New research from the University of Sheffield has highlighted nutritional support must be improved for patients living with bowel, colon and rectal cancer. Some 69 per cent of people surveyed said they had not received any diet and cancer advice or support from their healthcare team at any stage of their care, throughout diagnosis, and during and after treatment.

Treatment for colorectal cancer can involve a partial resection, or a temporary or permanent stoma, all of which affects bowel function. Consequently, most patients will encounter a number of nutritional difficulties, including being unsure what to eat and experiencing diarrhoea, constipation, appetite loss as well as changes to taste and smell.

Nutrition has a huge role to play

Research findings come as no surprise to charity Bowel Cancer UK. “Within our online community, there’s always a lot of discussion about nutrition and what to eat, and we know there is a gap in the provision of this advice,” says Lauren Wiggins, director of services at Bowel Cancer UK.

“Around 268,000 people in the UK are living with bowel cancer and that’s a lot of lives to be affected by the long-term consequences of treatment. When your bowel is affected by disease, nutrition has a huge role to play. It’s a part of the treatment and care package that is so important.”

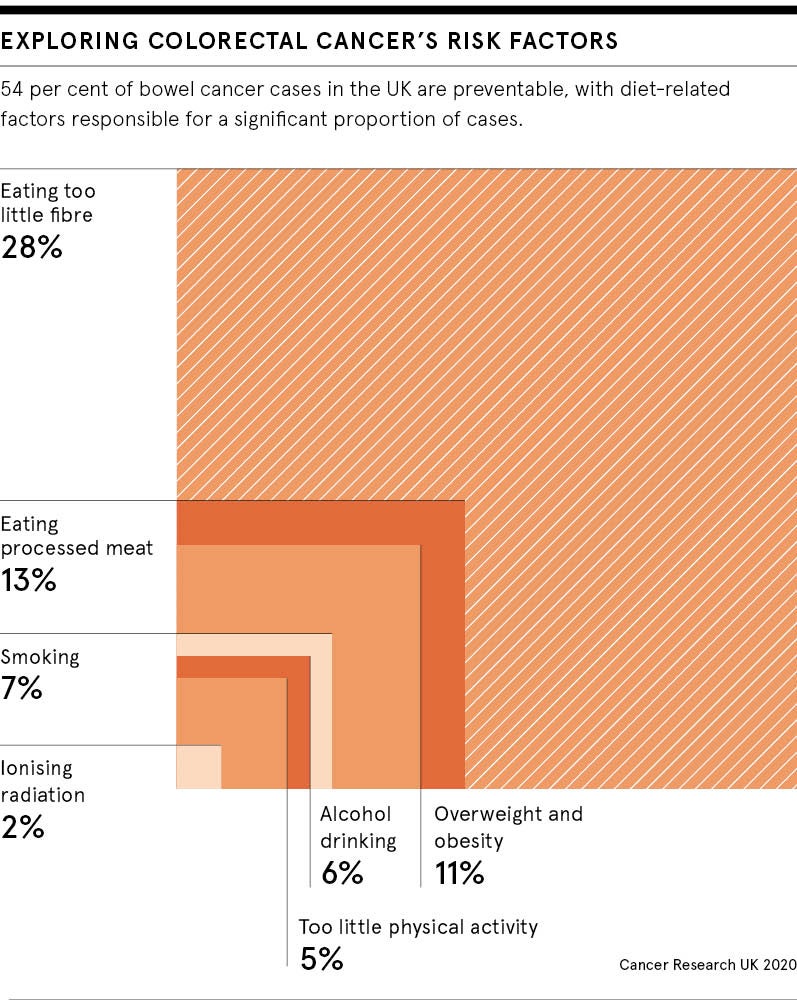

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance concurs. Its guidelines recommend colorectal cancer patients should be offered comprehensive advice on managing the effects of treatment on their bowel function. This includes information on diet, foods that can cause or contribute to bowel problems, alongside advice on weight management, physical activity and healthy lifestyle choices, such as quitting smoking and reducing alcohol consumption.

Identifying evidence-based advice online

When patients are unsure of what to eat, they tend to go online to seek advice. Bowel Cancer UK and Macmillan Cancer Support were the main sources accessed by the Sheffield University study’s respondents. Bowel Cancer UK has an Eating Well with Bowel Cancer guide and Macmillan has Eating Problems with Cancer guidance. Both are popular with people looking for evidence-based general information about diet and cancer.

