Bacteria are better than any of us at adaptation. Reproducing in minutes, evolution can happen rapidly. This is how antimicrobial resistance occurs: the germ that develops armour to medication is able to pass this trait to its offspring.

It’s survival of the fittest. Humans are constantly playing catch-up and need new antibiotics for when the older drugs no longer work. But we’re simply not developing them fast enough.

A lot of people think at the first signs of feeling slightly ill, go to the doctor and get an antibiotic. We need to stop treating these things like sweets

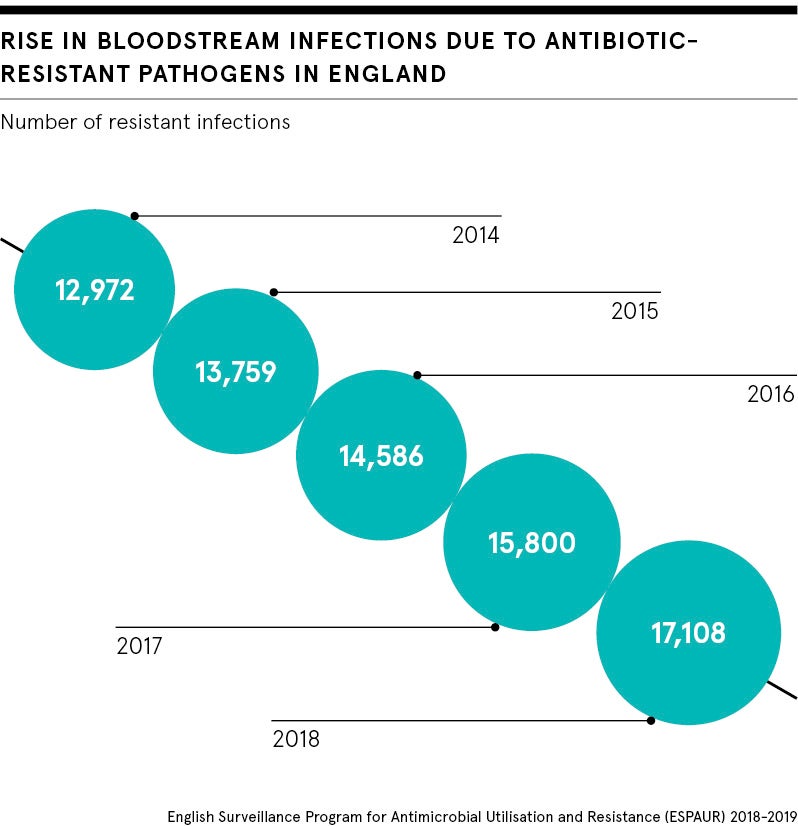

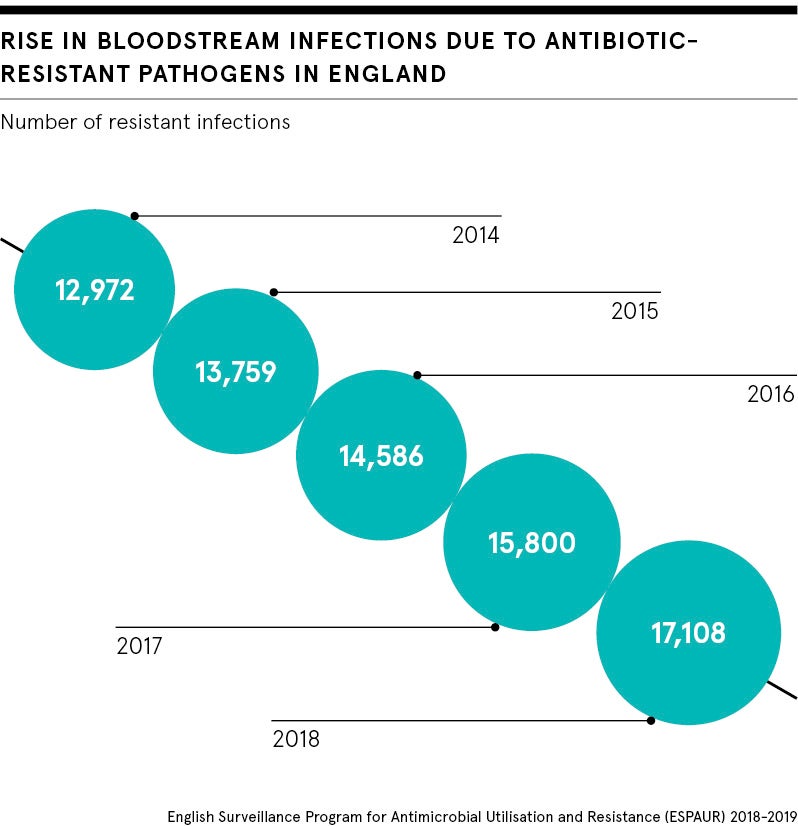

Antimicrobial resistance is a huge and ever-growing problem. Resistant bacteria already cause more than 700,000 deaths globally every year. Former UK chief medical officer Professor Dame Sally Davies recently called for an Extinction Rebellion-style campaign to help people and politicians see that antimicrobial resistance is as much of a crisis as climate change.

