Cycling home in mid-March, like many feeling depressed about the proliferating coronavirus pandemic, Tim Spector, professor of genetic epidemiology at King’s College London, suddenly had an idea.

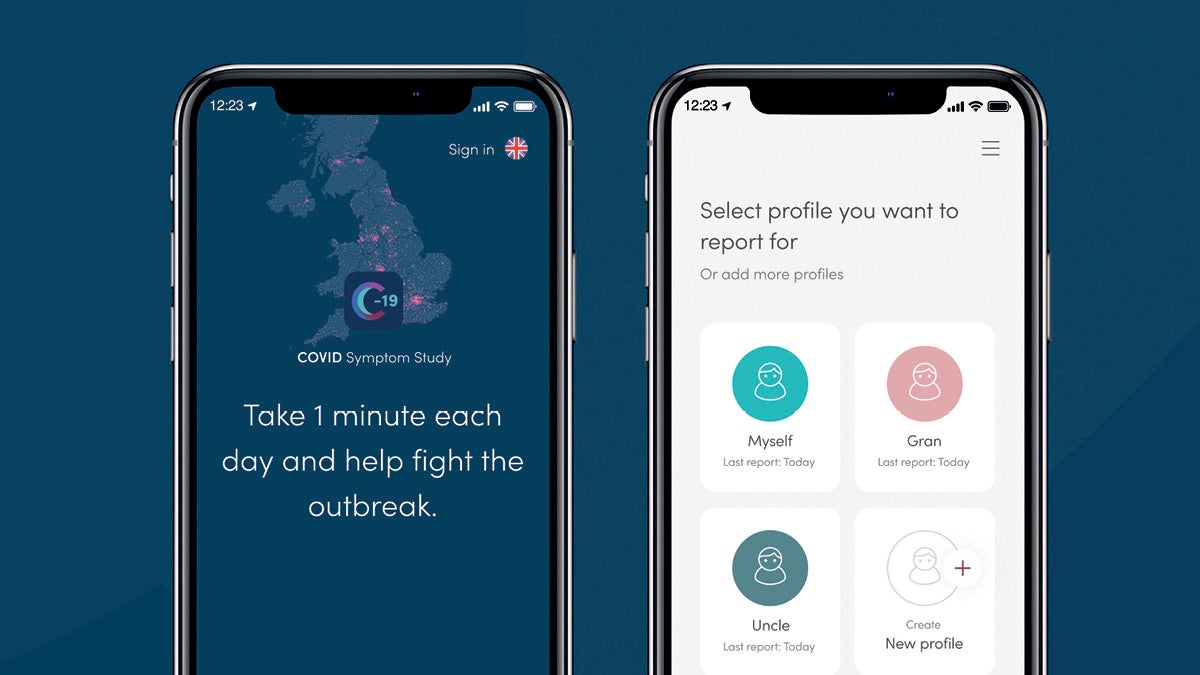

His study of more than 14,000 twins, called Twins UK, was concluding, but what if the participants were surveyed about their experience of the coronavirus? Within four days, Spector and the team behind ZOE, a personal nutritional tech company of which he is a co-founder, had expanded the idea and publicly launched the COVID Symptom Study app. In under 24 hours more than a million people were contributing. The app now has more than four million contributors and routinely monitors new cases and outbreaks.

“It’s the biggest citizen science project of its kind and has surpassed all our expectations, it’s been crucial for understanding outbreaks in the population,” says Spector.

What is a citizen scientist?

Nicholas Timpson, professor of genetic epidemiology at Bristol University, explains the citizen science concept as “getting the general public, as opposed to patients, involved in research”.

Timpson is part of another citizen science research project called Children of the 90s, which has been taking samples and surveying individuals from multiple generations for more than 30 years. In response to COVID-19, Timpson and his team are regularly questioning the participants and have noted a disproportionate impact on younger individual’s mental health compared to last year.

Though this study and the COVID Symptom Study are both citizen science based, Timpson says what is unique about the latter is the medium or channel is completely different.

“The app is very accessible; it’s a way to collect data across the population despite a really acute and difficult situation. It’s helping the public inform policy, as well as myself and other researchers to link our records to the results and combine them. It’s a remarkable thing,” he says.

