Rarely has the fight against disease been so dramatic and unexpected, but a DIY insurgency against HIV helped infection rates plummet in the British capital last year.

Rarely has the fight against disease been so dramatic and unexpected, but a DIY insurgency against HIV helped infection rates plummet in the British capital last year.

Two websites offering advice on PrEP – pre-exposure prophylaxis or the practice of taking antiretroviral drugs to prevent contracting HIV – has helped cut infections recorded at four London sexual health clinics by 40 per cent.

While the clinics themselves offered essential support in the effort, use of PrEP among the highest group at risk from infection – sexually active gay men – has increased dramatically over the last 18 months through word of mouth and thanks to social media.

“We have created a community out of hope and created a substantial shift in the way community healthcare has been provided,” says Greg Owen, who runs the website I Want PrEP Now, which offers advice on how to buy the treatment. Mr Owen launched the site following a deluge of questions after posting on Facebook that he would be using PrEP.

PrEp explained

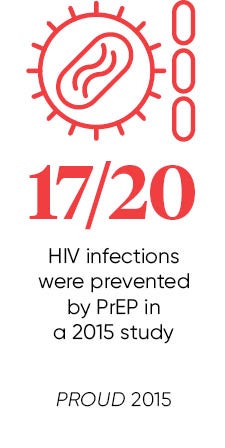

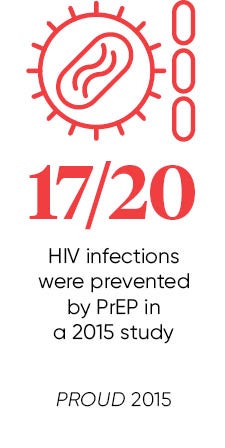

Few now question the effectiveness of PrEP in reducing the spread of HIV. One of the most-commonly cited studies, known as PROUD, showed when it was published in The Lancet that PrEP helps prevent 17 out of every 20 HIV infections. And those who did contract the virus had failed to properly adhere to the treatment, suggesting the efficacy of PrEP is closer to 100 per cent.

