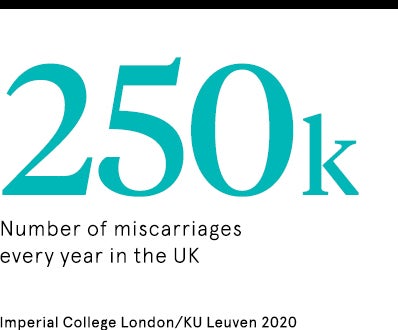

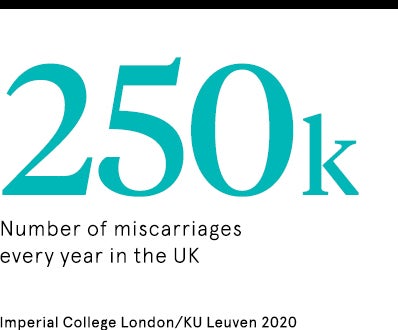

There are an estimated 250,000 miscarriages in the UK every year, but it is not always clear why we find it so difficult to talk about something that happens so often.

Miscarriage can be a lonely and isolating experience, and it is often hard to get answers to questions about possible causes. Doctors generally only undertake investigations after a third pregnancy loss and breaking the taboo of miscarriage is a challenge when people rarely get the support they feel they need.

Artist Foz Foster and his wife Sophie were expecting their third child and had gone for a routine scan when they were told they had lost the baby. “My wife was just lying there and they said there was no heartbeat, that the baby had died and to go home and have a miscarriage,” says Foz.

“We entered the room with expectation and we were leaving it with devastation. It was like being hit in the face with a big hammer. I had no idea what a miscarriage would look like, no one prepares you. It was messy and painful, and the volume of blood was shocking.”

He says the lack of information about what to expect made the experience all the more devastating and the couple went on to have two more miscarriages in the same year. He believes the impact of miscarriage on fathers is often overlooked and he ended up channelling his pain into a 75ft scroll painting honouring the children the couple didn’t have.

There are long-term scars from such a traumatic event, as Dr Jo Mountfield, consultant obstetrician and vice president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, explains: “The taboo nature of the topic, inhibiting discussion, means that the experience of a miscarriage is often not fully processed by women and their families, which may lead to mental health issues.”

