The growth of human eggs from the earliest stage to full maturity outside the body has been acclaimed as a landmark development that could widen the scope of fertility treatments.

But does it offer real hope to the reported one in six UK couples with fertility problems? Expert opinion is mixed. The consensus is that it represents an important step forward, but progress in research into the most basic secrets of all – the origin and creation of life – is measured by decades rather than years.

Advances in knowledge arising from the development and study of lab-grown human eggs could help boost IVF success rates

For example, two thirds of women under 35 undergoing in vitro fertilisation will not have a baby after their treatment cycles, even though it is 40 years ago this year since the birth of Louise Brown, the world’s first test tube baby. Specialists don’t know why most IVF treatment cycles fail, but advances in knowledge arising from the development and study of lab-grown human eggs could help boost IVF success rates.

IVF success rates may be disappointing but, thanks to ongoing research, they are about 85 per cent better than in I991 when the Human and Fertilisation Embryology Authority (HFEA) started keeping records.

Transforming lab-grown human eggs into viable treatments could follow a similar pattern; the research programme started more than 30 years ago and has produced live offspring from lab-grown mice eggs.

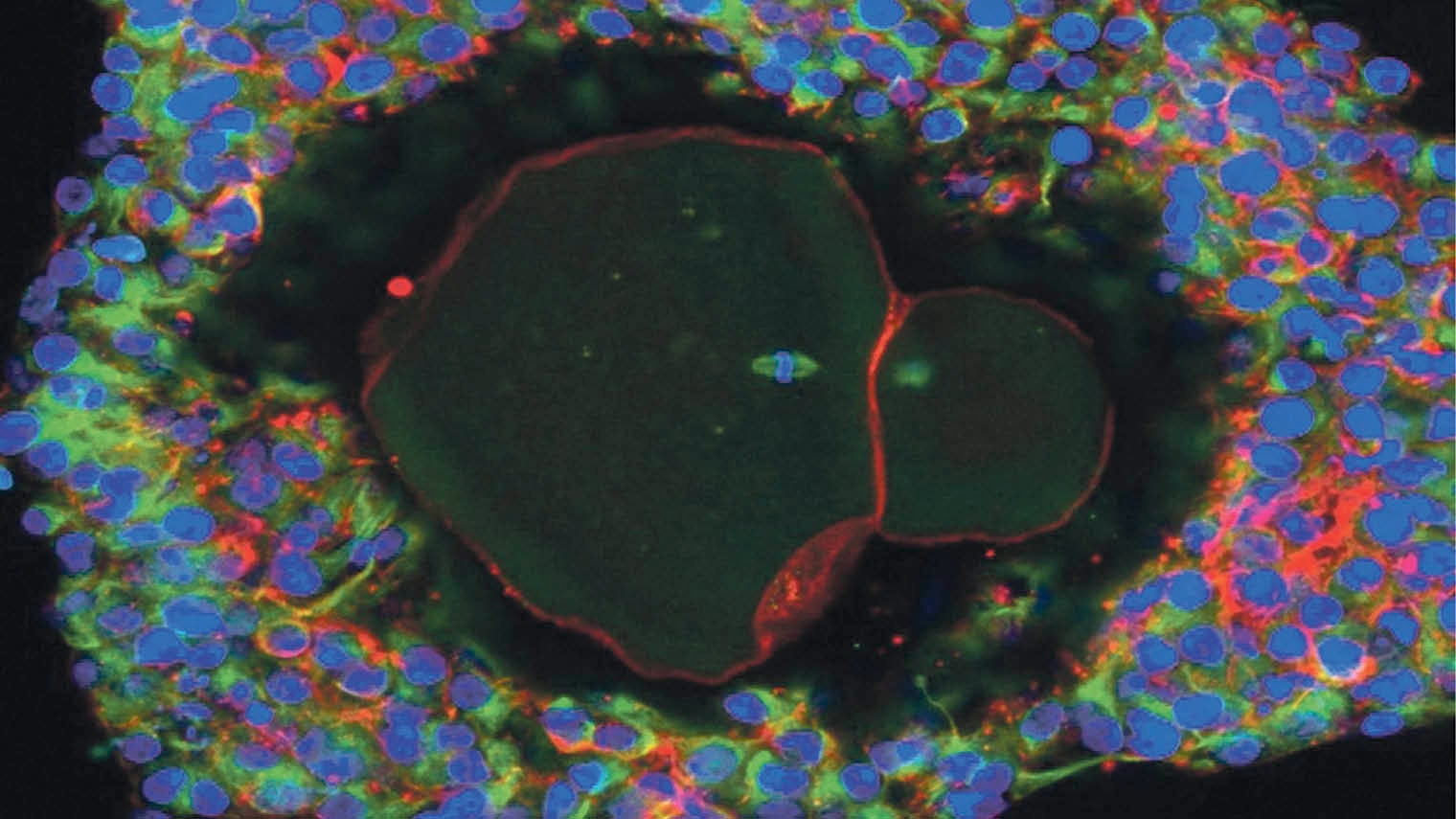

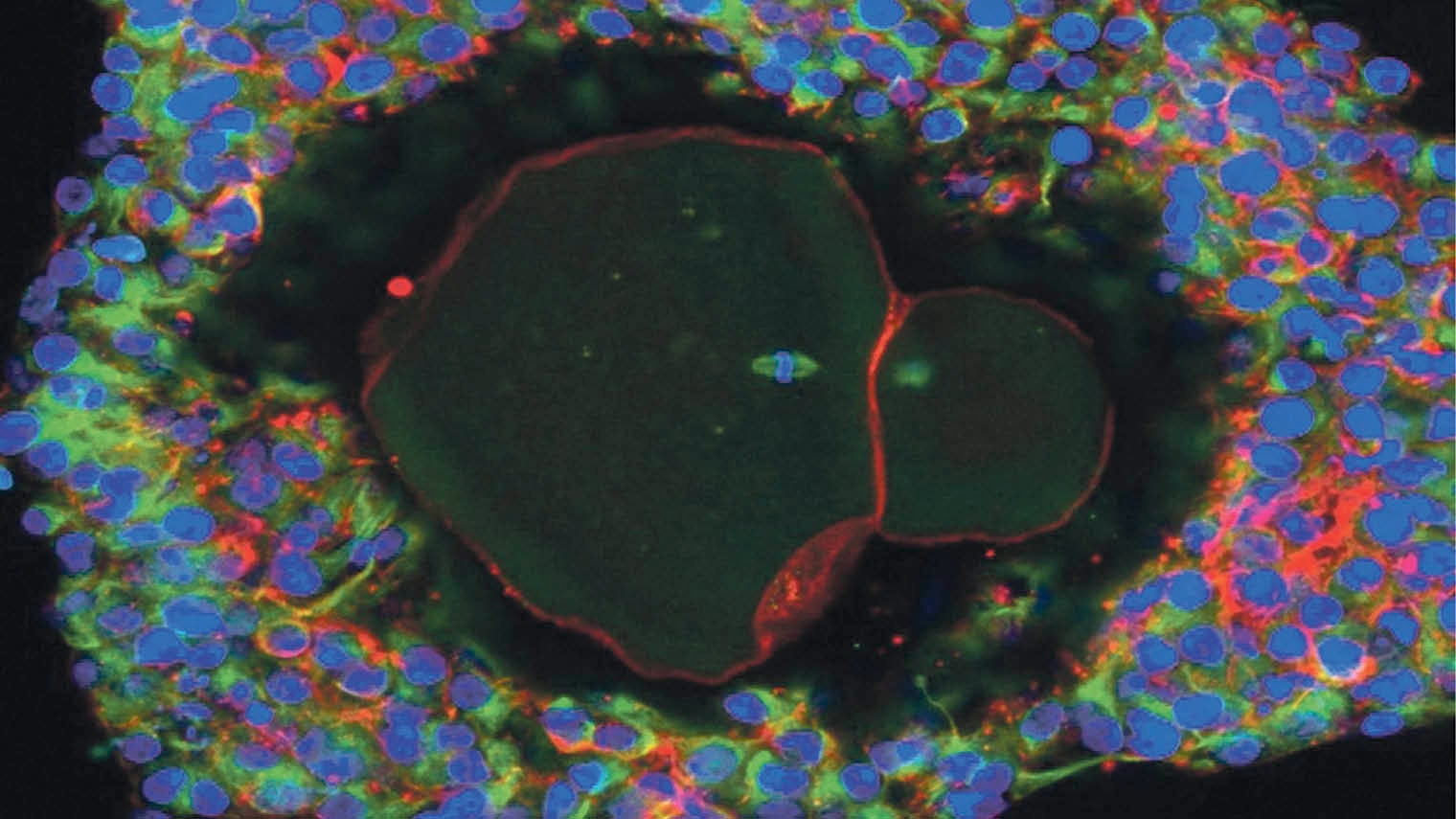

Magnification of a lab-grown, fully matured human egg ready for fertilisation

The latest work was carried out by Professor Evelyn Telfer and colleagues at Edinburgh University, the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, and the New York Center for Human Reproduction. The eggs were grown from ovarian tissue donated by ten women undergoing caesarian-section births.