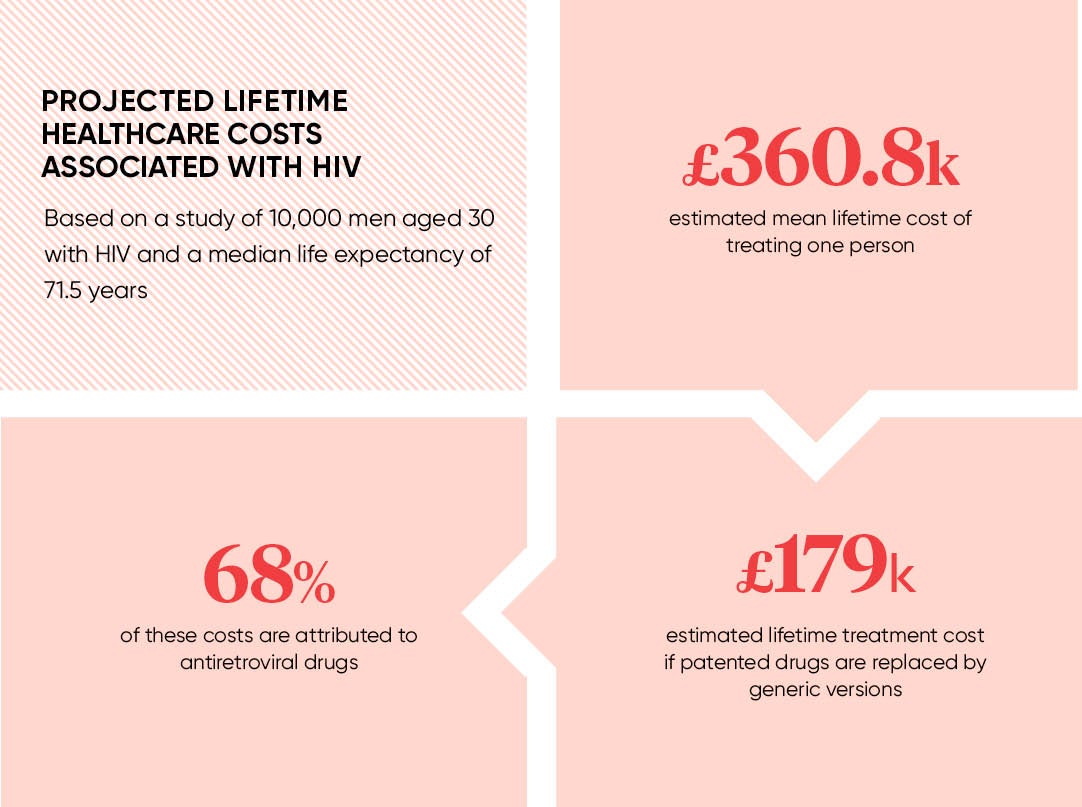

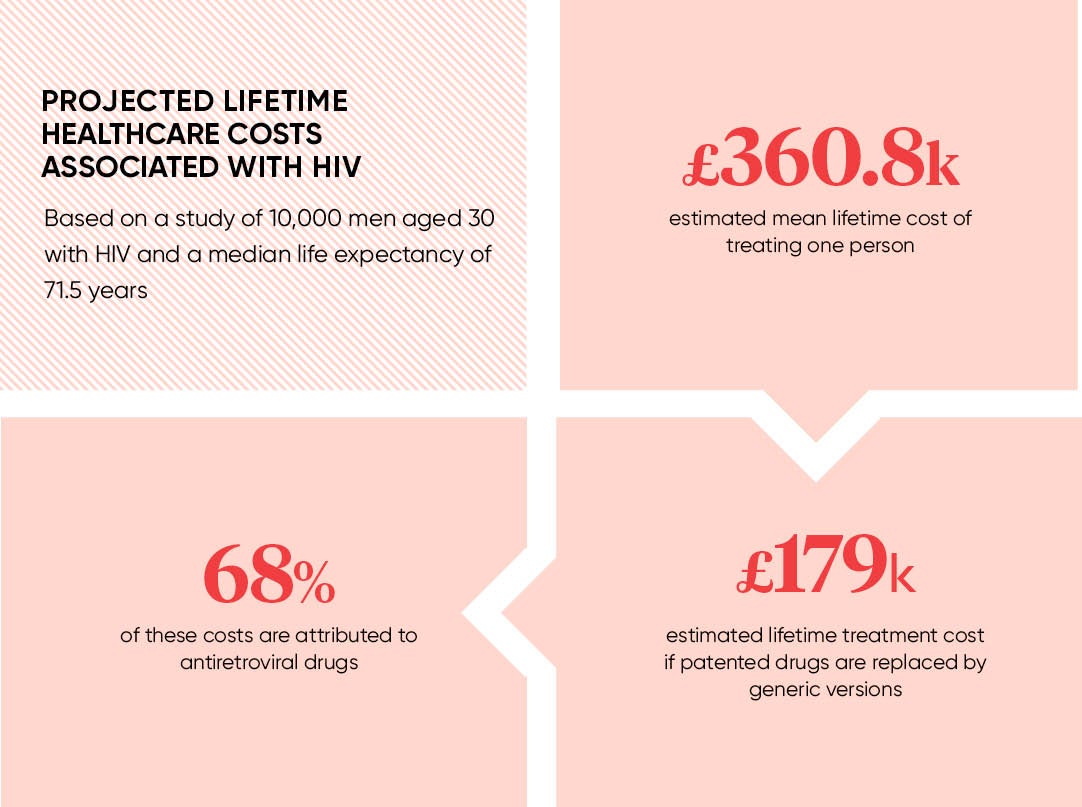

The drug most commonly used in PrEP is Truvada, which prevents HIV cells from replicating. The branded drug developed by US pharmaceutical giant Gilead costs around £400 which has proven prohibitive for many as a private prescription and has been similarly unaffordable for mass rollout by the NHS.

Mr Owen’s site, working with sexual health clinics such as 56 Dean Street in London’s Soho, has helped verify the quality of cheaper generic copies of Truvada manufactured in India and other countries in the developing world. The monthly cost for the treatment has plunged to about £40. Mr Owen says he hopes soon to be making the treatment available for as little as £20 a month to the more than 18,000 people who use his site on a monthly basis.

This is about preventing transmission, but the PrEP debate gets tainted with a special significance

Will Nutland, of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, says the effort should be seen as part of a broader set of campaigns that promote early diagnosis, access to antiretroviral drugs for those who are HIV positive as well as PrEP use.

Still, even though cities such as San Francisco, where infections dropped 17 per cent in 2015 following its Getting to Zero campaign, something different has happened in London.

“I have worked on HIV for 25 years and what we have seen with PrEP has been a massive change that I have never seen before – it’s completely unprecedented,” says Dr Nutland, who founded the PrEP advice website Prepster.

He estimates that as any as 6,000 people, some now from other European cities, are being directed from Mr Owen’s UK site to online pharmacies based overseas for PrEP.

Sheena McCormack, professor of clinical epidemiology at University College London, who led the PROUD trials, attributes the success in London to the opening of the Dean Street clinic in 2015 and the two websites that have helped make PrEP more commonplace.

“The endorsement of the clinic has been important, but the website is the one place people can go and be confident about the source of the drugs,” she says.

NHS England

But for all the successes, on average 17 people are diagnosed with HIV every day in the UK for whom PrEP is not available, according to the British HIV Association (BHIVA), a body representing those who work in HIV care.

Even Mr Owen concedes: “There is no way I can offer a wrap-around service for everyone. I love the website, but it is unsustainable in the long term.”

Unlike the United States, France, Norway, Australia, Israel, Canada, Kenya and South Africa, the UK has yet fully to approve PrEP use.

NHS Scotland announced last month that it will offer PrEP, while NHS Wales has advised against, pending a large-scale study.

But the biggest and most contested decision on whether to provide Truvada or a generic copy as a prophylactic has yet to be taken by the NHS in England, which said it would make the treatment available after losing a High Court battle. It has promised to start a trial during the summer for 10,000 people.

Chloe Orkin, who chairs BHIVA and is a consultant physician at the Royal London Hospital, says the attitude of the NHS in England has been “very disappointing”.

“We don’t need another trial. The justification for this trial is not to see whether it works, but simply to see how they should implement using PrEP,” she says.

The NHS fears that rolling out PrEP could end up costing between £10 million and £20 million a year, taking a significant chunk of its £25-million budget for new treatments against rare diseases.

Professor Orkin says decisions on which treatments are given priority are taken on grounds of effectiveness and value for money, and PrEP provides both.

“This is about preventing transmission, but the PrEP debate gets tainted with a special significance. But sex is a behaviour and we don’t hold back on other forms of preventative treatments whether it’s cervical screening or the pill,” she says. “We have a real chance to change the course of this epidemic.”

PrEp explained