Although each patient group is small, about 6 per cent of the population will be affected by a rare disease at some point in their life, which in the UK equates to about four million people. To put that into context, there are 1.5 million people with a learning disability. What’s more, rare diseases are becoming less rare as around five new types are described in medical literature each week.

The prevalence of rare diseases is an important principle to establish. For years, policy around the allocation of resources for the treatment of rare diseases has been influenced by the perception that few people are affected and there are more urgent priorities.

As a consequence, access to treatment for a patient with a rare disease historically has been poor. Pharmaceutical companies have focused on blockbuster drugs aimed at treating millions of people and public health systems have been designed to support large population groups. Despite advances in drug development, many rare diseases lack any treatment options.

Stage set for change

There has been a surge in investment in so-called orphan drugs, which are targeted at rare diseases, bringing hope to millions of patients and their families. Last year the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) received a record 582 requests for orphan drug designation from biopharma companies, 110 more than 2015 which was itself a record year. Emerging science is giving drugmakers the tools they need to develop new drugs for conditions that were previously too complex to treat.

Breakthroughs are being made at a time when blockbuster drugs are coming off patent, forcing pharmaceutical companies to explore new revenue streams. Evaluate Pharma, the life sciences intelligence firm, estimates that orphan sales hit $114 billion in 2016, a 12 per cent increase over 2015. The market is set to double over the next six years, accounting for one fifth of the total prescription drug market by 2022, according to some forecasts.

Historically, orphan drug development was mostly performed by small biotechs, but more than half are now created by mid to large pharmaceutical firms. In 2016, the ten best-selling drugs for rare diseases were made by companies including Celgene, Roche, Teva, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Biogen, AbbVie, Amgen and Novartis.

Coping with demand

However, the advent of a new generation of drugs and treatments for patients who previously had no hope creates new challenges for healthcare providers. While systems are being repurposed to speed up access to innovative drugs, the high cost of new medicines remains a formidable barrier.

In England the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) takes decisions based on cost effectiveness, including the impact on quality-adjusted life years. This approach has resulted in a number of promising drugs being rejected, despite their proven effectiveness.

A case is point is Alexion’s Kanuma to treat the rare inherited genetic disorder lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D). Infants with LAL-D normally do not live to see their first birthday without treatment. In clinical trials with Kanuma, five out of nine infants survived beyond three years of age, achieving normal developmental milestones. Yet earlier this year, NICE decided the high cost of the drug, at around £500,000 a patient, could not be justified by its long-term treatment benefits.

Breakthroughs are being made at a time when blockbuster drugs are coming off patent, forcing pharmaceutical companies to explore new revenue streams

