Community pharmacies are critical to the delivery of healthcare. More than 1.6 million people visit a pharmacy every day and the NHS spends £17.4 billion a year on medicines, more than half of which is in primary care.

Given this important role, you might expect pharmacies to be highly connected to the rest of the health service, sharing patient information and data with GPs, doctors and nurses.

Digitising the prescribing and distribution of medicines has an enormous potential to improve patient care, increase safety and make our system in the NHS more efficient

The reality is very different. Pharmacy is fragmented, made up of thousands of owner-managed businesses and operating independently of health centres and hospitals. Community pharmacies were early adopters of new technology in the 1980s, but little has changed since. Pharmacists spend much of their time performing tasks that could easily be automated.

Reliance on paper-based processes gets in the way of connectivity with other parts of the NHS, which causes a huge administrative burden. It not only costs money, but it also increases the risk of errors. Up to half of patients don’t take their medicine as intended and one of the reasons is that pharmacists don’t have the time or resources to support patients as they would like.

New legislation to tackle fake medicines

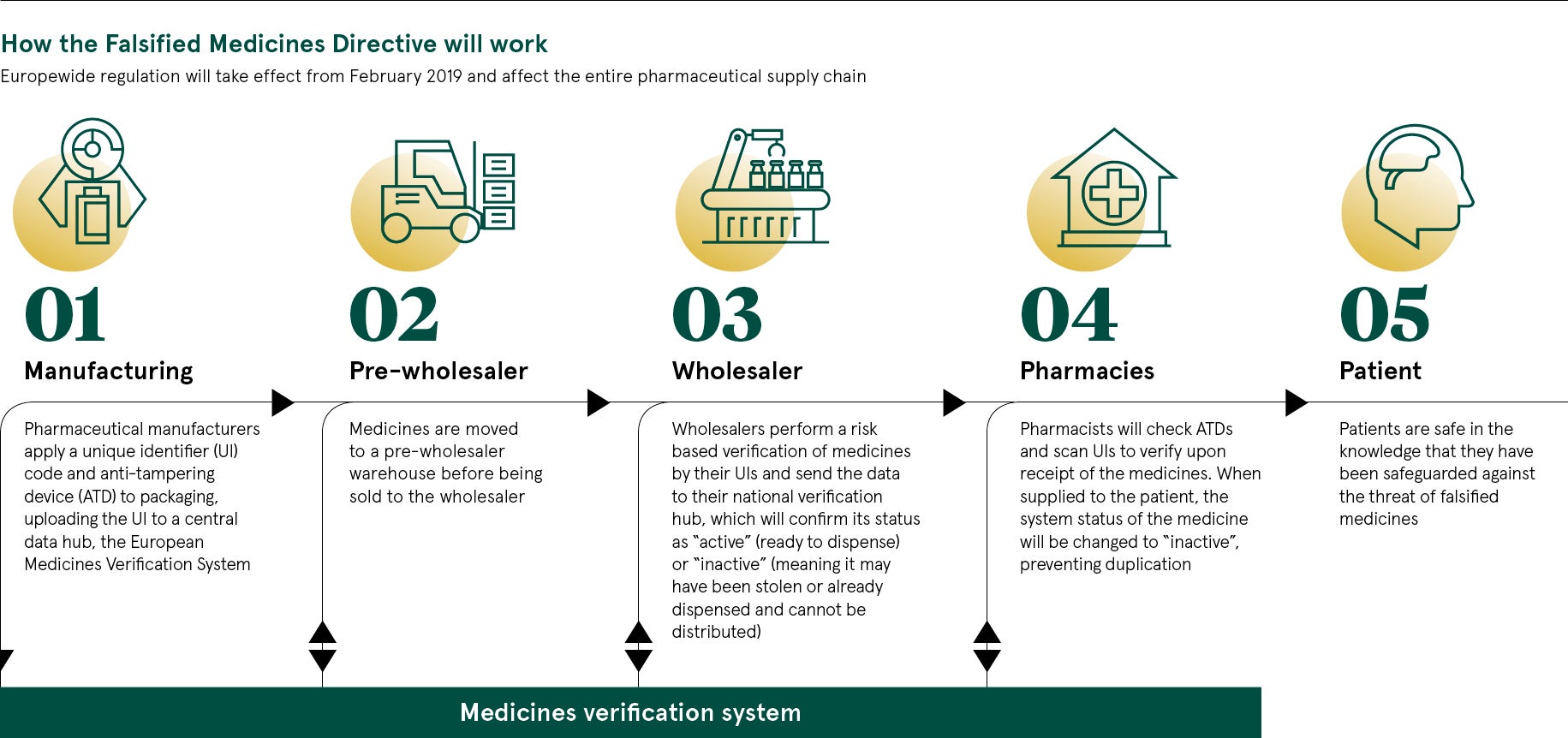

Digitising the prescribing and distribution of medicines has an enormous potential to improve patient care, increase safety and make the NHS more efficient. There are hopes that a catalyst for change could be the implementation of a scheme introduced across the European Union aimed at eradicating fake medicines.

