Every Thursday at 8pm for the first ten weeks of lockdown, the British public put their hands together for frontline workers, celebrating the bravery, resilience and pure determination to turn up to work each day to fight the pandemic. But despite the nation’s outpouring of goodwill, experts have warned of the lasting mental health impact of coronavirus for doctors, nurses and care workers, some of whom will have experienced the most distressing incidents of their working lives.

Studies from the SARS and MERS outbreaks suggest epidemics increase the risk of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in healthcare professionals.

Justin Walford, an A&E nurse at Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, says that while his team is very resilient, the last few months have been challenging, with many nurses experiencing panic attacks. “One time, I had a bit of a cough in the middle of the night,” he says. “You tell yourself you’re probably not going to die in two weeks, but those feelings can be very difficult.”

The most haunting aspect of the pandemic has been preventing patients’ loved ones visiting them in hospital, he says. “It goes against everything people working in medicine stand for. You don’t want people to die alone,” says Walford.

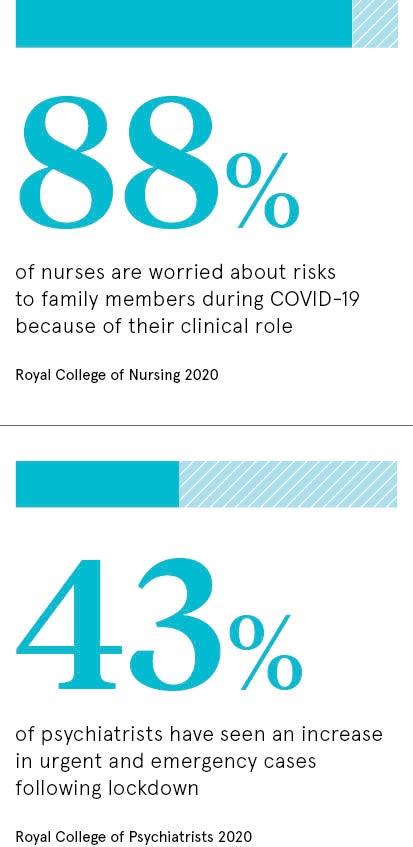

Frontline workers worried for family members

Potentially passing the virus on at home has been another source of significant stress for frontline workers. Nine in ten nurses surveyed by the Royal College of Nursing said they worried about risks to family members during COVID-19 because of their clinical role. Respondents reported ongoing depression, anxiety, stress and emerging signs of PTSD.

Respiratory nurse Brooke McCutcheon from Bristol Royal Infirmary says her hospital leapt into action at the start of the pandemic, creating new COVID wards and redeploying staff, but the initial uncertainty was terrifying. “I remember the matron coming in and saying we had to prepare for the whole hospital to be on ventilators and pointing out that some of us might get really sick,” she says. “Frontline workers felt like cannon fodder at that point.”

During the lockdown, things were made even more difficult by not being able to socialise on days off. “It felt like all you were doing was working, dealing with horrible situations and then having no outlet. It was isolating,” says McCutcheon.

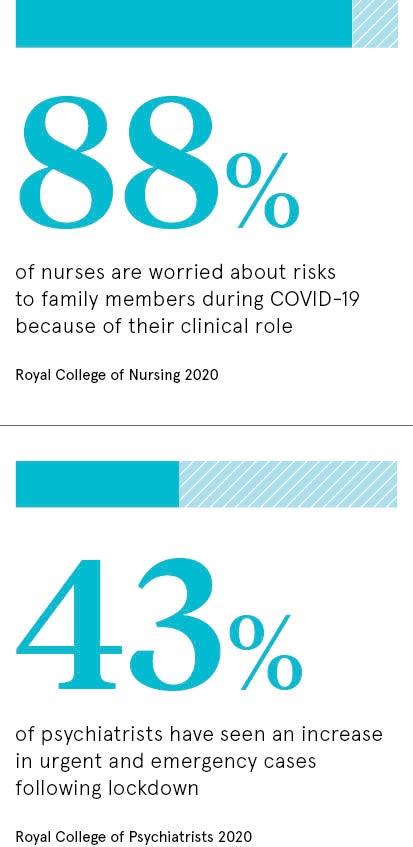

It’s too soon to know the long-term mental health impact of coronavirus on frontline workers and whether rates of PTSD will increase. Research from the Royal College of Psychiatrists has pointed to a “tsunami” of mental illness still to come in the general population. Some 43 per cent of psychiatrists have seen an increase in urgent and emergency cases following the COVID-19 lockdown.

Consequences of processing a traumatic event

A phenomenon of particular concern for healthcare workers is “moral injury”, a term that originated in the military. It occurs when psychological distress results from actions which violate someone’s sense of right and wrong. Those who develop moral injury are likely to experience negative thoughts about themselves and it can lead to PTSD.

“Staff have been asked to make tough decisions where there’s no right answer,” says psychologist Alan Barrett from Manchester. “Deciding who’s going to get the ventilator because you haven’t got enough of them; that weighs heavy on people.”

When the coronavirus crisis hit, many hospitals adopted measures to protect staff mental health. The Royal Marsden Cancer Charity emergency appeal raised £1.6 million, some of which will fund psychological support for staff. And at Barts Health in London, the chaplaincy introduced a 24/7 helpline for frontline workers.

But psychologist Joanne Lusher from the University of West Scotland believes the mental health impact of coronavirus and the level of support that could be required in years to come must not be underestimated. “The psychological burden that is going to follow the response to COVID-19 is going to be immense,” she warns.

There’s also the question of salary. Nurses, care workers and junior doctors have been excluded in the government’s recently announced pay rises for public sector employees. Walford describes a pay freeze as a “kick in the teeth” for staff “who stepped up to the plate during the pandemic”.

The weekly clap for carers might have stopped, but the crisis isn’t over yet. Psychologist Barrett points out that healthcare workers are already anxious about a possible resurgence in cases. “They’re not sure whether they’ve got a second wave in them,” he says. “The first one was so exhausting, frightening and stressful.”

Frontline workers worried for family members