Economist Lord Jim O’Neill agrees that public awareness of this issue is dangerously low. From 2014 to 2016, he led an international assessment, the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), to analyse the global problem of rising drug resistance and propose concrete actions for tackling it.

“Antimicrobial resistance doesn’t have its Greta Thunberg. But the consequences of not solving the problem are more known than climate change,” he says. “It’s a major dilemma. A lot of people think at the first signs of feeling slightly ill, go to the doctor and get an antibiotic. We need to stop treating these things like sweets.”

Greater awareness from the public could help as overuse of these medicines has led to the problem in the first place. But until pharmaceutical companies invest in new antimicrobials, the threat of a post-antibiotic era, when a simple ear infection could be fatal, will not go away.

Significantly, in July 2019, the Department of Health and Social Care announced that the NHS will test the world’s first subscription-style payment model to incentivise pharmaceutical organisations to develop new drugs for resistant infections.

Why aren’t new antibiotics being developed?

The trial will be led by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), NHS England and NHS Improvement. Pharma companies will be paid upfront for access to medication based on its usefulness, rather than the amount that will be prescribed.

We’re used to paying for an antivirus subscription to protect our technology, so could an antibacterial equivalent be what’s needed to safeguard public health?

Dr Anna Maria Geretti, professor of virology and infectious diseases at the University of Liverpool’s Institute of Infection and Global Health, points out that something needs to change. The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance has outpaced innovation.

“Resistance to antibiotics is a growing threat globally. There is increasing mortality, especially with certain types of infections for which there are very limited treatment options, such as gram-negative bacteria, that are recognised by the World Health Organization as ‘priority pathogens’ and a global threat,” she says.

But for a pharmaceutical company, research and development costs for a new antibiotic are far and above the revenue generated once the drug reaches the market. As the medicine will target a high-risk infection, its use would have to be restricted so pathogens do not become resistant to it too.

“Appropriate usage, although an important healthcare objective, is in conflict with pharmaceutical companies’ revenue objectives,” says Beth Woods, senior research fellow at the Centre for Health Economics.

Launching a brand-new payment model

That’s where this new payment model comes in. It’s based on “delinkage”, where a drug’s profitability is isolated from its volume of sales. The scheme proposes that pharmaceutical companies will be paid upfront for access to new antibiotics based on how useful they are expected to be for patients and the NHS, rather than how often they will be used.

Ms Woods is part of the team at the Policy Research Unit in Economic Evaluation of Health and Care Interventions, which provides cost-effectiveness analysis to the Department of Health and Social Care. Her group will come up with a value-based payment for the new antibiotics submitted for the trial.

The first phase of the project will focus on developing an outline for the payment model and selecting two antibiotics to undergo the assessment, which is likely to conclude at the end of 2020.

“We will learn through this trial how effective it is in bringing innovation to patients in need. In the forthcoming months, we expect to see the first concrete proposals from pharmaceutical companies to NICE, NHS England and NHS Improvement,” says Professor Geretti.

Can pharma incentives tackle antibiotic resistance?

Understandably, some people might feel queasy about the taxpayer creating incentives for big pharma. But is it so crazy that it just might work?

“It’s the only initiative that any government anywhere in the world has come up with since the AMR review. So let’s give it a chance,” says Lord O’Neill.

But even if the UK scheme does turn out to be an important step in tackling antimicrobial resistance, to address global market failure of new antibiotics, other healthcare systems all over the world will need to follow its lead.

Another dilemma is whether the value NICE and the NHS place on a new antibiotic will be something that is truly attractive to pharmaceutical companies, while remaining economical for the health service.

According to Rebecca Glover and colleagues from the Antimicrobial Resistance Centre at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the model could create “perverse incentives in the future, with companies holding back innovations in the hope that perceived value will increase as antimicrobial resistance rates get worse”.

Lord O’Neill believes we won’t see a significant shift on antimicrobial resistance until pharmaceutical companies show a firm commitment to putting public health before profit. “Less talk, more action,” is needed, he says.

“The amount of talk about the role of pharmaceutical companies and new drugs that has gone on for the past four years is ridiculous relative to the action. I would like the pharmaceutical industry’s leaders to show their Tesla moments,” Lord O’Neill concludes.

Why aren’t new antibiotics being developed?