For many couples, the pre-pregnancy stage of fertility can be one of the most stressful periods of their lives together. The trying-to-conceive phase can create a perfect storm of pressure, with worries about potential fertility problems, lack of fertility support and a conscious lifestyle overhaul all adding to the strain.

One of the most challenging elements, however, can be the sense of isolation which comes from keeping quiet about the situation.

“At home, we talk almost obsessively about trying for a baby,” says Tom Mackenzie, 35, who has been trying for a baby with his partner for three years. “It’s such a contrast with my work life; most of my colleagues don’t even know we’re trying. I’ve stopped going to work events because I feel like if I can’t talk about the all-consuming issues we’re facing at home, I don’t have anything to say at all.”

According to the NHS, one in seven couples will face difficulties conceiving. Globally, infertility is on the rise, but the perceived stigma around discussing the fertility stage of conception remains.

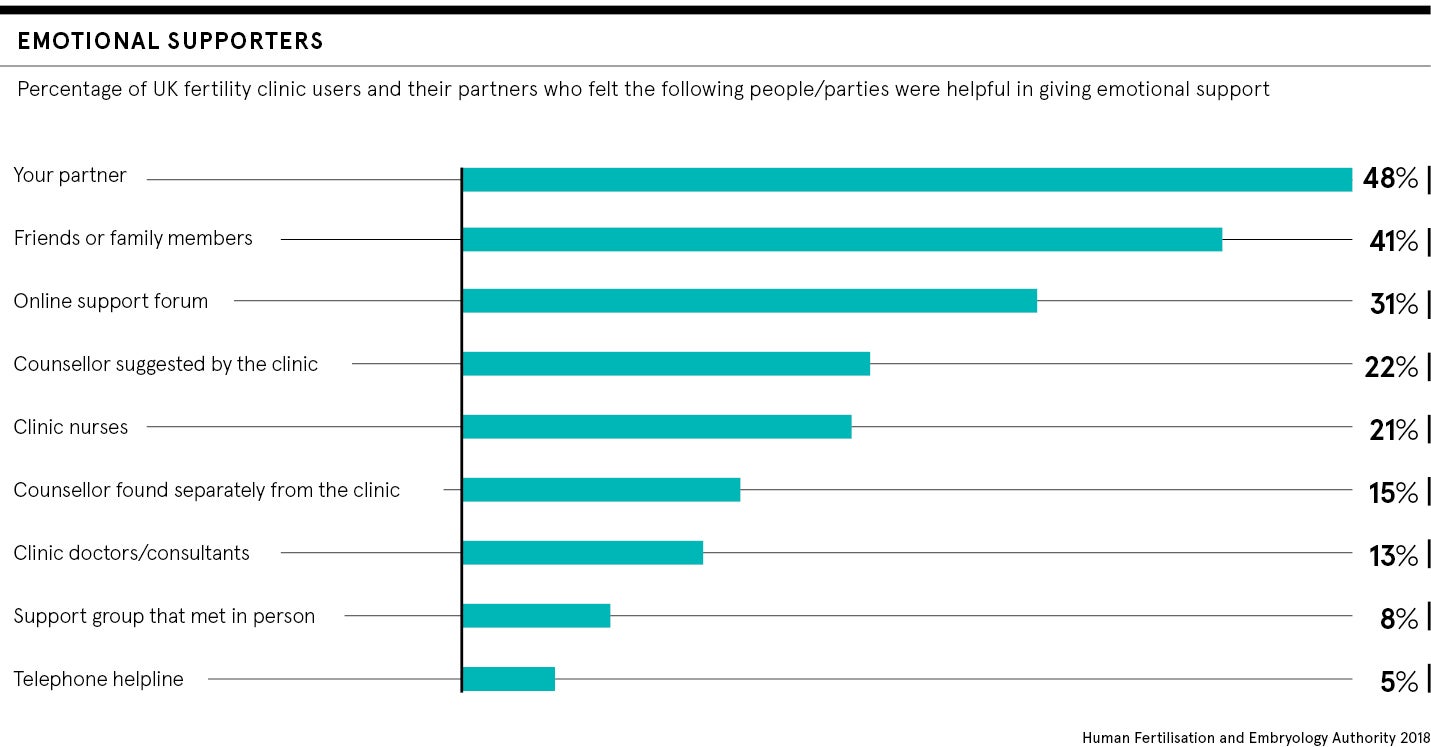

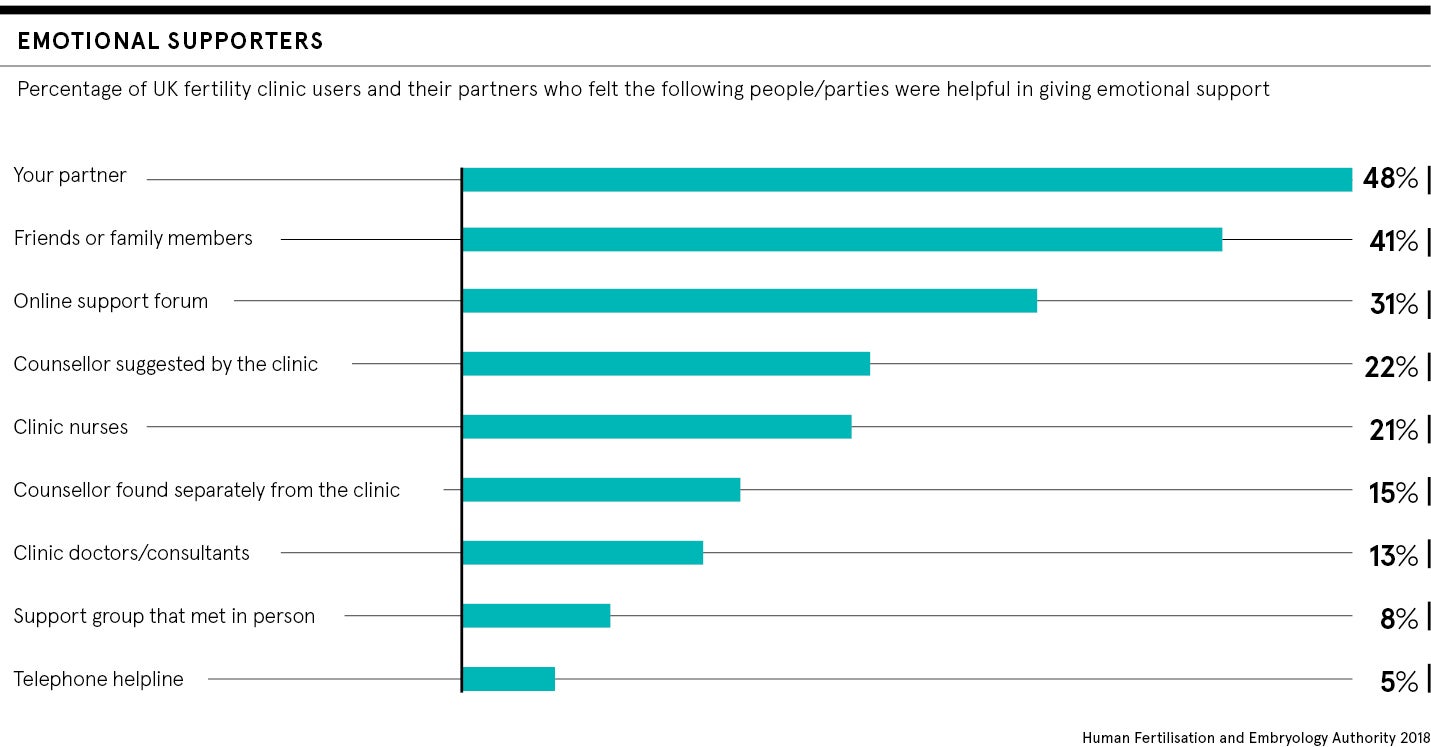

For many, building a fertility community is essential in staving off feelings of isolation. Fertility Network UK runs support groups up and down the UK, offering a safe space where people can come together and discuss the problems they are facing.

Tom has recently joined such a group and is finding the weekly meetings a huge source of support. “Opening up to other people who are having similar struggles has made me feel more normal and made me realise I’m not a failure,” he says.

Fertility support in an online world

Much peer support has moved online. “I was so hungry for other women’s stories that I would spend a lot of time looking at hashtags like #TTC [trying to conceive] on Instagram,” says Emma Forsythe, 33, whose fertility support podcast Big Fat Negative gets 18,000 listeners an episode.

“I felt as if the people around me didn’t understand what I was going through. Every month my period came, it felt like I was grieving for the baby that could have been and it was hugely isolating. I even had thoughts of suicide.”

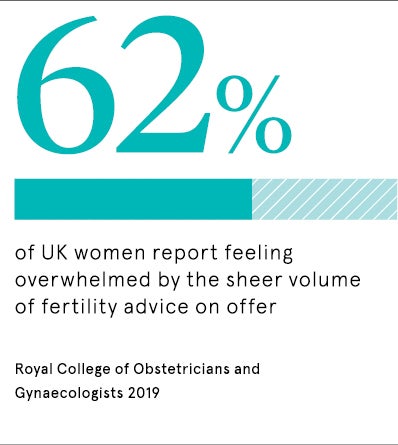

Initially, Emma didn’t use social media to interact with anyone, but found solace in reading about the similar fertility problems other women were facing. She was hyper-aware, however, that Instagram can act as a “highlights reel” of the fertility journey and was also wary of online forums which featured unscientific advice about fertility treatments such as “just eating pineapple”.

