It was a remarkable year of firsts. Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space, meanwhile President Kennedy announced America’s intention to land a man on the moon. But in the UK, it was the extraordinary achievements of Aubrey Leatham and Geoffrey Davies that stole headlines in 1961. Leatham, a leading cardiologist, and Davies, his chief technician, made history by implanting the UK’s first internal pacemaker at St George’s Hospital in London.

When you consider that the average human heart beats 40 million times a year, it’s perfectly logical to think that nature may provide the best power source

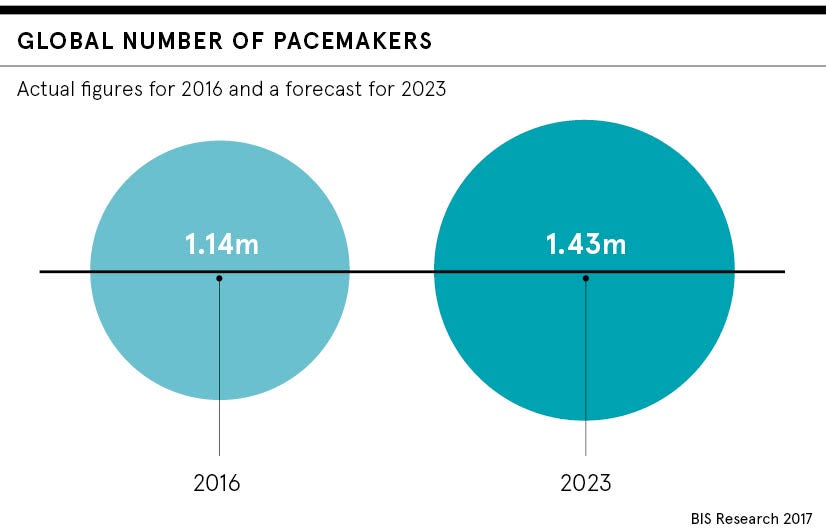

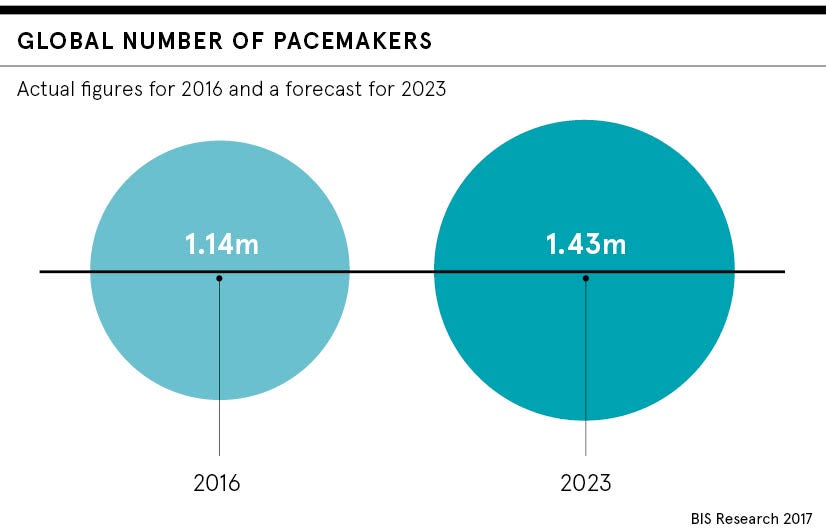

Fast forward to the present day and some 36,000 patients receive a first pacemaker in the UK each year. Perhaps what is most remarkable is that more than 50 years on, technological advancements in standard pacemakers have essentially been only incremental.

However, groundbreaking work by two Shanghai-based researchers represents a dramatic sea-change in thinking. Zhang Hao and Yang Bin claim to have found a way to power a pacemaker, not with a standard lithium battery, but by using the heart muscle activity itself to power up the system.

What are the benefits of a heart-powered pacemaker?

While this technological advancement is in its early stages – it has been tested in a pig, but not in humans – Dr Andrew Grace, one of the UK’s leading cardiologists, thinks that if the research is validated, it could be regarded as “an exceptionally useful development”.

Dr Grace, who works primarily at the Royal Papworth Hospital in Cambridge and has fitted around 3,500 pacemaker devices in a 31-year career, says the idea of heart-powered pacemakers is not new.

“It been talked about for many years. When you consider that the average human heart beats 40 million times a year, it’s perfectly logical to think that nature may provide the best power source,” he says.

Providing the technology proves useful in clinical trials and is then approved for commercial use, it could bring about two major multi-directional benefits for both patients and implanting cardiologists.

Dr Grace explains: “On average, a pacemaker battery lasts between seven-and-a-half and ten years. In terms of my workload, I spend a quarter of the time that I devote to pacemakers, fitting replacements. If cardiologists didn’t have to do this, they are likely to redirect resources to helping patients in other ways.”

When will the new pacemakers hit the market?

He also thinks this development could help combat infection risks by reducing the need for device replacement, which could have particular advantages for younger patients who require a pacemaker.

“Traditionally, we’ve been really cautious in recommending pacemaker implantation in younger patients. On occasions, this delays procedures. That’s because every time we replace a pacemaker, there’s a risk of infection. Therefore, a teenager currently receiving a device might require maybe five or six replacements in their lifetime, all of which will add marginal risk,” he says.

“But if we could use the heart as a natural power source, we could install pacemakers earlier without having to be overly concerned about the potential risks attached to generator replacement.”

So how long does he think it will take for the multinational pacemaker manufacturers, such as Medtronic, Abbott and Boston Scientific, to commercialise such piezoelectric systems?

“I can’t speak for industry, and with research still at a relatively early stage, it is difficult to give an accurate timeline. But I’d strongly anticipate within the next decade we will see advances in energy generation, storage and delivery to the extent that it might be possible to tell a patient the next device they have fitted will be the last one they’ll need,” says Dr Grace.

But Dr Francis Murgatroyd, consultant cardiologist at King’s College Hospital, London, doesn’t entirely agree. “Battery-less devices won’t necessarily eliminate operations in the future,” he says. “If I had a 15-year old pacemaker it would not have a number of features that have recently become standard, such as the ability to be checked over the internet or undergo MRI scanning safely. But it’s certainly true to say there would be much fewer operations.”

Are leadless pacemakers the future?

Dr Grace feels that leadless pacemakers, not to mention a host of other developments including wireless generators and biological pacemakers, aren’t necessarily an improvement on conventional approaches for the majority which, he says, already provide excellent benefits to more than 7,000 patients at his own hospital. Nor does he believe these other developments will represent a paradigm shift for heart-pacing technology.

It is a view shared by Dr Murgatroyd, who says: “With 60 years’ experience, we’ve learnt to build conventional pacemakers with fantastic reliability. If we wanted to, we could easily double their battery lives just by making them a little bigger.”

That’s not to say that he is not excited about the latest technological developments. However, he advises a cautionary approach, especially given that one of two leadless pacemakers that recently came to market had to be withdrawn “due to implant-related complications and issues with battery reliability”.

“Leadless pacemakers are a remarkable development in miniaturisation and may well be the future,” says Dr Murgatroyd. “However, the models available in the next year or two will be fairly basic. There is some way to go before they can replace the advanced functions available in conventional devices. Even more importantly, it will be many years before we know about their long-term reliability, especially as they will be virtually impossible to remove once bedded in.”

When will the new pacemakers hit the market?