Every day across the globe companies are violating employee’s biological clocks. The human right to a good night’s sleep isn’t enshrined in any United Nations declaration and no worker is striking on the streets of London, Tokyo or New York demanding businesses respect their circadian rhythms. Yet every hour someone, somewhere is falling asleep at a desk, in a work vehicle or on the shop floor.

This is alarming when there’s a growing body of scientific evidence that clearly demonstrates that for many the working day is out of sync with their body clocks. Not all of us are biologically programmed to function optimally from 9 to 5 or 8 to 4; some are early risers, so-called larks, others work better later in the day, so-called night owls. Yet flexible working is extremely patchy at best.

“Look at the awareness around smoking and health, and how societies worldwide have dealt with reducing it effectively; the coolness of smoking has been neutralised. A lack of sleep is not cool and like smoking we need to deal with this for the sake of people’s health; it’s a new battle line,” explains Professor Till Roenneberg, a chronobiologist at Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich.

How sleeping better could help your organisation

“If you let people sleep within their own sleep windows and work during their optimal times, you could potentially shorten their working hours by 30 per cent; with better sleep patterns people can be more productive.”

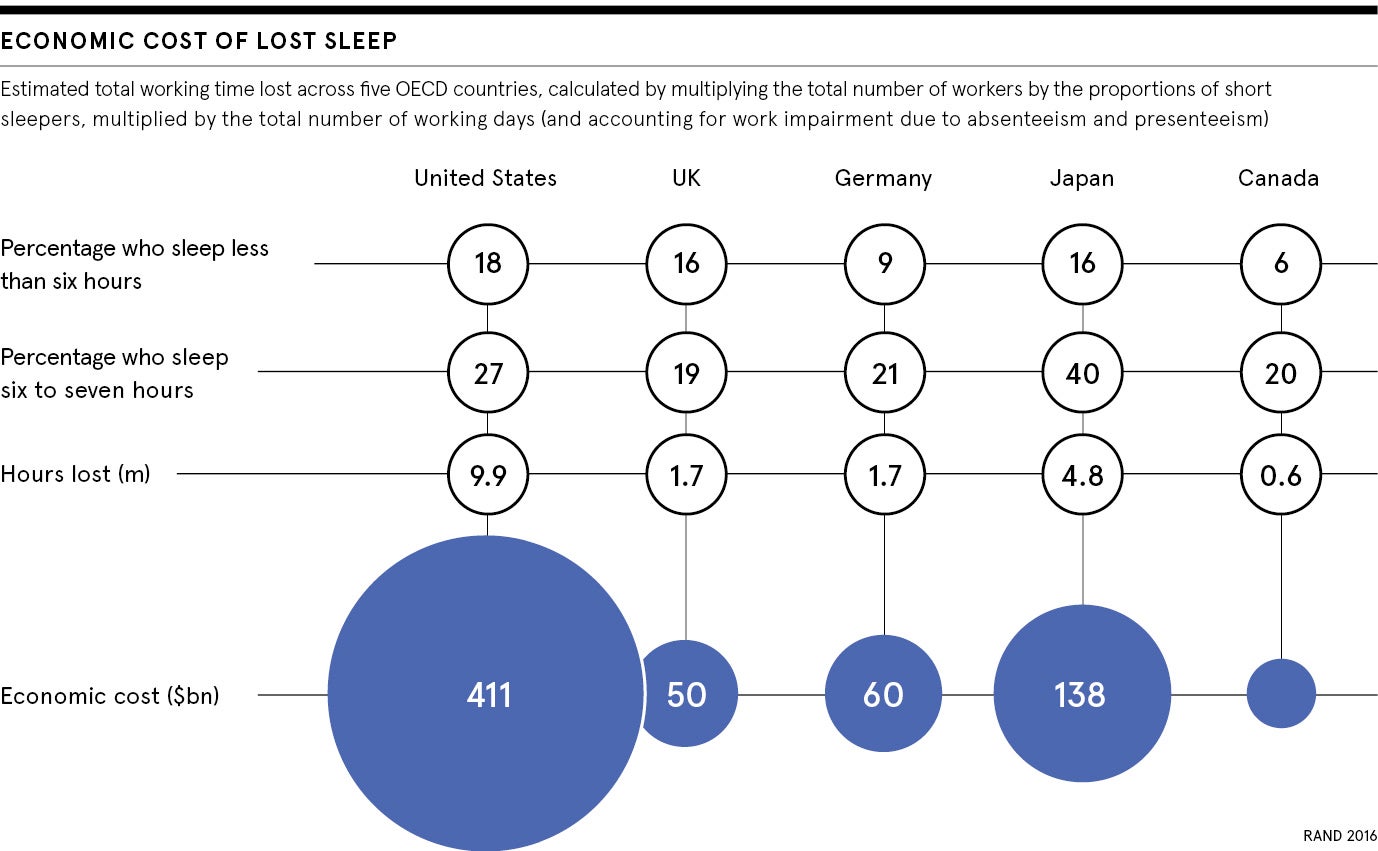

Not getting enough shut-eye has a financial burden too. It is estimated that between 1 and 3 per cent of GDP is lost due to lack of sleep, according to research from RAND Corporation. Then there’s the higher mortality risk and loss of output, depending on your country and its collective issues with sleep.

The best workers are those who work their optimal hours according to their chronotype

“All human behaviours, sleep included, are shaped by cultural beliefs and practices. Changing cultural attitudes can be difficult, but more evidence and education about the importance of sleep for a healthy lifestyle will help,” says Kristen Knutson, associate professor at the Center for Circadian and Sleep Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

What firms are doing to prioritise employee sleep

Some countries, cultures and companies that value employee wellbeing over hard and fast profits are leading the way in realising the importance of human chronotypes. They recognise that larks and owls work best at different times in the day or night.

“It’s why Mediterranean countries often employ the midday siesta in response to the post-lunch increase in melatonin, so there is some flexibility around that perceived need. A number of Japanese companies use sleep pods that enable employees to have a nap during the day to maintain productivity,” explains Dr Ari Manuel, sleep consultant at the Aintree University Hospital NHS Trust, Liverpool.

