Despite the gloomy economic news coming out of India, the pharmaceutical sector still looks solid. Drill down and you realise why: the country is the largest provider of generic drugs globally and accounts for 60 per cent of all vaccines produced worldwide. It is a heavyweight in industry circles and the planet’s third-largest producer of drugs by volume. These are astounding numbers.

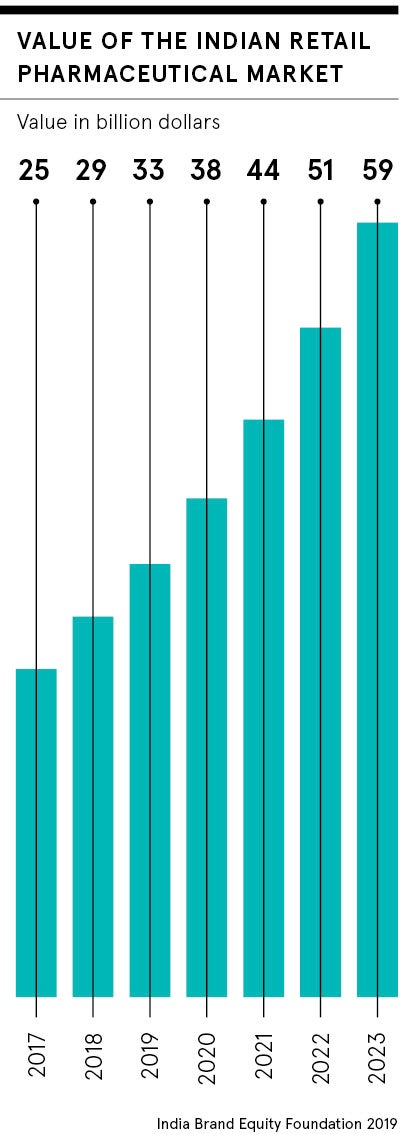

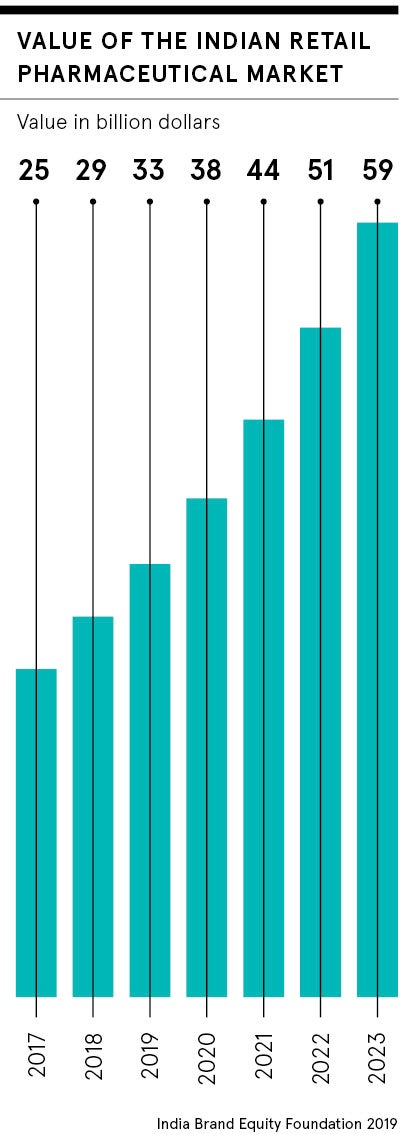

While the country’s economic growth sinks under 5 per cent, the Indian pharmaceutical industry is growing by 7 to 8 per cent a year, according to the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, while rating agency ICRA expects growth of 11 to 13 per cent in 2020. Strong demand is buoyed by better access to medicines in the domestic market, increasing spending on healthcare, and a higher incidence of chronic diseases.

“This is supported by a rising middle class whose disposable income keeps growing rapidly; a large proportion of these funds is being spent on healthcare and health insurance as the country and its people develop and mature,” explains Vikas Bhadoria, senior partner at McKinsey & Company.

“Currently, Indian consumers are spending nearly 1 per cent of their total income on drugs and pharmaceuticals. With the rise in the per capita income, current spending is going to triple, to approximately $33 per annum, by 2020.”

The market is already worth $38 billion a year, which includes exports. It employs 2.7 million people directly or indirectly and has world-class capabilities in formulation development. There’s a strong entrepreneurial spirit in the Indian pharmaceutical industry with an established footprint in large international markets such as the United States. The industry is now India’s fourth-largest exporter of goods.

“The country’s growing capabilities in contract manufacturing, research and development, as well as clinical trials, also make it a preferred partner for the global pharmaceutical industry,” says Sujay Shetty, health industries leader for India and partner at PwC.

Buoyed by world’s biggest health scheme

Then there’s the Ayushman Bharat Yojana, launched only last year. This government healthcare programme is the biggest in the world and is aimed at providing affordable treatment for 500 million people, or 40 per cent of India’s population, including 100 million vulnerable families.

“This is seen as an opportunity by pharma companies to help the underserved masses with affordable drugs,” notes Tim Hoctor, vice president of professional services at Elsevier.

Still there are many challenges. Healthcare infrastructure in India is inadequate when compared to the size of its population. Roughly 29 skilled health workers are available for every 10,000 people in India compared with 41 in China and 111 in the United States. Fewer than a third of Indians have health insurance, the rest deal with medical bills directly.

“The inability to pay for medicines is another challenge that many people face. The Indian government’s expenditure on healthcare is low, about 1 per cent of GDP compared to 2.5 to 3 per cent of GDP when analysing other developing economies such as China, Malaysia and Thailand,” says McKinsey’s Mr Bhadoria.

Despite the potential for growth in the Indian pharmaceutical industry, it is being squeezed from many sides. Generic drugs manufacturers are facing stringent pricing pressures from the government that is keen to make treatment more affordable, yet Indian medicines are already the lowest priced in the world. At the same time, growth in its key US export market is moderating, due to price erosion and greater scrutiny from regulators.

“Generics exports, specifically to the United States, have been a key driver of double-digit growth for top Indian pharmaceutical companies over the last few years. America accounts for over a third of total exports. Indian drugs reduce healthcare spend in the United States to the tune of over $20 billion every year,” says Mr Bhadoria.

“Despite investments by some companies in newer product classes, such as biosimilars and specialty drugs, the contribution of non-generic products to the current revenue of pharma companies is miniscule.”

Indian pharmaceutical industry slow to innovate

The Indian pharmaceutical industry has been slow to innovate when it comes to new molecules or complex generic drugs. There’s also a limited government-supported research ecosystem. Certainly, there is scope to improve collaboration between state-run institutes and industry.

“A talent pool with advanced skills is also limited in India, with only 2,000 PhD students enrolled in pharmacy institutes, compared to over 15,000 PhD students enrolled in the United States,” Mr Bhadoria explains.

As the disease burden in India transitions towards chronic diseases, there is rising demand for specialised medicines, which are currently more expensive than acute drugs. What India’s pharmaceutical industry is extremely good at though is producing quality medicines at keen prices, especially when they fall off the so-called patent cliff. Therein lie future opportunities.

“India today is the primary supplier of essential medications for numerous disease areas worldwide, helping save millions of lives every year. If it extends this noteworthy cause of affordable, accessible medicine to the world, it could be a winner,” Mr Bhadoria concludes.

Buoyed by world’s biggest health scheme