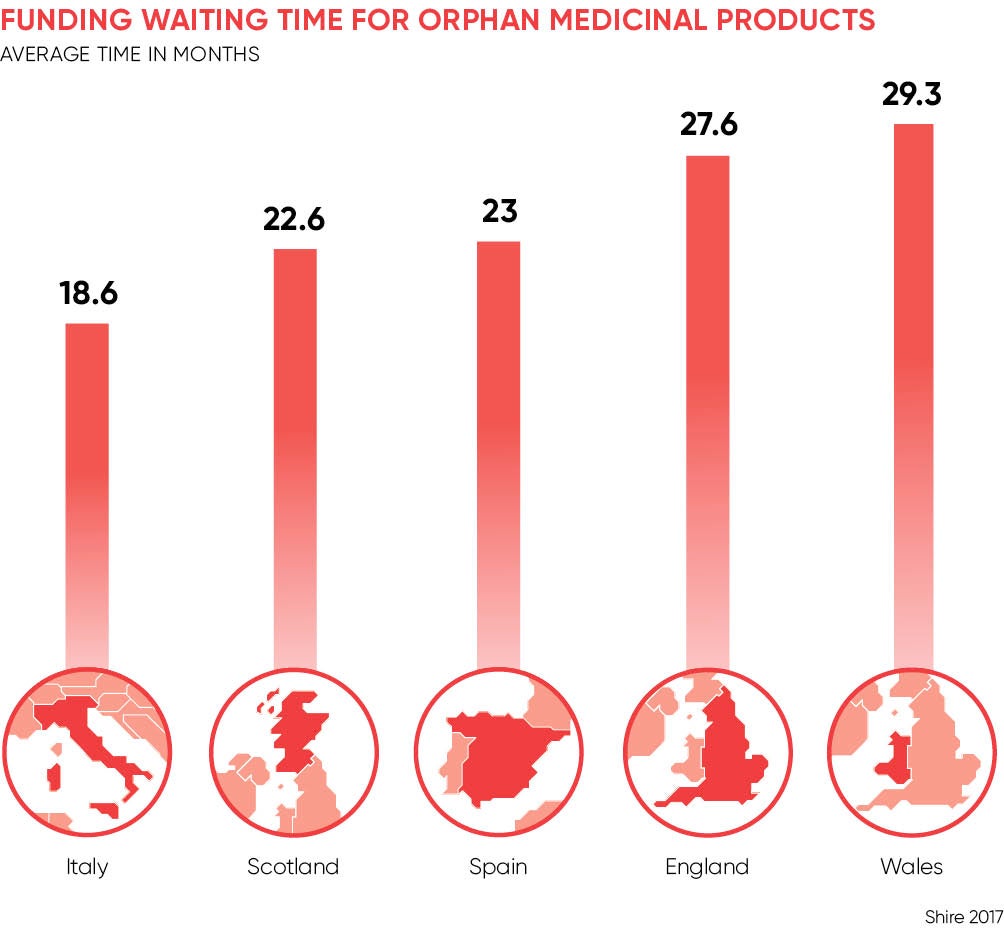

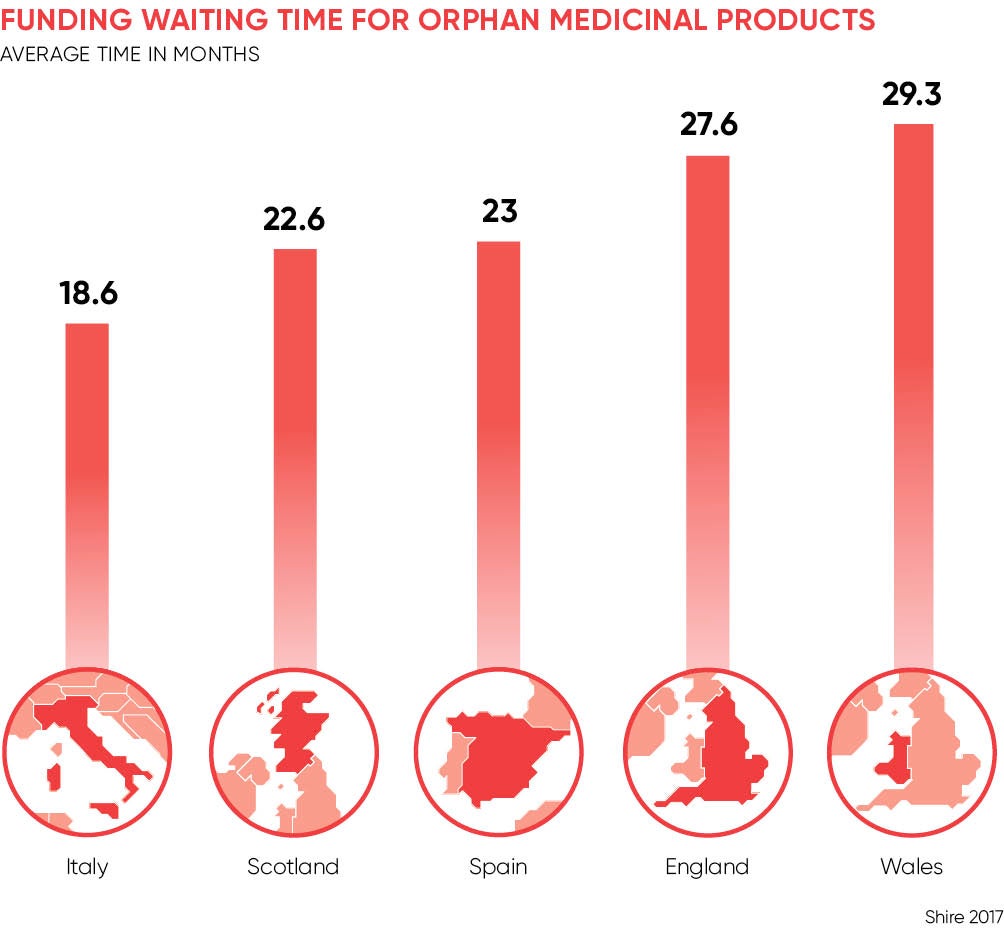

A recent report by Shire Pharmaceuticals, the biotechnology company, revealed that patients with rare diseases in England must wait an average of 28 months for their treatments to be funded by the NHS, longer than in Germany, Italy, France, Spain and Scotland. The report also found that 52 per cent of medicines for rare diseases approved in the last 15 years in England are not funded for routine use. By comparison, Germany funds all orphan medicinal products as soon as they are approved by the European Medicines Agency.

Sebastian Stachowiak, general manager of Shire UK, says: “Patients living with a rare disease in the UK face significant barriers to access life-saving medicines. The UK lags behind European counterparts in speed and access to rare-disease medicines with an assessment process that is not fit for purpose.

“With a general election, the new government has an opportunity to take a bold step to make sure that no patient living with a rare disease is left behind. Industry, government, patient groups and wider stakeholders need to come together to build a bespoke, fit-for-purpose process for evaluating medicines for rare diseases that enables access to treatments for patients living with a life-threatening condition.”

The pharma sector says development costs are the same for orphan medicines as they are for blockbuster drugs, but the cost per patient is exponentially higher. Health providers say developers are abusing the system and must be more open about the true cost of innovation.

This tension has encouraged new research into approved drugs, which may be used to treat another illness and carries less risk than starting from scratch, since the drug has already met regulatory requirements and undergone post-market monitoring.

Elsevier’s R&D Solutions is working with the charity Findacure to tackle rare diseases such as congenital hyperinsulinism and Friedrich’s Ataxia. Tim Hoctor, vice-president of professional services at R&D Solutions, says: “With these kinds of collaborations, the healthcare system saves money, and patients get access to effective and affordable drugs sooner.”

Stage set for change