Another company in Tokyo, a wedding planner called Crazy Inc, rewards employees with food vouchers if they get six or more hours’ sleep a night, calculated via a smartphone app. In Denmark, pharmaceutical company AbbVie allows employees to design work schedules around their sleep patterns. A few years ago, ThyssenKrupp Steel in Germany looked at aligning shift workers depending on whether they were either owls or larks, but laws and pay issues stymied this approach.

“Schneider trucking in the US is also a good example of a company focusing on sleep health among its employees to strengthen their bottom line,” says Professor Nathaniel Watson, co-director of the UW Medicine Sleep Center, Seattle. “Yet worker sleep health is generally an afterthought for the vast majority of industries and companies across the world.”

Why isn’t employee sleep part of wellbeing programmes?

It doesn’t help that attitudes on sleep lag behind reality. The conventional wisdom that early birds catch the proverbial worm and are considered hard working, while night owls are deemed lazy is born out of a time when farm, field and blue-collar work was the norm. Research has shown these attitudes are entrenched, depending on which culture you experience.

“There is a consistent prejudice, yet the best workers are those who work their optimal hours according to their chronotype,” says Dr Paul Kelley, honorary associate in sleep, circadian and memory neuroscience at The Open University. “The UK is fairly advanced in this regard with about 20 per cent working to their own, flexible work hours.”

With the upswell in wellbeing in the workplace and gender equality, it is surprising that sleep equality and chrono-focused working is not higher up the corporate agenda. In many cases, practicalities still get in the way. Managers and employees are expected to be present at the same place, at the same time. Some jobs are also time inflexible, such as those in healthcare, manufacturing and shift workers in light industry.

Easy steps for working with employee body clocks

“The major challenge is that the stereotype of early risers as better employees is still pervasive and thus difficult to change,” says Christopher Barnes, associate professor of management at the University of Washington. “Matching schedules to circadian rhythms can be a useful policy change to implement, even if it’s on a small scale of a given work group.”

If you can’t change the working day in your company to match your chronotypes, you can perhaps alter the times when larks and owls should meet for that most productive brainstorming get-together.

“Late morning would seem to be the best for synchronisation. The morning types are still alert and not quite at their afternoon circadian dip in alertness, while evening types will just be arriving at work,” says Professor Watson. So let’s start with the small things.

How sleeping better could help your organisation

What firms are doing to prioritise employee sleep