Speeding up scientific research

Contributors to the COVID Symptom Study app are asked daily if they have any of 19 symptoms. Test results can also be logged and by the end of April the app had collected around 60,000, including 10,000 positive, results. The datasets were shared with researchers at King’s College London who, using machine-learning and artificial intelligence, looked at symptoms that clustered with the positive test results, against those clustered with negative results.

The information was used to train a predictive algorithm that can now determine, with an 80 per cent predictive ability, whether a person has COVID-19 depending on their symptoms. Researchers extrapolate this data across the population to create an estimated daily nationwide and local figure for people with symptomatic COVID-19.

Spector says this data allowed the researchers to understand, before the government, where outbreaks were occurring. They were also one of the first studies to identify loss of taste and smell as a key symptom of the disease, which was a significant breakthrough.

“The results are fast,” he adds. “I’ve been doing studies for 30 years and never got a result in less than six months. Yet, with the app, we included a question on loss of smell and taste, and we had the answer in a week. It’s an incredibly fast and agile tool.”

Overall, data from the app has informed 315 scientific papers and assisted the government’s testing programme by sending out 10,000 tests a week to app users over two to three months.

Combining citizen science with disruptive technology

To help manage its workload, global independent health network Cochrane, which provides systematic reviews and other synthesised research evidence to inform health decision-making, has developed a citizen science tool, called the Cochrane Crowd. Through the platform, volunteers are asked to characterise data and research. The results are fed into an algorithm to classify a record with 99 per cent accuracy.

Anna Noel-Storr, information specialist and project manager at Cochrane Crowd, says new technology combined with citizen science is disruptive.

“It has allowed us to scale; through this approach we can now handle more records than ever before and we are considering how we can change some of our other processes,” she says.

However, there are challenges, such as gaining trust within the healthcare profession and keeping participants interested.

The results are fast. I’ve been doing studies for 30 years and never got a result in less than six months

The public’s eagerness to understand COVID-19 has attracted participants to the COVID Symptom Study and been critical to its success. The researchers and app designers have encouraged this by providing regular feedback.

“I think this is why it has been much more successful than the government apps, which are one-way reporting. People like the interaction and they get used to doing it, even those who wouldn’t have before,” says Spector.

The research model could be used to derive insights on common health problems, such as obesity or diabetes, as long as “public participation is high, it’s cost effective and does not infringe on people’s personal liberties”, he adds.

What is the future of citizen science?

However, when conducting citizen science studies, it is important to be conscious that people who interact with apps, for example, are not reflective of the entire population, warns Timpson. Furthermore, maintaining public trust is paramount.

“We don’t want the Cambridge Analytica-style worry about people accessing data in an incredulous way; the notion of citizen science is far bigger than any one study, it’s a feeling that as an individual my health and my data, if combined in the right way, can contribute to better policy,” he says.

The COVID Symptom Study team are preparing to launch a school programme to monitor outbreaks in the education system, as well as research the long-term effects of COVID-19. ZOE, the platform that powers the app, is looking to launch a personal nutrition app next spring.

Timpson hopes the continued success of this research project will ultimately see citizen science attract more people.

“I want the visceral understanding the public now have of studying disease replicated outside COVID; we need to harness this opportunity to get people to understand the value of their data. If we get that right, it’ll transform how we do population science in the future,” he concludes.

Cycling home in mid-March, like many feeling depressed about the proliferating coronavirus pandemic, Tim Spector, professor of genetic epidemiology at King’s College London, suddenly had an idea.

His study of more than 14,000 twins, called Twins UK, was concluding, but what if the participants were surveyed about their experience of the coronavirus? Within four days, Spector and the team behind ZOE, a personal nutritional tech company of which he is a co-founder, had expanded the idea and publicly launched the COVID Symptom Study app. In under 24 hours more than a million people were contributing. The app now has more than four million contributors and routinely monitors new cases and outbreaks.

“It's the biggest citizen science project of its kind and has surpassed all our expectations, it’s been crucial for understanding outbreaks in the population,” says Spector.