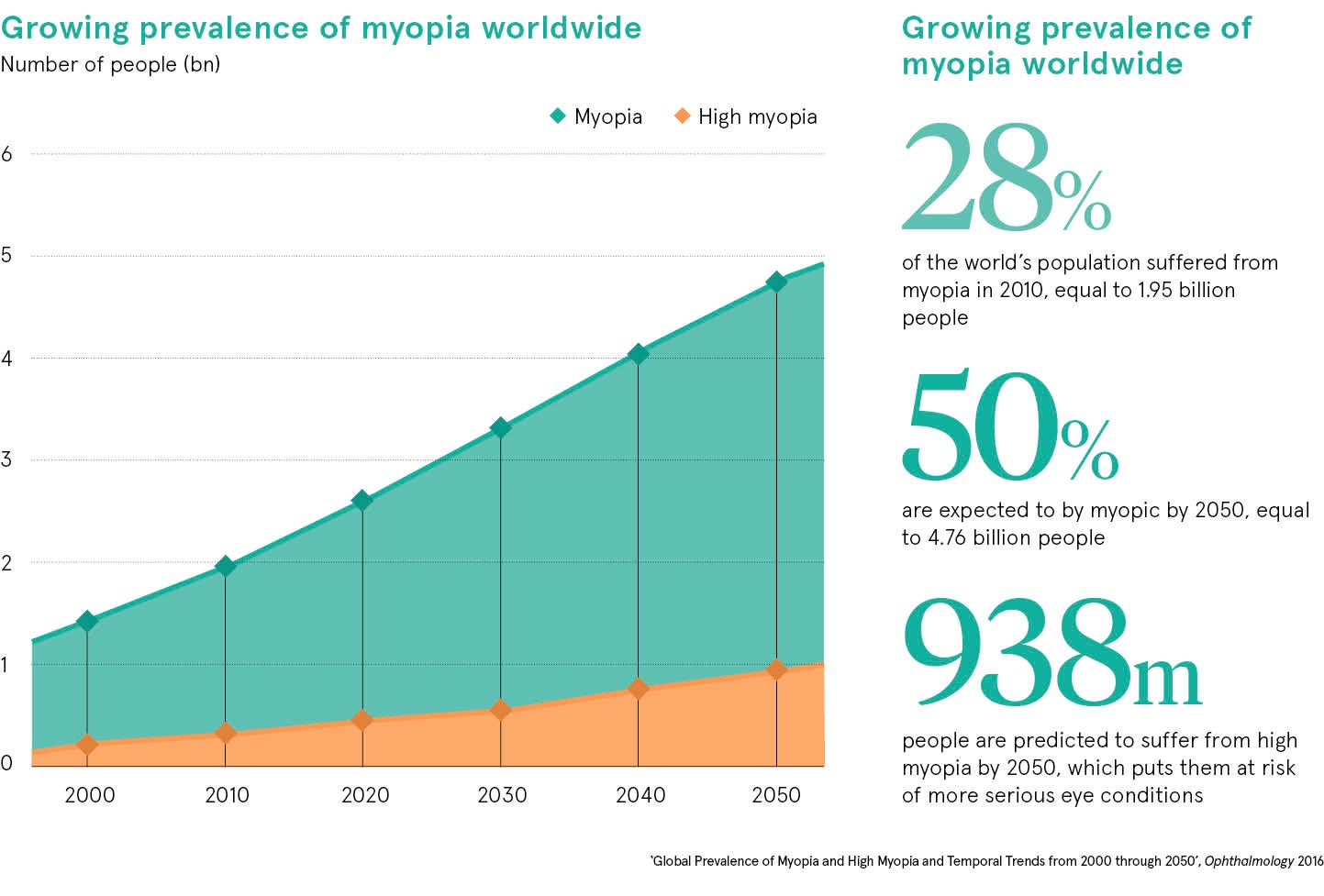

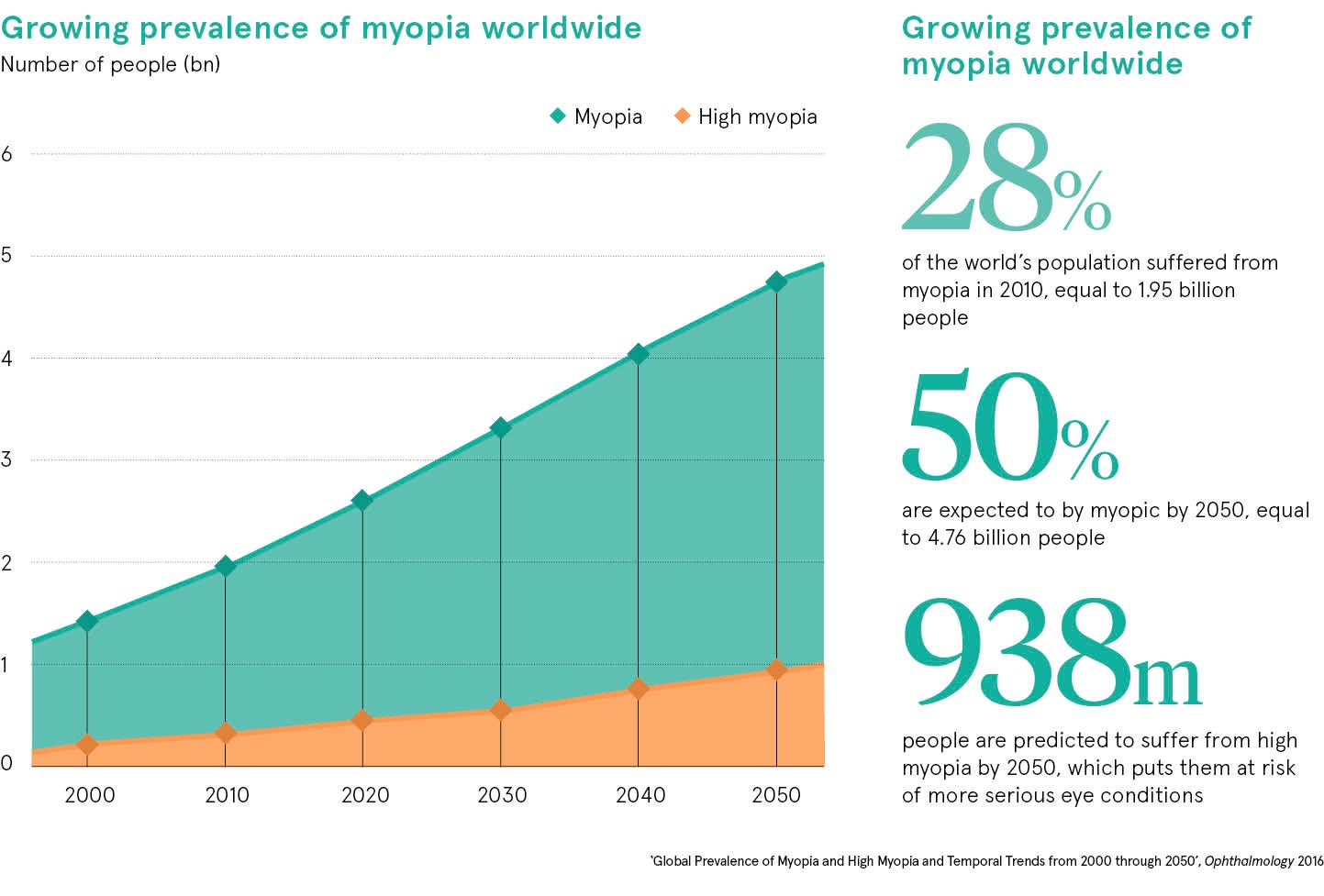

By 2050, half the world’s population – a staggering five billion people – are expected to be short-sighted compared to roughly 1.4 billion people today, according to 2016 study published in the journal Ophthalmology.

More intense education and a lack of time spent outdoors is leading to an explosion in the condition, warn experts.

“The prevalence of myopia – the medical term for short-sightedness – has risen rapidly over last few decades to a global epidemic,” warns Dr Denize Atan, consultant senior lecturer in ophthalmology at the University of Bristol. “Currently, 30 to 50 per cent of adults in the United States and Europe are myopic while, in high-income countries in East and South Eastern Asia, myopia prevalence has risen from 1 per cent to 80 or 90 per cent in school-leavers aged 17 or 18.”

This generation is set to be the most myopic the world has ever seen. We can’t simply stand by and do nothing