Reported in the journal Molecular Human Reproduction, the research has provoked critical questions. For example, why did some of the developed eggs mature in just 22 days, compared with the five months it would have taken in the body? And why did only 10 per cent of the eggs reach full maturity?

Challenging the idea that maturation of lab-made eggs should mimic that of the natural cycle, Professor Telfer says: “The process takes much longer in the body because eggs have to work in tandem with a woman’s hormonal cycle – there are lots of control mechanisms in the body.

“We prefer to describe the way eggs grow outside the body in our system not as accelerated development, but rather as development without brakes. That’s a big difference. Logically there is no reason why it should take human eggs months to mature.

“The real problem is the basic lack of knowledge about human eggs. We speak about lack of progress in IVF in the last 40 years. This is because we lack a fundamental understanding of human egg development. It’s only this kind of work that will give us the kind of insight we need.”

Professor Telfer also dismisses the criticism that only 10 per cent of eggs in the study reached full maturity. “In the human body, only 0.1 per cent reach full maturity – 99.9 per cent degenerate – so what we are doing in our in vitro system in the laboratory is circumventing what happens in nature.”

With her colleagues, she is now planning to develop better quality eggs and to use IVF to fertilise them with sperm to test their viability; a procedure the HFEA will have to authorise. A big challenge is to create a receptive laboratory environment. Natural growth and development of eggs and the follicles or sacs containing them is controlled by the release of changing concentrations of hormones and a soup of growth-promoting nutrients.

