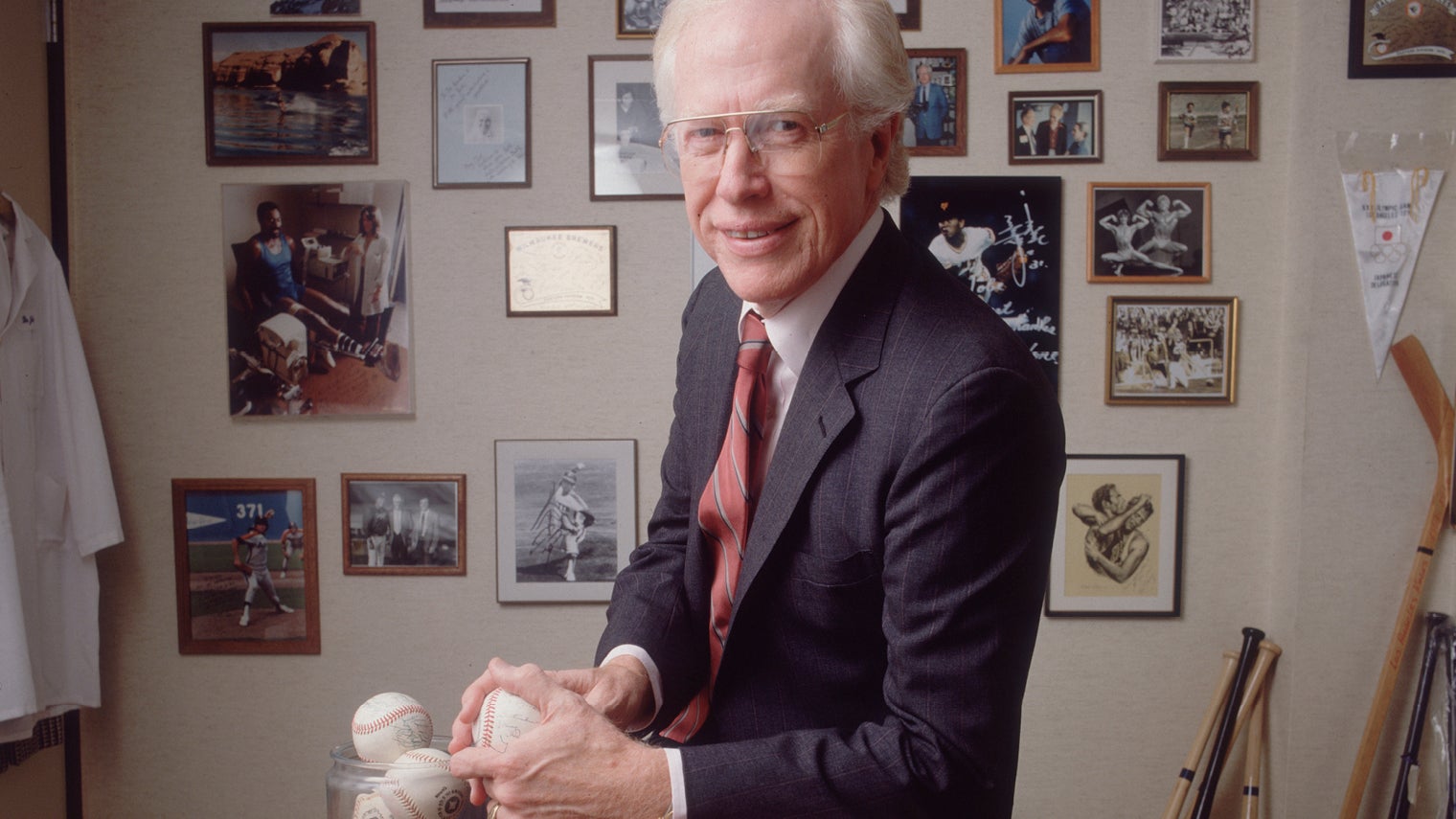

In baseball circles, Frank Jobe is a legend despite never playing in the professional ranks. Honoured in baseball’s Hall of Fame in 2013, Dr Jobe’s contribution is as extraordinary as it is remarkable.

Just ask Tommy John, a pitcher for the LA Dodgers. In July, 1974, John tore a ligament in his arm so badly that doctors told him his career was over. John, who was in his prime, persuaded team doctors to find a solution that would prolong his career.

