A kit arrives through the letterbox; it contains materials for collecting saliva and blood samples. You swab your cheeks and prick your fingertips, and send your DNA back to the address given. Within four to six weeks you receive a personalised nutrition report detailing how your body responds to all types of food. You’re then sent weekly recipe suggestions that are tailored to your ideal ratio of fat, carbohydrates and protein.

Data collected through DNA testing and personalising diets is going to have a significant financial impact for food manufacturers as it opens up whole new marketing and revenue opportunities

Welcome to the world of personalisation, an emerging trend in the food industry that is tapping into the health-conscious market. According to the 2016 Nielsen Global Health and Ingredient Sentiment Survey, 70 per cent of 30,000 respondents from across 63 countries said they actively make dietary choices to help prevent health conditions, such as obesity, diabetes and high cholesterol.

The major companies buying into personalised nutrition

Campbell Soup Company and Nestlé are the two biggest names to have taken a gamble on DNA-specific food. In 2016, the former invested $32 million (£25 million) in Habit, the leading DNA-cum-nutrition testing service. Meanwhile, the Swiss food and beverage company is reported to be piloting personalised nutrition in Japan; around 90,000 users of the Nestlé Wellness Ambassador programme can submit photos of their food via an app, which then recommends lifestyle changes. The programme can cost $600 (£468) a year if users want a DNA testing kit and to receive in return specific supplements, such as nutrient-boosted green tea, based on their individual data.

Personalisation is nothing new – it’s long been possible to add a name and message to a cake, decorative biscuit or packaging – but the increase in the number of people, who want to understand the bacteria in their gut, for example, is creating an opening for the industry.

“Data collected through DNA testing and personalising diets is going to have a significant financial impact for food manufacturers as it opens up whole new marketing and revenue opportunities,” says Tarryn Gorre, co-founder of Kafoodle, a food tech startup that combines personalised meal planning with software for monitoring nutritional needs.

“Nutritionally focused food and drink will become more mainstream, but I believe it will be a pull [rather than pushed on consumers]. It will be tailored to those already looking to add a particular nutrient to their diet and even those with allergies,“ Ms Gorre adds.

What will personalised nutrition actually mean for the food industry?