Myopia increases risk of more serious eye conditions

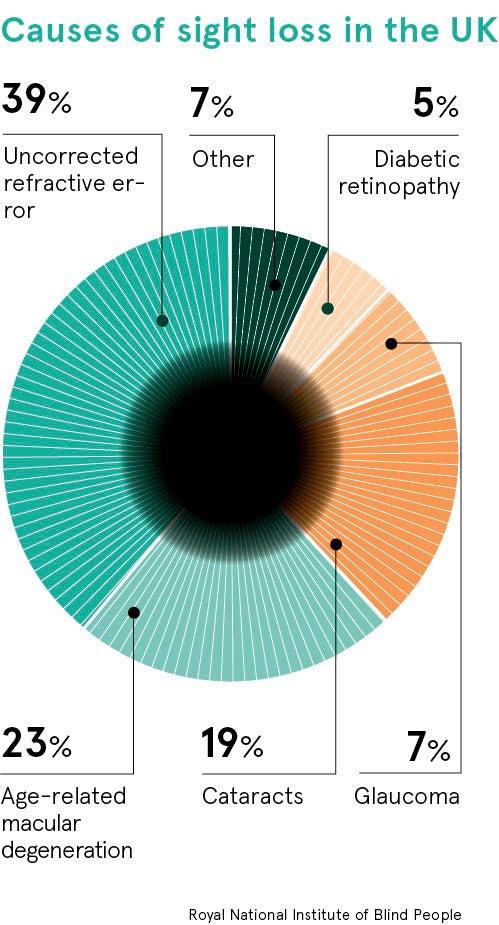

Developing myopia can mean far more than simply needing specs for distance vision. Experts warn that it can increase the risk of developing other eye conditions like myopic macular degeneration, glaucoma and retinal detachment. For the 10 per cent who develop severe myopia there is a real risk of blindness.

Someone with myopia has clear and sharply focused vision for things that are close to them but blurry vision for things that are distant from them, explains Dr Atan. “They may find it increasingly difficult to read writing on the whiteboard at school, road signs, car number plates etc unless they are close up – and might start holding books closer to their faces to read or sitting closer to the TV to see it clearly.”

There is no one definitive answer for the dramatic increase in cases, says Dr Louise Gow, specialist lead in eye health for Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB). “We know genetics is a factor; if you have a parent who is short-sighted then you are much more likely to become short-sighted,” she says.

Education major factor in myopia

Education is also a major contribution, adds Dr Atan, referring to a study led by Cardiff University and the University of Bristol she was involved in. It concluded that every year of education incrementally increases myopia to the extent that, if the average school-leaver at 16 had 20/20 vision, the average university graduate would legally need glasses to drive.

The increased intensity of educational pressures in young children has coincided with the rapid rise in myopia cases; half of children in East Asia are now myopic by the end of primary school. Because the eye continues to grow during the school years, children with early onset myopia will have much higher prescriptions and higher risk of complications from their myopia.

“Very simply, those who spend more time in education may have less exposure to natural light,” says Dr Atan. “Children need to spend more time outside. They should be encouraged to spend their break times outdoors during school hours and when not at school.”

Office workers also at greater risk of myopia

Professor Jez Guggenheim from the School of Optometry and Vision Sciences at Cardiff University, who also worked on the study, agrees. “In two randomised control trials of children aged six to 12 years old in China and Taiwan, children given 40 minutes to an hour extra outdoors each day had a reduced incidence of myopia,” he says.

It’s not just children and teenagers that are a cause for concern. New research suggests the average office worker spends almost 1,700 hours a year in front of a computer screen – the equivalent of more than 70 days. “For millions now, staring at a screen all day is the norm,” said Katie McGeechan from contact lens manufacturer ACUVUE, which commissioned the research. “However, if you look back just a few decades, far fewer of us would have spent the day looking into the same glowing rectangle, and when you add mobile phones into the mix, we’re putting our eyes through a lot every day.”

Increased screen-time is a risk, rather than screens themselves

There’s no evidence that actually using screens on devices such as computers, tablets and phones physically harms the eye, explains Dr Gow. It’s the amount of time spent on them. Official health and safety regulations stipulate that if you regularly use display screen equipment (DSE), your employer should be funding regular eye examinations and, if they reveal that you need to wear special corrective spectacles when using a visual display then your employer is obliged to pay for them. If an ordinary prescription is suitable for your DSE work, your employer doesn’t have to pay.

There is no legal guidance on screen breaks but experts advise breaking up long spells of DSE work with frequent short breaks. A five-minute break every hour is better than 20 minutes every two hours. “Eye muscles get tired when staring at a screen for any length of time because they don’t have a variety of focus,” explains Dr Gow. “Follow the 20/20/20 rule – look 20 feet away from the screen every 20 minutes, for 20 seconds – and remember to blink. We blink far less when staring at a screen – so the lubricating tear film dries out.”

Resist the urge to scroll through social media on your phone – that is, after all, just a smaller screen – and avoid collapsing in front of your TV or laptop when you get home.

Myopia has no cure, but its progress can be slowed

There is no cure for myopia but certain treatments are known to slow down the rate of progression, says Dr Atan. These include atropine eye drops in low concentrations.

“This generation is set to be the most myopic the world has ever seen. We can’t simply stand by and do nothing,” says Keith Tempany, immediate past president of the British Contact Lens Association. “Studies have shown that certain contact lenses can actually slow the progression of myopia in children by as much as 59 per cent.

“Examples include orthokeratology lenses, a rigid lens worn overnight but removed in the morning, giving the patient clear vision all day without needing to wear glasses or contact lenses. There are also soft lenses with dual focus designs, available as either daily disposables or reusables which have been shown to slow down myopic progression,” he says. “There are a raft of other lenses coming onto the market and this gives us an opportunity to make a long-lasting difference to the eye health of generations to come.”

Myopia increases risk of more serious eye conditions

Education major factor in myopia