Actors in obesity suits portrayed type-2 diabetes patients to teach German medical students about weight bias. The role-playing exercise, detailed in the BMJ Open medical journal, was designed to prompt future healthcare professionals to examine their prejudices.

Intrigued, Dr Zoe Williams, resident GP on This Morning, tried out the five-stone ensemble on the ITV programme. Afterwards, she said wearing the suit had given her a better understanding of some of the difficulties obese patients face.

They say you shouldn’t judge someone until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes. As Williams discovered, that distance feels an awful lot longer when you’re carrying 30 extra kilos. But are such initiatives, designed to increase empathy in patient care, the key to better treatment?

Doctors will shape their advice better if they can understand the patient is a person, not just someone who’s carrying a disease

Simulation suits may sound controversial, but Danielle Holmes, consultant in patient handling and founder of DFH Ergonomics, finds them valuable. She trains healthcare professionals on how to move patients with mobility problems safely to reduce the risk of injury for both parties. She uses ageing suits developed by the University of Brunel designed to induce the pain, fatigue and sensory impairment associated with later life.

“They simulate the poverty of movement as you age. It helps you understand why some elderly people can’t get out of chairs easily, which enables healthcare professionals to make better decisions when they’re with patients,” says Holmes.

She also gets her trainees to wear obesity suits, like the one Williams tried, to experience how extra weight restricts movement and comfort. And everyone is encouraged to test out the hoists and motorised beds their patients will be using. “It’s very much about knowing what patients are going to feel, so you can recommend equipment that will be most comfortable,” she explains.

Exploring implicit bias in healthcare

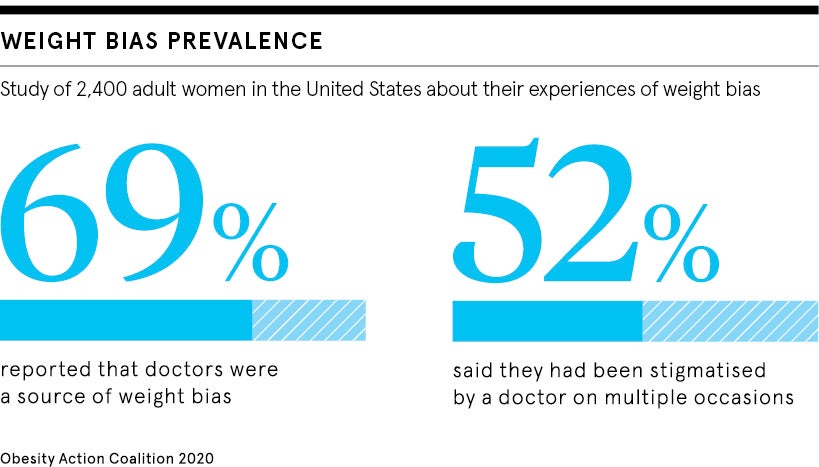

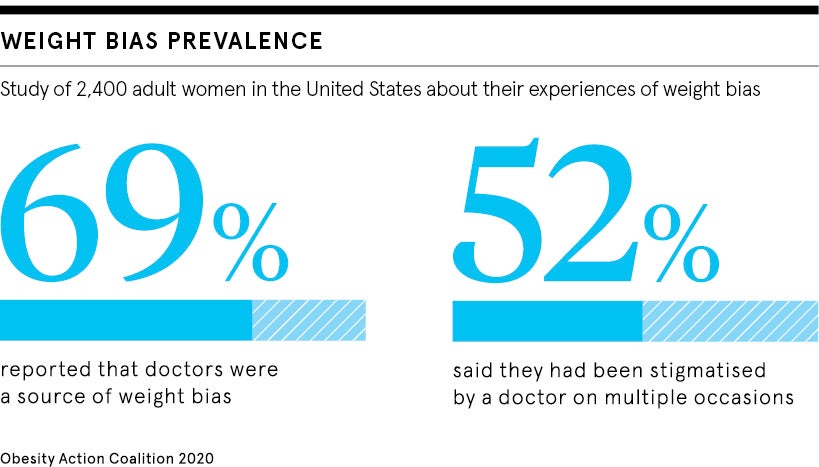

A US study of more than two thousand doctors found weight stigma is pervasive among clinicians. This can make it harder for obese people to receive good treatment compared to those with a lower body mass index.

Chloë Fitzgerald, researcher at the University of Geneva, says it’s an example of implicit bias, where we make unconscious associations about a certain group.

“When I think of salt, I automatically think of pepper. When we think of someone who’s obese, we might associate them with being lazy or weak willed,” she explains, even if these associations are not grounded in truth. Often these involuntary biases don’t even align with our perceived beliefs.

It’s not only obese patients who experience poor care. Research has shown someone’s race, age or gender can influence the standard of medical treatment received. One study found women with acute pain are less likely to be given opioid painkillers compared to men. While black women in the UK are five times more likely to die from complications in pregnancy and childbirth than white women, according to the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths.

Implicit bias can be measured using a tool called the implicit association test, but it remains a hard phenomenon to tackle, says Fitzgerald. A focus on empathy in patient care could help though. Multiple studies have found patients of doctors who are more empathetic have better outcomes and fewer complications.

“Sometimes people see empathy as pitying someone. But empathy is a broader feeling about being able to understand that person’s perspective without giving up your ability to maintain some professional detachment as well,” explains Suzanne Wood, improvement fellow at the Health Foundation.

Professor Sir Denis Pereira Gray, former president of the Royal College of General Practitioners, believes anything that can be done to illuminate empathy in patient care is worth trying.

“What I teach is that the good GP goes to great trouble to try to understand the context of his or her patient’s life. And that they will be better doctors and shape their advice better if they can understand the patient is a person, not just someone who’s carrying a particular disease,” he says.

Continuity key to patient satisfaction

While there clearly isn’t the equivalent of a bariatric suit for every vulnerable patient group, Sir Denis feels strongly that continuity of care can increase empathy. This is when a patient consistently sees the same healthcare professional so they build up a relationship. Continuity is associated with increased patient satisfaction and greater adherence to medical advice.

“It’s much easier to have empathy for a patient you’ve got to know than with a stranger,” he says. “And if patients think the doctor has understood them, they are more likely to take their advice.”

But the patient-doctor relationship goes both ways. And a major obstacle to empathy in patient care is burnout. In 2018, the Society of Occupational Medicine estimated that up to 40 per cent of UK doctors are experiencing work-related stress, with GPs reported to be most at risk. There are also severe staff shortages across the NHS.

“If a doctor has too many patients to see and is just swamped, I don’t think they can be empathic when they’re forced to work like a conveyor belt to get through,” says Sir Denis.

In 2016, the Health Foundation developed the immersive exhibition A Mile in My Shoes, a series of audio stories from people working in medicine and social care, to help the public better understand the pressures healthcare workers are experiencing. That’s not to say Wood thinks the emphasis on empathy in patient care is misplaced. A person-centred approach has never been more important given the challenges in the health service, she says, and it’s crucial this message is infused throughout medical education.

“Empathy shouldn’t be seen as an extra thing a medical student has to learn, but a fundamental part of what being a doctor is,” Wood concludes.

Exploring implicit bias in healthcare