Mental health after miscarriage

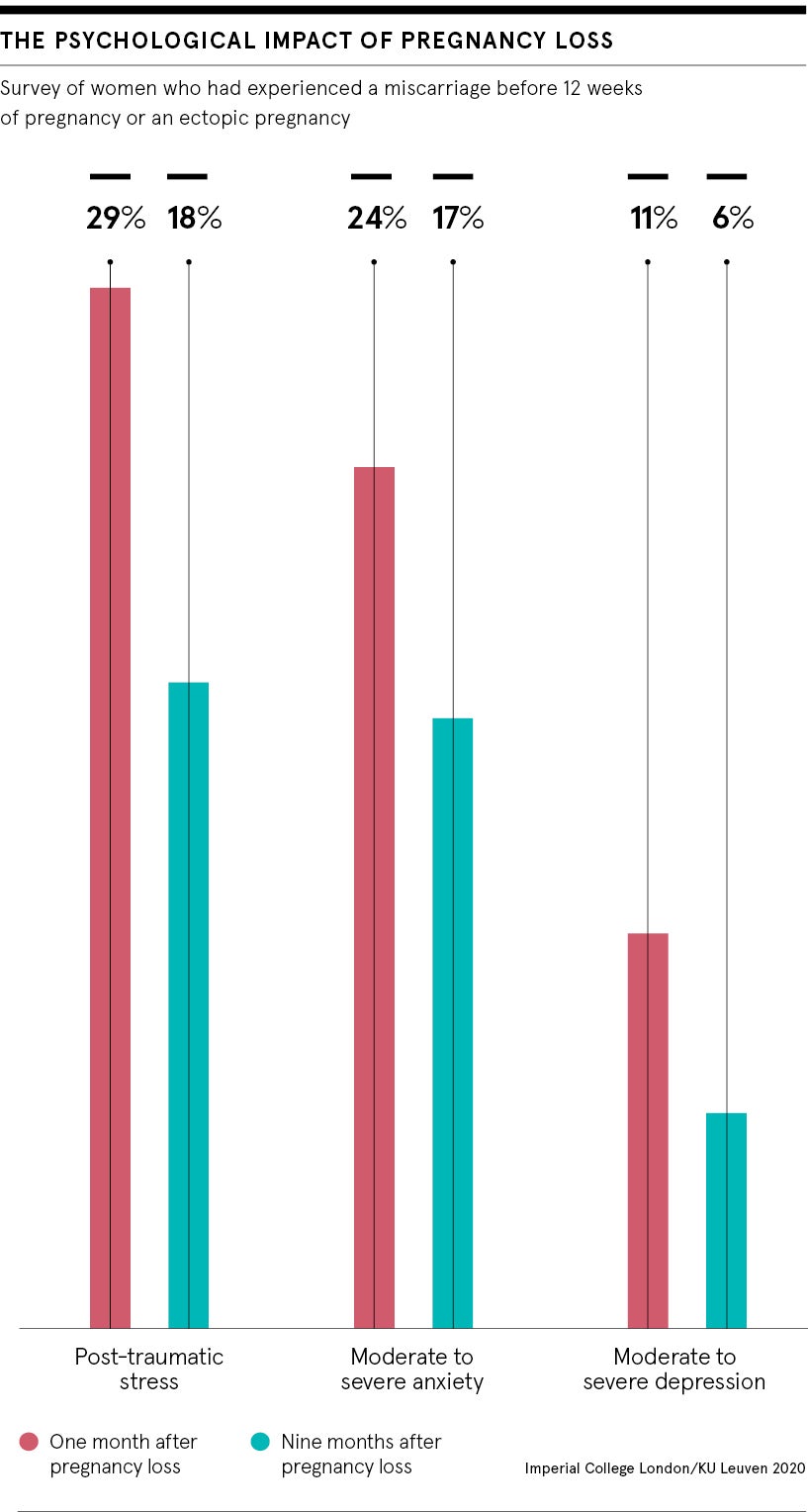

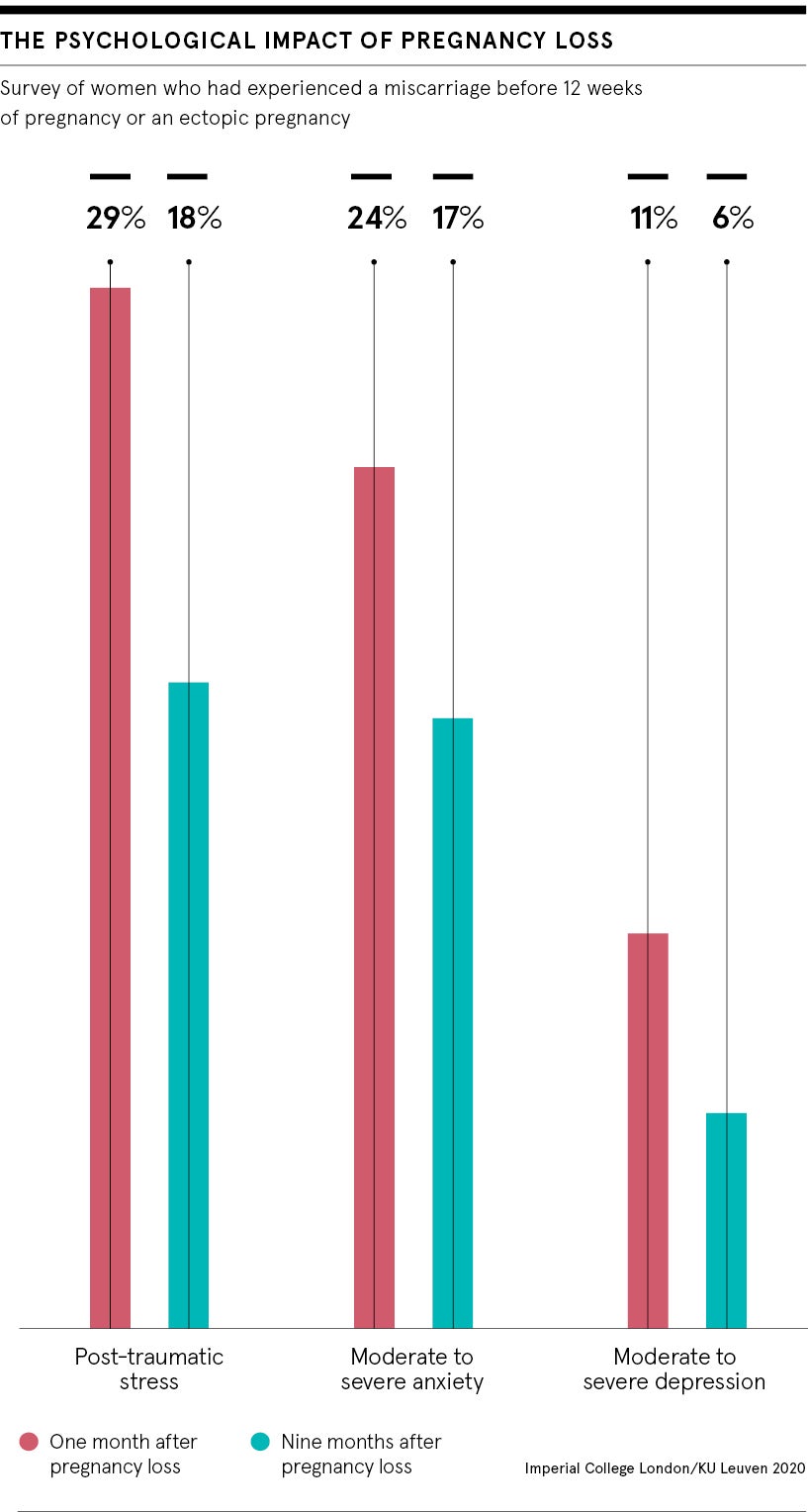

Earlier this year, researchers led by Professor Tom Bourne and Dr Jessica Farren found that early pregnancy loss can have a serious psychological impact, with nearly a third of women who took part in their study experiencing symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following miscarriage.

“We were not surprised by the findings,” says Bourne, “because we know that for many women miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy will be the most traumatic event in their life up to that time. As you might expect, we had observed the level of psychological distress among our patients in clinical practice and wanted to have evidence to quantify this.”

Most miscarriages happen in the first three months of pregnancy, so many people decide not to announce they are expecting until after their 12-week scan, leaving them without support if they miscarry. There is often an assumption that early pregnancy loss is less significant than later miscarriage, but Bourne’s research clearly indicated some women suffer symptoms similar to PTSD following miscarriage, which can affect every aspect of their daily life, including their physical health, relationships, sleep patterns and work.

Julia Bueno has personal experience of recurrent miscarriage, which led her to retrain as a psychotherapist to support others who have lost a baby and to write a book about miscarriage, The Brink of Being. “We usually associate PTSD with veterans coming back from war, but for a woman who has had a miscarriage, it’s such a brutal visceral experience,” she says. “There is no doubt that after my first miscarriage, I ticked the box of PTSD. I had flashbacks for years.”

Anxiety and depression after miscarriage

Breaking the taboo of miscarriage is vital if we are going to improve things for couples who lose a baby. In the early stages, the pregnancy may not yet be visible, but the excitement and anticipation has often begun from the moment of the positive pregnancy test. No matter how early a pregnancy is lost, a dream of the future dies with it.

