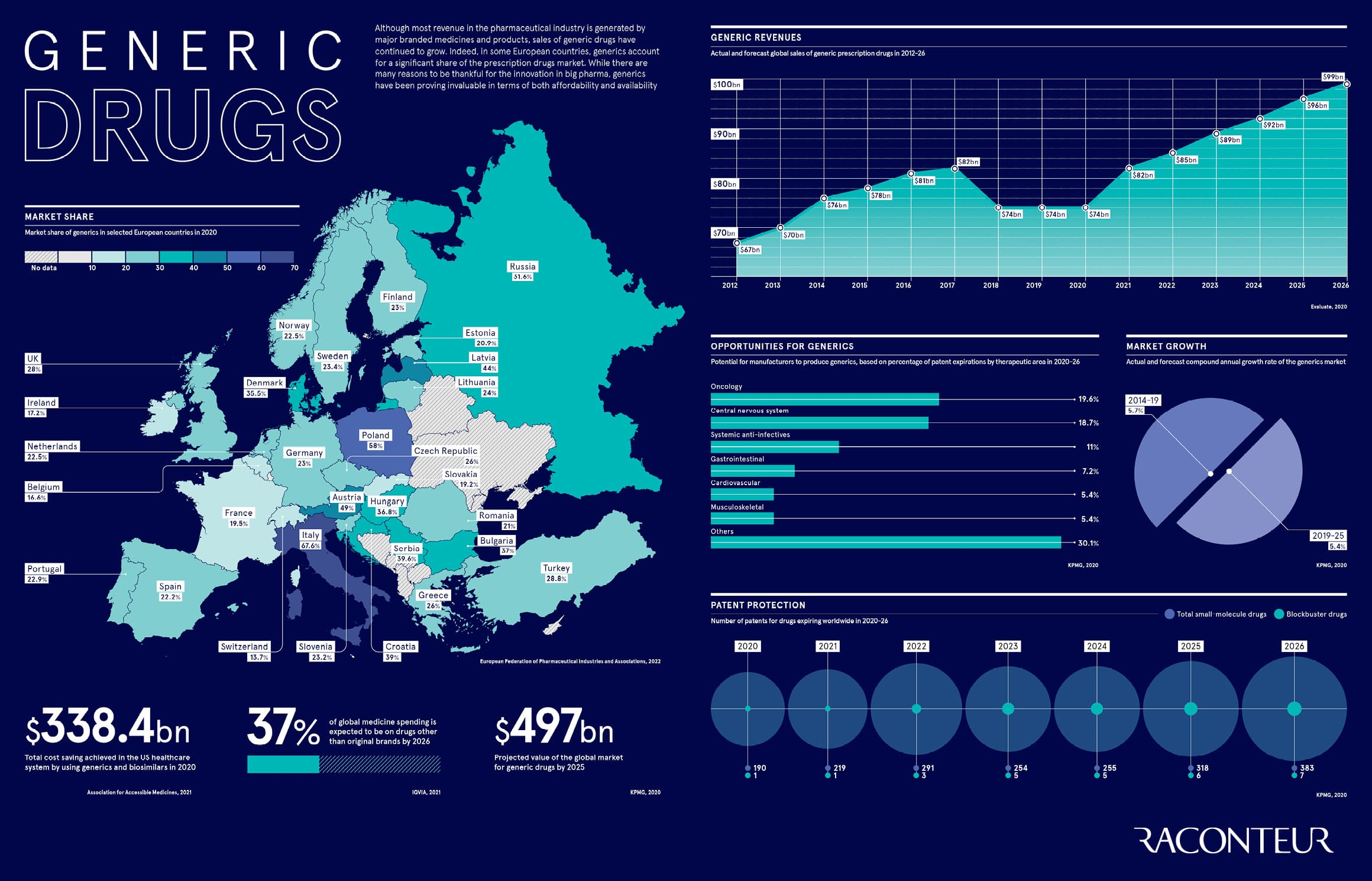

Although most revenue in the pharmaceutical industry is generated by major branded medicines and products, sales of generic drugs have continued to grow. Indeed, in some European countries, generics account for a significant share of the prescription drugs market. While there are many reasons to be thankful for the innovation in big pharma, generics have been proving invaluable in terms of both affordability and availability

Published in