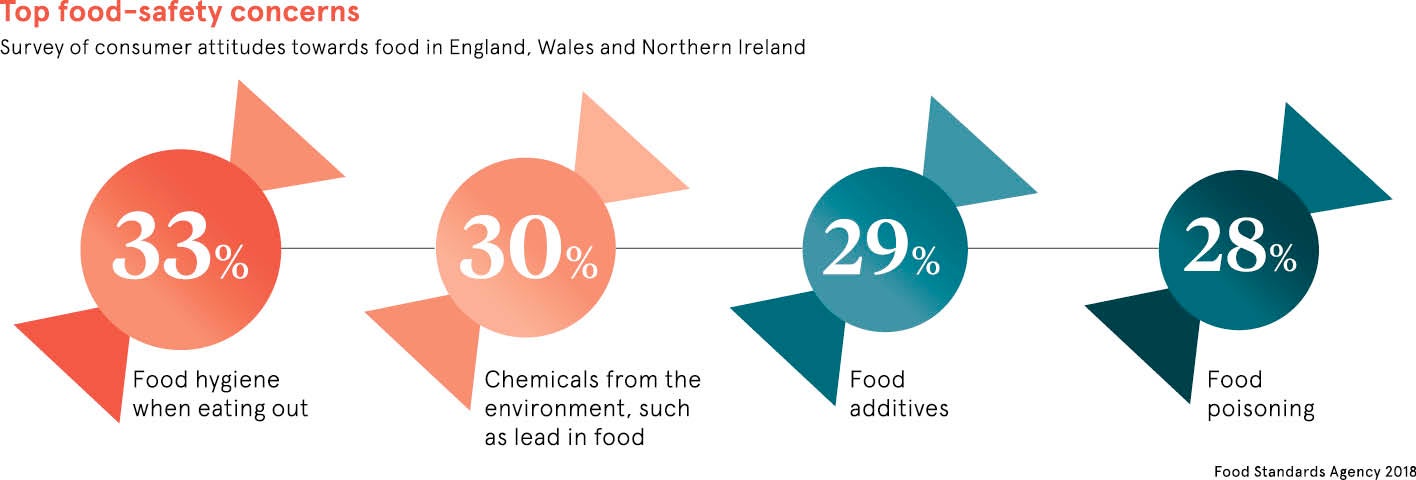

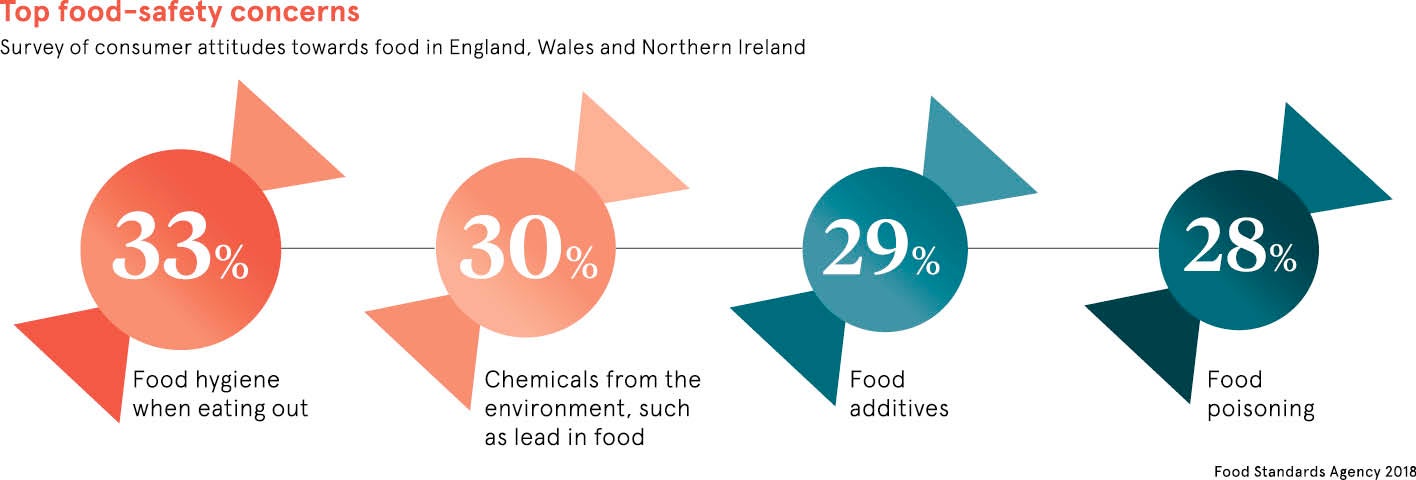

Looking at what this actually means for the food industry, delivering personalised products to the masses won’t be without its challenges. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) in the UK and the US Food and Drug Administration have strict guidelines about what can be put on labels, and the nutritional claims that can and can’t be made.

Ms Gorre says there’s also the concern that it could increase food waste. Products would have to be processed and manufactured in advance, but by the time they reach consumers, there may no longer be the demand for them.

Dr Shaobo Zhou, senior lecturer in nutritional science at the University of Bedfordshire, believes scientific, legal, social and economic barriers mean you’re not likely to see the major food manufacturers developing personalised products to be sold by supermarkets, at least not for now.

“Given the unanswered questions around personalising nutrition, it’s unlikely you’ll see a food company produce individualised products on an industrial scale,” says Dr Zhou. “Focusing on more pressing issues, like reducing salt and sugar levels, would be a much more impactful way for the food industry to improve individual and public health.”

While personalised nutrition products may not be sitting on shop shelves in the near future, what is likely to happen is that food companies will partner with startups and tech companies to improve existing processes and services, in catering and hospitality settings, for example.

“I think personalised eating is an experience that will be integrated into many dining establishments. There will be a rise in a more component way of eating. For instance, salads bars will use food technology to enable consumers to tailor each salad to their exact preference, by adding protein or reducing carbohydrates,” argues Ms Gorre, whose own company has developed software to optimise the nutritional care of patients and residents in the health and social care sectors.

Personalised nutrition requires customer engagement and trust to succeed

At the other end of the spectrum, small brands without the resources to invest in DNA-cum-nutrition testing, will play a role in personalising food delivered to the door. One such brand is Allplants, a startup that delivers plant-based meals prepared by experienced chefs.

Allplant’s co-founder Alex Petrides, who founded the startup with his brother Jonathan, believes smaller companies can be better at getting to know consumers on a personal level and understanding their preferences.

“We’ve been visiting our customers in their homes from day one. It helps us to understand the role we’re playing in their lives, what we’re doing right, by luck or design, and friction points that we can improve on,” says Mr Petrides, former brand director at Propercorn, marketed as a healthy snack.

“Sometimes it simply helps us to realise things, like the fact that people are taking our meals to work for lunch. Then we can tailor our offering further, by selling personalised cooler bags, for example. [Engaging with customers] is constant market research, and it’s critical to our continual improvement and building the trust behind our brand.”

In the FSA’s latest Biannual Public Attitudes Tracker, 75 per cent of those surveyed said they trust that food is what it says it is and that it’s accurately labelled.

As the trend of personalising diets continues to grow, finding ways to build trust will be essential, especially if you’ll be handing over your DNA for the ideal amount of protein in your diet.

The major companies buying into personalised nutrition

What will personalised nutrition actually mean for the food industry?