Her podcast seeks to counter this with evidence-based discussions of treatments and the lows as well as the highs of the process.

For Hannah Thompson, 32, listening to podcasts was a key source of support during her recent, successful experience of IVF. “I wouldn’t have felt confident enough or had the time to go to a fertility support group,” she says. “I ‘lurked’ on fertility community forums rather than posting, but podcasts felt like the perfect passive community. I listened to a couple of them compulsively and found them incredibly reassuring, as well as a good source of information. I just felt less alone.”

The drawback of the fertility community

Caroline Spencer, psychotherapist and fertility counsellor at the Lister Fertility Clinic, notes that the advent of podcasts and rise of online forums has caused the fertility support landscape to change drastically in the last ten years. It’s now easier than ever to build a supportive fertility community to stave off the loneliness she sees regularly in her patients.

“When people keep choosing to keep quiet, fertility problems can feel like a huge burden to carry,” she says. “Having a community can feel like having travellers on the journey with you, but there comes a time when that community can actually stop being helpful.

“Some people will sadly have a longer route to parenthood and will have to witness many of the people they first made contact with become pregnant. Then the community may no longer be the best support and I would recommend therapy as a way to offload.”

Spencer also recommends drawing on existing support networks wherever possible, by reaching out to friends, family and close colleagues.

Thompson agrees. “I made a conscious decision to talk to people openly and say, ‘This is going to be really tough and I’m going to need support’,” she says. “I told my managers because there was a practical implication in terms of my ability to do my job, but also an emotional one. I was honest with my friends about why I wasn’t drinking and why I needed to be home by 10pm every night [to inject hormones]. I did worry about the stigma attached to speaking about fertility at first, but I had an overwhelmingly positive response.”

Fertility support in an online world

The drawback of the fertility community