The scheme, known as the Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD), comes into effect on February 9, 2019. From this date, UK pharmacies will be expected to scan medicines before they are dispensed, using a unique identifier in the form of a barcode. This will be registered on a database called the European Medicines Verification System.

Compliance with FMD requires community pharmacies to adopt new software and cloud-based repositories of data. This could be the ideal moment to consider further opportunities afforded by new technology. NHS England, through its Digital Medicines programme, is encouraging pharmacies to harness the power of technology, so there is significant support across the health service.

However, progress has been held up by uncertainties over the future of FMD, which cast a shadow over plans for broader technological innovation in pharmacies. Brexit is a significant issue, which makes it unclear whether UK pharmacies must comply with the EU directive that drives FMD.

Pharmacy concerns around addressing fake medicines

Many other questions remain, including which scanners can be used and who will bear the cost. This is a particularly pertinent issue at a time of tough financial settlements with the Department of Health and Social Care. And many pharmacists question whether the problem of fake medicine is actually big enough to justify this major investment programme.

With the clock ticking down, many of the systems and pieces of equipment required to implement the policy are still being designed. This makes it difficult to assess how much FMD will cost pharmacists. Estimates vary between £522 million and £813 million, which includes training.

Aileen Bryson, practice and policy lead for the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, says: “The FMD is a way of working between countries. It is intended to improve the patency of the supply chain from manufacturing right through to patients.” If the UK did not adopt this way of working and counterfeiting was to increase in future, “the UK would be the weak link in the chain”, she says.

There are concerns around how the outcome of the Brexit negotiations will affect the UK system linking with Europe. Despite this, pharmacies recognise the system is required for patient safety and are working to meet the deadline for FMD.

But Ms Bryson hopes the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, or MHRA, would take a proportionate approach to penalties as indicated in recent consultation, reserving criminal sanctions for wilful disregard for the new legislation.

Will the Falsified Medicines Directive hold pharmacies back?

Given all this uncertainty, FMD is becoming something of a drag on investment by community pharmacists, rather than a catalyst for change. This is a concern for NHS Digital, the NHS body responsible for information and technology across health and social care.

Vishen Ramkisson, senior clinical lead at NHS Digital, says: “Digitising the prescribing and distribution of medicines has an enormous potential to improve patient care, increase safety and make our system in the NHS more efficient. We have made great progress, but there remains a reliance on inefficient, paper-based processes, which slow us down, increase the potential for errors and cost money.”

Integrating community pharmacy into the wider health service is a priority for NHS Digital. The ambition is to give pharmacists and their teams access to relevant clinical information, enabling them to communicate more easily with patients and other health professionals.

NHS Digital also wants community pharmacists to be able to contribute to patient records, so pharmacists, doctors, nurses and other health professionals will have more up-to-date information about their patients.

At the same time, it should be possible for NHS 111, GPs and hospitals to refer patients directly to community pharmacies, which will relieve the pressures on GPs, speed up hospital discharge and ensure patients have the support they need at home.

Under new regulation, pharmacy staff will have to check anti-tampering devices, scan and verify all medicines before supplying to patients

Electronic prescribing could combat fake medicines

A critical element is the extension of electronic prescribing, or EPS. Instead of a paper prescription, patients have a token with a unique barcode which can be scanned at any pharmacy to retrieve the medication details.

At the moment, electronic prescriptions account for around 40 per cent of all prescriptions issued in England. Steps are being taken towards making electronic prescribing the default option for prescribing, dispensing and reimbursement of prescriptions in primary care. The latest phase of EPS will increase the proportion of prescriptions sent electronically to around 90 per cent.

Technology also offers possibilities to reduce labour-intensive work, freeing up more time for pharmacists to spend with patients. In Scotland, pharmacies have been able to invest in dispensing robots with the help of the Scottish government. Financial grants were offered to support investment in robotics and scanners as part of its Prescription for Excellence strategy for the sector. Scotland also has its first 24-hour automated prescription collection point.

New legislation to tackle fake medicines