Fertility: the “f” word so taboo that six out of ten women are more reluctant to talk about it than sexually transmitted diseases or mental health.

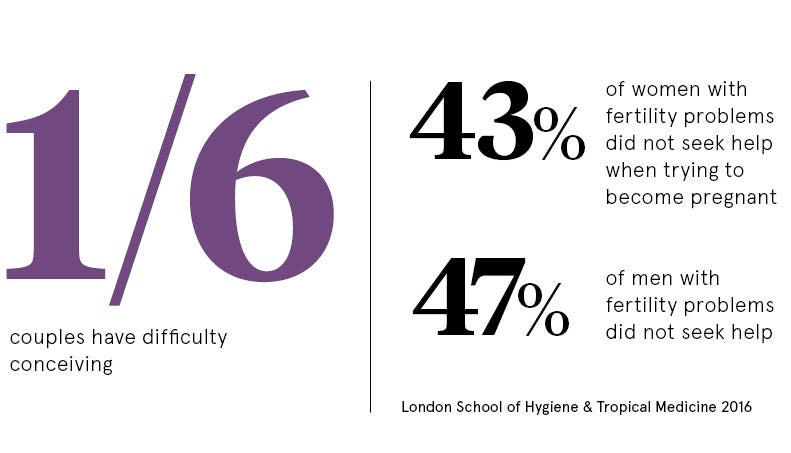

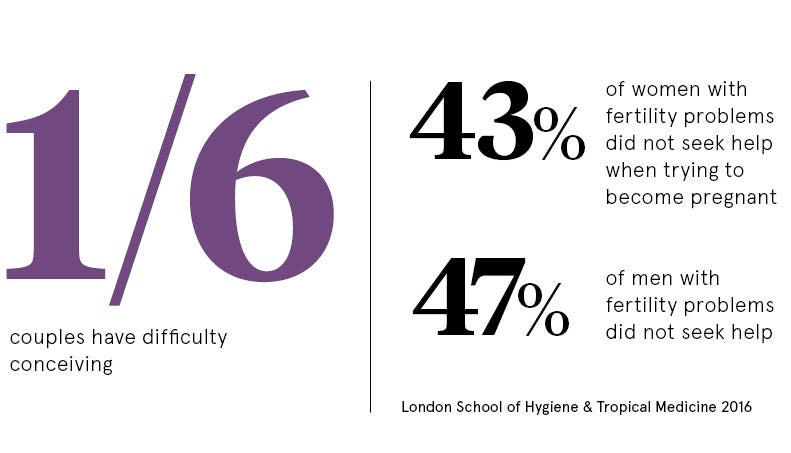

Yet 3.5 million people in the UK are affected by infertility at the same time as groundbreaking research is delivering leaps in scientific innovation.

In the 40 years since IVF was introduced, advances including gene editing, growth in reproductive medicine, egg freezing, donation and surrogacy have created a brave new fertility landscape.

But it’s not hard to see why many facing fertility challenges stay silent. Societal pressure, lack of employment support, and feelings of confusion and despair can be overwhelming.

Doctors and scientists should never forget at the heart of this are ordinary people who just want to have a family

Stigma around fertility can stem from its personal nature, says Professor Tim Child at the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

“It involves sex and reproduction, and most people assume at some point they will have children,” says Professor Child, who is the medical director at Oxford Fertility. “When that doesn’t happen, some are embarrassed, or feel a sense of failure or shame.”

Fertility Network UK chief executive Aileen Feeney adds: “There’s a huge stigma. It is so unfair that people think they can’t speak about it.”

Look at the statistics though and it’s clear the secret’s out, at least within the fertility community. More than 1.1 million IVF treatment cycles have taken place in UK licensed clinics since 1991, while at least 20,000 babies are born here each year as a result of fertility treatment, around 3 per cent of all births.

Worldwide it is estimated 6.5 million people are alive today because of IVF technology.

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), the independent regulator for the sector, believes sharing its data – like the fact that male infertility accounts for 37 per cent of IVF cycles carried out – can challenge stereotypes and shine a much-needed light on relatively new processes such as egg freezing.

Joanne Triggs, HFEA’s head of engagement, says knowledge is a powerful tool. “Our aim is to empower patients to make informed decisions and improve their chances of having a longed-for family,” she says.

While high-level data engenders transparency, it’s the grass roots that are critical in changing attitudes.

Despite running a successful podcast that has been downloaded 150,000 times in 50 countries since launching in 2014, The Fertility Podcast producer Natalie Silverman spent the first year hosting the show anonymously.

“Eventually I felt like a hypocrite discussing taboos around fertility, while not willing to share my own name,” she reveals. “Now creating a constant digital dialogue is empowering people and challenging misunderstanding.”

Education in schools has a role, with the British Fertility Society leading a task force to bring issues including future fertility on to the national curriculum.

Meanwhile, political cogs are turning and an inaugural All Party Parliamentary Group on Women’s Health, including fertility, launched last month supported by health minister Jackie Doyle-Price.

“Fertility is a fundamental aspect of our society,” says Professor Child. “More people talking about it has to be positive.”

But an honest fertility narrative is a tough ask when faced with miraculous celebrity pregnancy tales. Researchers from New York University who analysed magazines covering 240 celebrities with an average age of 35 found they contributed to misunderstanding of reproductive ageing.

Only two mentions were made of celebrities over 40 using assisted reproductive technology with their own eggs, with no mentions of donated eggs.

TV presenter Julia Bradbury has been candid about her five IVF rounds to have twin girls at 44 and explains. “The more we talk about fertility, IVF and what it means to have children for both sexes, the better,” she says. “It’s important to discuss fertility and decision-making that concerns creating a family freely and frankly in as many forums as possible, including the media, but also at home and in schools.”

With official figures showing an increasing average age of mothers – it’s 30.4 years in the UK – openness around fertility decline is evermore significant.

And while birth rates from IVF treatment have increased by around 85 per cent in the last 25 years, there are no guarantees, as a third of fertility treatment cycles result in a birth for women under 35, dipping to less than 15 per cent for those over 44.

“We are living longer, healthier lives, so people can be astounded by natural and IVF fertility rates,” says Professor Child. “Many people think being healthy and going to the gym must help, but it doesn’t help the genetic quality of eggs and sperm.”

The complexities of the fertility question can make it tricky to grasp, especially for those who have never experienced the struggle. But a new exhibition launching at the Science Museum in London on July 5 will put fertility under the spotlight for around 370,000 visitors.

The five-month showcase will not only celebrate 40 years since the birth of the first IVF baby, Louise Brown, at Oldham General Hospital, following pioneering treatment from Patrick Steptoe, Sir Robert Edwards and Jean Purdy, but also explore the ongoing negotiation between science and society around the once-fringe technology.

Connie Orbach, content developer for the Science Museum exhibition, explains: “It is important this exhibition is a catalyst for conversations around fertility.”

As the scientific world celebrates four decades of IVF contribution to reproductive health, Louise Brown emphasises the real-life impact of the sector. “I think my mum, Lesley, would be amazed at how many different techniques there are now to help both men and women with their fertility,” she says. “Almost 40 years after my birth, doctors and scientists are still doing fantastic work. They should never forget at the heart of this are ordinary people who just want to have a family.”