“When patients look online for diet and colorectal cancer advice, the worry is they risk coming across inaccurate information,” says Dr Bernard Corfe, lead author of the study and senior lecturer in oncology at Sheffield University. “If we could introduce a kitemark or an evidence-based standard to online information, this could help people to access only reliable nutritional advice sources.”

There is an obvious need for individual advice about diet and cancer because what someone is able to eat at different stages of their treatment will change. Also, everyone is different and experiences will vary from one person to the next. For example, a young patient living with a stoma will require very different diet and lifestyle advice to an older person who has been treated for advanced bowel cancer.

Working out what you can eat

Anyone living with a long-term condition that affects the digestive system will most likely find out what foods work best for them via a process of trial and error. A food diary can help people to keep track of how they react to certain exclusions and reintroductions in their diet.

“People will ask what they should be eating and when I check whether they’ve received any advice from their healthcare team, almost everyone will say they haven’t been told anything specific,” says Kellie Anderson, nutritional adviser at Maggie’s cancer care centres. “They are just advised to eat what they fancy. For a limited number of people that might be OK. But for the vast majority, particularly when they have had colorectal surgery, they will have issues.”

While eating a balanced diet that includes lean protein, limited red meat, wholegrains and plenty of fruit and vegetables is important for our general wellbeing, and as part of cancer prevention, healthy eating can look quite different for people having treatment for colorectal cancer.

“They may need to include food in their diet that you wouldn’t describe as nutritious or as nutrient filled, but it’s good for them especially when they are recovering from surgery,” says Anderson. “This includes having white bread and rice instead of brown, ensuring the peel is removed from vegetables, excluding high-fibre foods for a short period and avoiding anything that’s spicy or too greasy.

They may need to include food that you wouldn’t describe as nutritious, but it’s good for them

“That’s why a low-fibre diet is often recommended by someone like myself and I would hope a bowel team might advise this too. The earlier the intervention is, as far as when nutritional advice is given, the better a person’s recovery is generally.”

What’s needed to improve nutritional support?

Understanding why there is disparity between the nutritional support that people receive could help to ensure it’s offered more equitably going forward.

“You may find the reasons differ depending on geographical area, the availability of local dietician services or it may be the resources are just not there,” says Wiggins at Bowel Cancer UK. “Another issue could be the resources are there, but patients don’t know about them and aren’t aware they can ask for a referral to a dietician, for example.”Corfe feels part of the problem is that nutrition is sometimes seen as a bolt-on to care. “Training and paying for enough dieticians to offer this advice to patients isn’t probably something that’s feasible within the NHS at the moment. But offering basic nutrition training through continuing professional development courses could help to improve the dietary advice provided to patients by GPs.

“There’s also a concern that there is insufficient nutrition in the medical curriculum at all stages. I think the bottom line is there needs to be more training offered to better inform GPs.”

Changing the conversation around diet and cancer

In addition, GPs could benefit from support to enable them to provide information about diet to patients living with cancer.

“We need to be giving GPs the tools to be able to have these conversations and signpost the right places where patients can get expert support,” says Wiggins.

Bringing GPs into the care pathway for colorectal cancer is important because they will be seeing those patients a lot more regularly than their hospital teams.

“The impact of treatment on the bowel is one of the longer-term consequences of treatment for this type of cancer and it can have a significant impact on a person’s quality of life. It’s vital that nutrition is addressed as part of the care pathway.”

Alternatively, general practices could create a list of evidence-based resources to provide to patients, such as information on diet and cancer from Bowel Cancer UK, Macmillan Cancer Support and Maggie’s. This would help to prevent patients coming across online diet and cancer advice from unreliable sources. Anderson also offers nutrition and cancer advice via her website Food to Glow and this resource is used by a number of hospital teams.

However, evidence-based online advice is not a substitute for a more personalised approach to how diet and nutrition advice is provided.

“The Bowel Cancer UK website has lots of information about diet, but this general information should be viewed only as a good starting point for a conversation,” says Wiggins. “It should not be considered as the end of the conversation. Tailored information is really important.”

New research from the University of Sheffield has highlighted nutritional support must be improved for patients living with bowel, colon and rectal cancer. Some 69 per cent of people surveyed said they had not received any diet and cancer advice or support from their healthcare team at any stage of their care, throughout diagnosis, and during and after treatment.

Treatment for colorectal cancer can involve a partial resection, or a temporary or permanent stoma, all of which affects bowel function. Consequently, most patients will encounter a number of nutritional difficulties, including being unsure what to eat and experiencing diarrhoea, constipation, appetite loss as well as changes to taste and smell.