Indie-Rose Clarry once suffered up to 200 seizures a day. The 5-year-old girl from Clare, Suffolk has Dravet syndrome, a rare and chronic form of epilepsy that affects around one in 15,000 children.

None of the ten pharmaceuticals the young sufferer tried were effective, but medical cannabis has given her a new lease of life and the ability to attend school. “Before, I don’t think she was properly aware of life,” says her mother Tannine Montgomery. “But since she’s started taking cannabis oil, Indie-Rose has become her real self.”

The UK legalised the use of unlicensed medical cannabis two years ago, provided it is prescribed by a doctor listed on the General Medical Council’s specialist register, not GPs.

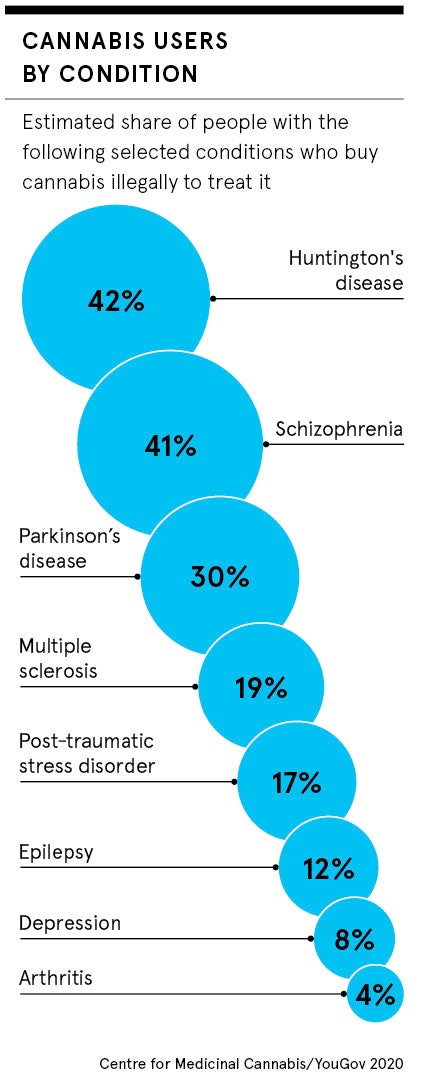

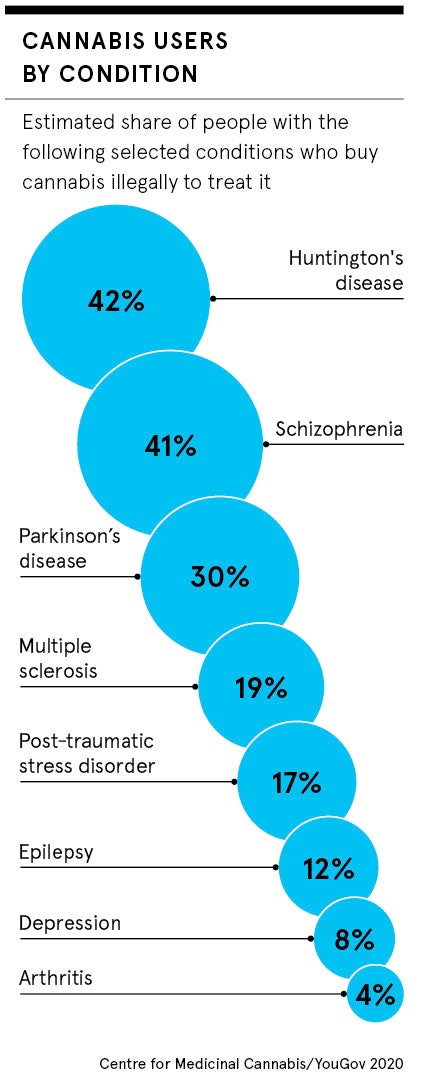

Yet Montgomery, like many of the estimated 1.4 million people forced to use other means, according to a survey by the Centre for Medicinal Cannabis, and Cannabis Patient Advocacy and Support Services, is struggling to obtain the necessary drugs. She says private healthcare, the only option because NHS doctors refuse to prescribe them, costs more than £4,000 a month.