Walthamstow MP Stella Creasy came out about her two miscarriages when she was expecting her daughter last year. She has been open about the anxiety her previous experiences caused in her pregnancy and feels that breaking the taboo of miscarriage could make all the difference.

“Having a miscarriage can be one of the most devastating experiences any woman has, yet still it’s not widely talked about or acknowledged, which means it can also be one of the most isolating experiences a woman has,” she says. “Just as we wrap so much love around those who are pregnant, so it’s now time to do the same with those who experience pregnancy loss.”

For many women, miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy will be the most traumatic event in their life

Pregnancy after miscarriage is often fraught with fear and this can continue right through to the early days after birth. Healthcare professionals may need training in how to deal sensitively with people who have lost a baby, showing compassion.

Support after a traumatic event

Bueno begged for counselling after her first miscarriage, but when she was finally booked in for a session, the counsellor didn’t turn up. Many of the couples she sees as a therapist have struggled to get the support they need, as not all areas have specialist early pregnancy units and most are offered no formal psychological support or counselling. Pregnancy loss charities are often left to pick up the pieces of a patchy, underfunded service.

Angela Pericleous-Smith, chair of the British Infertility Counselling Association, says when counselling is available, it can be really beneficial to both women and men. “Counselling can help to identify coping strategies and meaningful ways to find a path of acceptance for their experience, which has undoubtedly left them with a sense that their whole world has changed,” she says.

Breaking the taboo of miscarriage may be the first step to improving services, but we also need to appreciate the impact losing a baby has, with so many women experiencing symptoms similar to PTSD. If we are to change the way people are cared for, professional support must be available to everyone who needs it.

Mental health after miscarriage