It matters where you live when cancer comes knocking. There are around 20,000 extra cancer cases in more deprived areas of Britain every year, according to Cancer Research UK. That’s almost 60 additional diagnoses a day and an “unacceptable reality in 2020”, the charity says.

The 20,000 figure may be sobering, but for many health experts, it’s not surprising. We’ve known for decades that significant health inequalities exist in the UK. And it’s not just cancer that’s affected; life expectancy also strongly correlates with wealth.

In 2010, a University College London (UCL) Institute of Health Equity report, led by epidemiologist Professor Sir Michael Marmot, found people living in the poorest neighbourhoods in England will die seven years earlier on average than people in the richest parts of the country. The reasons are multi-faceted, from poor access to healthcare services and housing to more dangerous jobs and food insecurity.

It’s stark and it’s not fair, but it’s also changeable

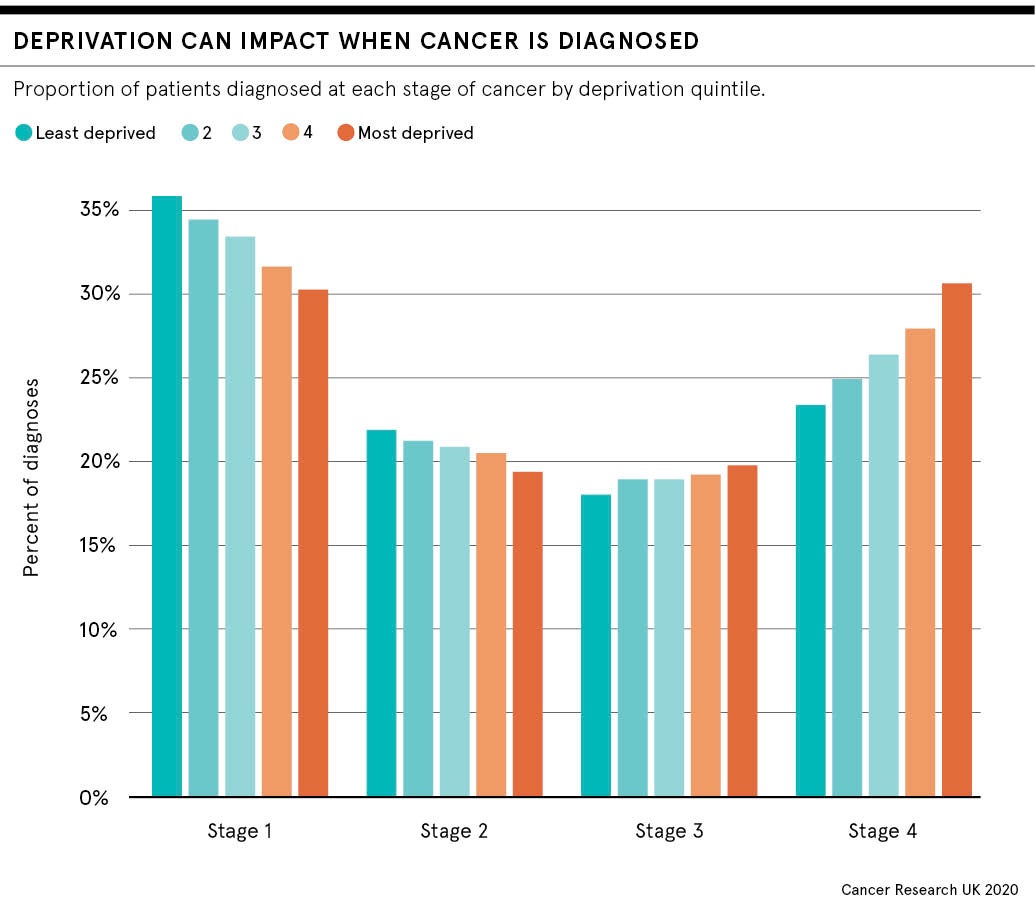

People in poorer areas are not only more likely to get cancer, they’re also more likely to die from it, says Cancer Research UK. Compared to the richest regions, people in the most deprived areas are 50 per cent more likely to have their cancer diagnosed through emergency routes, when the disease is often at a late stage and therefore harder to treat. At every step of the cancer care pathway, poorer people are at a disadvantage.

