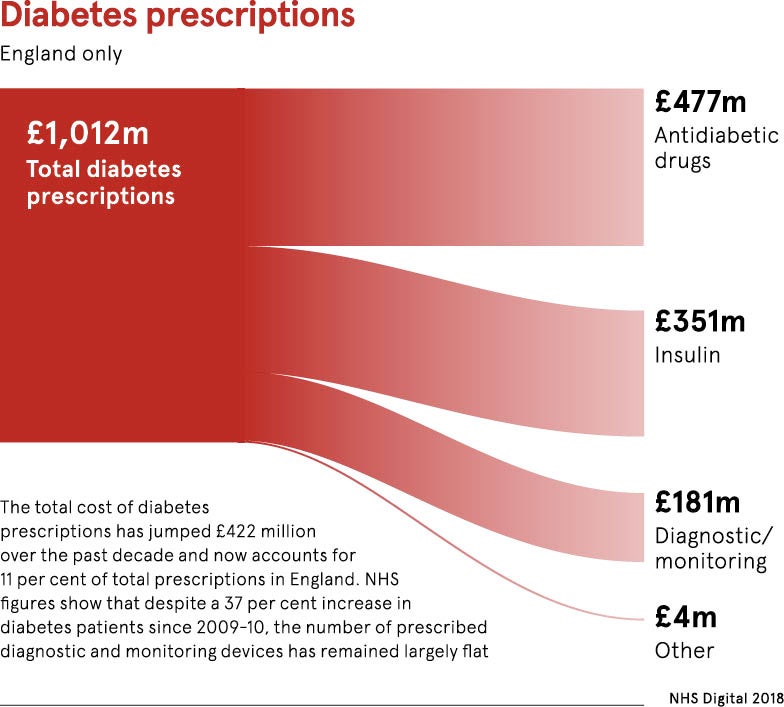

The cost of strips rose to £186.6 million, according to NHS Digital 2016 figures, and is likely to chew further into NHS budgets with the number of people with diabetes in the UK expected to rise from 3.8 million to 6.8 million within 20 years.

Blood Glucose Monitoring Guidelines, drawn up by the Training, Research and Education for Nurses in Diabetes group, note: “The prevalence of diabetes and the treatment choices for people with the condition have increased significantly in the last decade, resulting in escalating costs.”

Different glucose monitors will suit different people

The huge range of monitors can be explained by the fact that diabetes impacts in many different ways and measurements can be targeted to specific areas.

“No single glucose monitoring device will suit everyone. It’s important that there is a range of devices available locally so people can choose what best meets their needs in consultation with their doctor. However, local policies can be restrictive,” says Dan Howarth, head of care at Diabetes UK.

“Flash glucose monitoring, for example, is only available in two thirds of England, creating an unfair postcode lottery which prevents thousands of people from accessing life-changing technology, which would allow them to better manage their diabetes and reduce the risk of developing complications.”

The use of pin-pricking is still the dominant testing method and a Diabetes UK survey of 9,000 people affected by the condition revealed that 28 per cent of those surveyed encountered problems getting the medication or equipment they need to manage their diabetes, particularly test strips, pumps and continuous glucose monitoring.

Measuring clinical outcomes for patients should be priority

Dexcom, manufacturers of the G6 continuous glucose monitor, which is prescribed through secondary care, believe greater clarity is needed to ensure patients get the device that tailors to their condition.

“Clinicians have many different technology alternatives for people with diabetes, but it’s not always clear which types of systems should be used for which patients. National criteria for use and access to the different systems in different types of patients would be a good step forward towards ensuring equal access across the country,” says John Lister, Dexcom’s Europe, Middle East and Africa general manager.

“I believe that NHS and CCGs have only the best of intentions for patients. In a world of constrained budgets, I do not envy the choices they must make. However, I believe that further focus on measuring and improving clinical outcomes for patients should be prioritised, rather than focusing on cost containment, which leads to cheap solutions that frequently don’t improve outcomes.”

Philip Newland-Jones, lead pharmacist for NHS England Diabetes and Endocrinology Clinical Reference Group and a member of the Diabetes Parliamentary Think Tank, cautioned that the use of blood glucose monitors needs to be finely tuned to the individual with greater emphasis on the rationale behind testing.

“There are lots of consensus groups, but there is nothing nationally. It would be sensible to have a national recommendation on targeted testing, giving patients more information about why they should be tested,” he concludes.

How blood glucose monitors have developed and changed