Instead, the family has been forced to travel to the Netherlands where they can buy the drugs for a third of the price. But last July, her daughter’s cannabis oils were confiscated at London Stansted Airport because, unless prescribed, possession or supply of cannabis remains illegal. “We’ve been pushed from pillar to post,” adds Montgomery.

Tight requirements outside clinical trials

Department of Health figures published last September revealed that in the first eight months after medical cannabis was legalised, there were just 12 NHS prescriptions issued for unlicensed cannabis medicines.

However, there were more than 1,000 prescriptions for the two licensed cannabis-based drugs, Sativex and Nabilone, which are given to patients undergoing chemotherapy and have been subject to expensive and lengthy randomised control trials.

According to Steve Moore, founder of the Centre for Medicinal Cannabis, an industry lobby group, this is because the UK, unlike the Netherlands, lacks a dedicated medicinal cannabis regulatory system and so patients can only access it under a system designed for traditional medicines.

“Realistically, because of time and cost, licences won’t be obtained for most cannabis-based medicines,” says Moore. “Although we’re not expecting a revolution in the healthcare system, given the scale of informal use, it’s important there is an attempt to improve access and prescribe more.”

Unclear evidence for cannabis-based treatments

Unlicensed cannabis products are only available on the NHS under what are known as “specials” and after other treatments have been tested. Only specialists, who could be deemed culpable should there be an adverse reaction, can prescribe them and many remain unconvinced by the current evidence.

Dearth of research led to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, or NICE, publishing guidance last August recommending that medical cannabis should not be prescribed until more research is done into the “long-term safety and effectiveness”.

The government’s position is similar, with the doubts over the cost, safety and efficacy. “We continue to work hard with the health system, industry and researchers to improve the evidence base for other cannabis-based medicines,” according to the Department of Health and Social Care.

This is set to change, however, with a group of scientists led by specialist, Professor David Nutt currently conducting Europe’s largest study into the effects of medical cannabis. About 20,000 patients will be treated for a range of disorders including epilepsy, chronic pain and multiple sclerosis.

Complicated logistics of medical cannabis industry

But even for the tiny minority fortunate enough to get a prescription, there are a number of logistical loopholes to navigate. Firms wanting to import products into the UK must apply to the Home Office and be checked by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Although prescriptions are often only valid for 28 days, this process can take up ten weeks and therefore expire before the drug can be sourced.

The first shipment of medical cannabis, which was imported from the Netherlands, did not arrive until February 2019, four months after it was legalised.

The first shipment of medical cannabis, which was imported from the Netherlands, did not arrive until February 2019, four months after it was legalised.

“The costs are absolutely inordinate and the timeframe huge,” says Baroness Molly Meacher, chair of the all-party parliamentary group for drug policy reform. “There must be more flexibility.”

But there are signs of improvement. While prescriptions can only be made on a case-by-case basis and medical cannabis cannot be stored in the UK, vastly limiting the supply, according to Baroness Meacher, a system of “mini bulk” imports is being explored to allow the import of multiple prescriptions at once.

The private sector is already running at a much faster rate and provides a vision of what could be. “A year ago in the UK, it was pretty much like a desert,” says Jonathan Nadler, managing director at Lyphe Group, which runs seven private clinics in the UK. “But that’s completely transformed.”

Nadler says that it now takes less than two weeks to pass the relevant checks and supply medical cannabis to the 1,000 patients on the company’s books. “If they allow manufacturers to store cannabis, it will become an even more affordable market,” he adds.

But for patients like Indie-Rose, the expense of obtaining medical cannabis outside the NHS has already pushed her family’s finances to the limit.

“We managed to raise £32,000 from friends and family, but that’s a lot of money,” her mother says. “We can’t keep it up forever and if my daughter doesn’t take this medication, she will go back to hospital. All we are asking for is a prescription to be filled by an NHS doctor.”

Tight requirements outside clinical trials

Unclear evidence for cannabis-based treatments

Complicated logistics of medical cannabis industry