Professor Telfer says: “We’re working on some ideas to change the lab environment. We’re on the path. We’re not where we need to be yet, but I’m confident we’ll get there.”

Patience and determination is essential. It took Sir Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe more than ten years and 467 attempts at IVF before Louise Brown became the world’s first test tube baby in 1978.

The Edinburgh research could help cancer patients. Stuart Lavery, consultant gynaecologist at Hammersmith Hospital’s Department of Reproductive Medicine in London, says it offers hope to women having sterilising treatment such as chemotherapy.

At present, freezing eggs or embryos before treatment can help to preserve their fertility, but this is not an option for women who require immediate therapy or for young girls. A girl’s eggs do not become viable until she starts her periods.

Ovarian tissue taken from such patients can be frozen for later preimplantation, but there is a risk in some cases of reintroducing tissue contaminated with cancer cells back into the patient. Laboratory-grown eggs would bypass the need to reimplant the tissue.

Improved treatment could also prevent financial exploitation. Ying Cheong, professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Southampton, says: “It is hugely disappointing that more than two thirds of patients who undergo an IVF cycle will not have a baby at the end of their treatment cycle. Doctors do not yet have the magic wand.

“With no scientific answers to explain the majority of the failures, many clinics resort to offering pointless, expensive add-ons to try to improve their success rate to no avail.”

This does not deter childless couples who are encouraged by the many success stories. More than 300,000 babies have been born in the UK from licensed fertility treatments since 1991. The secret to future increased success may well lie in eggs assuming shape and definition in Edinburgh.