“It’s stark and it’s not fair, but it’s also changeable,” says the charity’s science information officer Dr Rachel Orritt.

Cancers associated with socio-economic deprivation

Researchers have found the most evident socio-economic differences are in cancers linked to smoking, such as lung and throat cancer. Rates of smoking-related cancers are three times higher for the poorest populations compared to the richest.

But it’s hard to stub out the habit without sufficient support. Cancer Research UK believes protected funding, raised through a levy on the tobacco industry, to pay for more support programmes that combine expert behavioural support with quit-smoking aids, such as tablets or nicotine-replacement therapy, could help.

Research in January from Cancer Research UK and Action on Smoking and Health found that almost a third of local authorities have axed their specialist stop smoking services in the last five years.

Obesity is another issue and the second-largest preventable cancer risk factor after smoking, accounting for around 23,000 cases in the UK each year. Children from the poorest areas are twice as likely to be obese compared to those in the least deprived. And obese children are around five times more likely to be obese in adulthood when the risk of cancer increases.

Cancer Research UK wants more public health efforts to reduce obesity and is calling on the government to implement measures outlined in its July obesity strategy, which include restricting advertising and price promotion offers on junk food.

Whether these proposals go far enough remains to be seen. “I think a lot of what we do sometimes feels as though we’re just tinkering around the edges,” says Dr Sara Macdonald, sociologist in primary care at the University of Glasgow. She worries that policies urging people to make better lifestyle choices may not take into account the underlying reasons behind unhealthy behaviours.

“These kinds of things may just not be top priorities if your life is more challenging,” says Macdonald. “The circumstances for people living in areas of deprivation are not always conducive to stopping the behaviours we are encouraging people to stop. Life is harder and we should probably acknowledge that.”

Reducing health inequalities is far from simple

What makes tackling health inequalities so challenging is that every new policy requires patience, says Professor Georgios Lyratzopoulos, cancer epidemiologist at UCL. As factors that lead to the development of cancer take many years to show up, it could be decades before efforts to reduce the risk look as if they’ve worked. “This isn’t like preventing people from being injured in a car accident, where if we started with no seatbelts, but introduced them tomorrow, the prevention would happen straightaway,” he says.

But targeted efforts relying on the expertise of local services that understand the unique challenges of their residents could be important. Plus, in cancer care, we need to understand better the barriers to seeking help at an earlier stage; why someone might skip their screening appointment or put off going to the doctor if they’re experiencing symptoms such as a cough that lasts for longer than three weeks, which might suggest lung cancer.

“If you live in a more deprived community and the outcomes are poorer, then your attitude towards cancer may be more fatalistic,” says Macdonald. “Whereas if you live in a more affluent community, you will probably know people who have survived cancer. All these things come into play and affect how we think about our health.”

The Marmot review suggested health inequalities are largely preventable, but a successful strategy must take into account all the social determinants of health, such as education, jobs, housing and community. This is hard to achieve without sufficient funding for support services and local government. Ten years on from the original report, the authors say the health gap has grown between wealthy and deprived areas. They note: “If health has stopped improving, it is a sign that society has stopped improving.”

As the country continues to endure the challenges of the coronavirus pandemic, there are many question marks over how the NHS can adapt and recover from months of disruption. Cancer care in particular has been heavily impacted by the crisis. But COVID-19 could also be a catalyst for change, says Macdonald. “If there’s been one benefit of COVID, it has been that people have started to acknowledge the health inequalities in our society. We need to take this seriously.”

It matters where you live when cancer comes knocking. There are around 20,000 extra cancer cases in more deprived areas of Britain every year, according to Cancer Research UK. That’s almost 60 additional diagnoses a day and an “unacceptable reality in 2020”, the charity says.

The 20,000 figure may be sobering, but for many health experts, it’s not surprising. We’ve known for decades that significant health inequalities exist in the UK. And it’s not just cancer that’s affected; life expectancy also strongly correlates with wealth.