Enter Dr Jobe, orthopaedic surgeon and keen baseball fan. By taking a six-inch tendon from Tommy John’s good arm and attaching it to the injured one, he not only fixed the pitcher’s throwing arm, but in doing so he extended his career by 14 years.

Some 45 years later, hundreds of Major League Baseball players have undergone the same revolutionary ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) surgery, or Tommy John surgery (TJS) as it is more commonly known.

But the transplant procedure is not just reserved for athletes. Every year thousands of patients take advantage of it too. Some are amateur sportsmen and women, but the majority of beneficiaries who undergo UCL surgery have never even picked up a baseball.

The question is, if it hadn’t been for Dr Jobe and the sport of baseball, would UCL surgery exist and would ordinary people be able to benefit?

Jeffrey Dugas, orthopaedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist who has carried out more than 2,000 UCL operations, says: “We owe a lot to Frank Jobe. He was a true pioneer and one of the fathers of modern sports medicine. But the field we work in, which is relatively young and therefore not weighed down by the shackles of traditional medicine, must take enormous credit too. It encourages innovation and the techniques that we use often find their way into general surgeries.”

Based in Birmingham, Alabama, Dr Dugas has left his own mark. He noticed how many patients with partial tears of the UCL were having TJS when it wasn’t necessary. By using collagen-coated fibre tape, which acts as an internal brace, however, he and his team discovered they could repair partial tears without the need for full reconstructive surgery.

“We adapted the surgical technique from a foot and ankle specialist, who had created the brace for patients after ankle surgery. Essentially, anyone who undergoes the surgery can have a stable elbow in two to three months and make a full recovery in six months rather than a year. The technique is transferable too to non-sporting patient populations,” he says.

Dr Dugas says that while 95 per cent of his patients are baseball pitchers, a growing number of patients, who have no connection to sport whatsoever, but are suffering from long-term elbow instability, are “interested in this less-invasive form of elbow surgery”. In one recent week, he says his office fielded 25 calls about the UCL repair with internal brace procedure.

Across the Atlantic, in Sheffield, Derek Bickerstaff, consultant orthopaedic surgeon and one of the UK’s leading knee surgeons, believes it is sports medicine’s collaborative and holistic approach to treating patients that is the key to faster recovery times.

Dr Bickerstaff, who also consults for One Health Group, explains: “When performing anterior cruciate ligament surgery, we make tiny keyhole incisions which is designed to cause minimal disruption to the tissue and the knee capsule. It also means that we can begin rehabilitation almost straightaway.

“In this respect, I work as part of a multi-disciplinary team which includes highly skilled and experienced physios. We do everything together. They are often present in the initial consultancy and will even work with the patient prior to the operation in what we call ‘prehabilitation’.”

Practising since 1993, Dr Bickerstaff says this multi-disciplinary approach is the reason his patients, whether they’re pub footballers or professional athletes, can make a full recovery in seven to nine months rather than two to three years.

But there is a growing school of thought in the orthopaedic community that surgery is not always the answer. Take research conducted in 2013 by the Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Society, for example, which compared the outcomes of the two groups of patients, aged between 35 and 65 years old, who were suffering from a degenerative medial meniscus tear in the knee.

Patients were divided into two groups. Some were given keyhole surgery to fix the meniscal tear, while the other group received sham surgery. In other words, they were given a general anaesthetic, their knee cut open, but no arthroscopy surgery performed. Most crucially, the patients in both groups were “blind” to which form of treatment they received.

Curiously, the results revealed that for patients with a medial meniscal tear, the outcomes after keyhole surgery were no better than for those who underwent sham surgeries.

Roger Wolman, NHS consultant in rheumatology and sports exercise medicine, says: “These double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trials show that keyhole knee surgery carried out on elite athletes in their 20s is not always transferable to older patients.

“Of parallel concern, there has been a ten-fold increase in keyhole surgery of the hip. Worryingly, some surgeons are replicating this surgery for elderly patient populations after seeing positive results in younger people, many of whom come from a sports background. I suspect that in the next five or ten years we are going to see papers which provide evidence that this surgical procedure does not work for older patients.”

Dr Wolman adds that while surgery “is sometimes totally necessary” in many cases “extensive physiotherapy, postural or gait re-education” is sufficient to ensure a successful outcome for many patients.

Whatever the remedy, be it surgery, rehabilitation or both, many innovative techniques first developed in the field of sports science are shaping the future of general medicine.