It is often said that the state of our skin provides a litmus test for our overall health, so why do so few of us understand what a qualified dermatologist is?

As a discipline, dermatology is concerned with far more than the cosmetic; skin diseases can be serious. But according to Dr Angelika Razzaque, executive chair of the Primary Care Dermatology Society (PCDS), even doctors need to clue up on the subject.

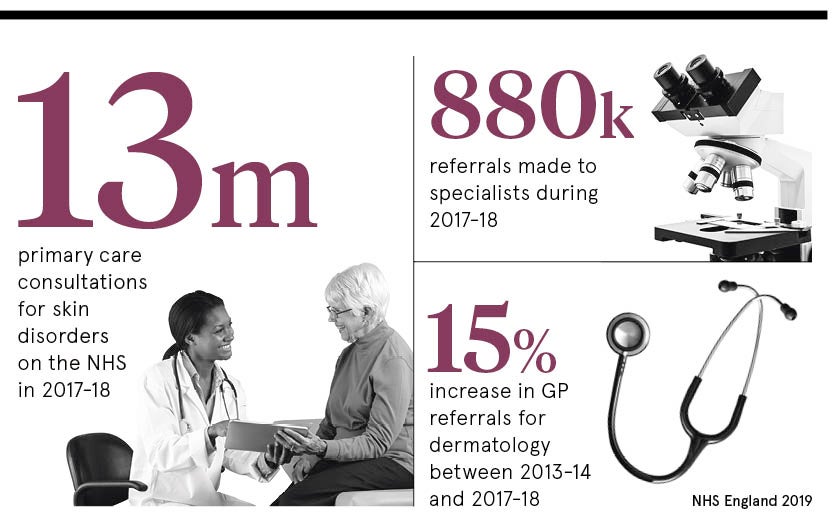

“Most medical schools offer only up to two weeks dermatology education,” she says. “Clinics are overburdened with a two-week wait for skin cancer referrals, yet the majority seen are not cancer. GPs and primary care clinicians don’t feel suitably equipped to manage skin conditions, including lesions, in the community.”

The expectations and responsibilities of a qualified dermatologist are manifold, yet rarely explored. “It’s almost artificial to divide the medical and cosmetic,” says Dr Paul Charlson, president of the British College of Aesthetic Medicine. “People come with their skin problems – lumps and marks – and you give them a whole range of ideas because people are quite ignorant as to what they can do for their skin. So, often I might be doing some aesthetic work and find they have skin cancer. That happens not infrequently.”

Cosmetic procedures vs. skin diseases

This is when the question “what is a dermatologist?” becomes urgent to the point of potentially life-saving. “I saw a patient the other day who was treated at a skin clinic with a CryoPen for something that he had on his head which was clearly a basal cell carcinoma,” Dr Charlson recalls. The patient had gone to a high street clinic which can’t have examined the lesion with a dermatoscope. “It’s potentially a risky thing with a melanoma: ‘Oh, it’s just a brown mark. I’ll treat it with a freezing instrument or a cream and it’s a potentially lethal cancer,” he says.

The same thing goes for a “funny” rash that turns out to be dermatomyositis or lupus. Dr Charlson adds: “Among all the common stuff, there’s the rare and dangerous, so I think not having the ability to make the diagnosis and treating it is potentially a problem.”

While it may be quick and convenient to nip into a high street clinic to talk about your skin problems, your first port of call over any skin worry, the professionals insist, is your GP who should be able to refer you to a qualified dermatologist if there is real cause for concern.

The PCDS is currently working hard to provide medical training for GPs in the diagnosis and treatment of the most often seen conditions such as eczema, psoriasis, acne, itchy skin, lesions, infections, hair and nails, urticaria and other inflammatory conditions. There’s also an emphasis on dermoscopy training as many GPs want to learn how to use additional tools aiding them in making a diagnosis.

Qualified dermatologist ensures patient safety

In this context, Dr Razzaque insists: “Patient safety is paramount in all our dealings. Most important is that clinicians have enough time to communicate with patients and involve them in decision-making. Closer working between primary and secondary care would be highly beneficial to patients and increase safety and satisfaction.”

Considering the need for them, the lack of qualified dermatologists in the NHS isn’t just puzzling, it’s seriously concerning, according to Dr Adam Friedmann, consultant dermatologist at The Dermatology Partnership and formerly dermatology teaching lead for University College London medical students.

“There are fewer than 1,500 consultant dermatologists in the UK, many of whom do not do any cosmetic work,” he explains. “I would guess there are probably in excess of 10,000 cosmetic practices in the UK, which gives an idea as to how many practitioners there are out there who are not dermatology consultants.”

Combating the dermatology skills gap

The “enormous” skills gap in primary and secondary caregivers needs to be addressed, says Dr Friedmann, adding: “Expertise in dermatology is an extreme rarity. To become a consultant dermatologist usually takes seven to ten years of training exclusively in dermatology. By comparison, general practitioners receive little training in dermatology. For example, in medical school, sometimes as little as only a single week is set aside for teaching dermatology over a five-year course. Given that 15 to 20 per cent of the GPs workload comprises skin disease, this is clearly disproportionate.”

Bridging the public information gap

Another challenge, in addition to the skills gap, is the public information gap as people generally know even less. Dr Friedmann points to public information campaigns by the British Association of Dermatologists and the British Skin Foundation as helpful, but more needs to be done. “Education on the basics of what to look out for in terms of changing moles or skin cancer tends to be useful as does advice on appropriate sun avoidance,” he says.

Demand for cosmetic procedures, such as Botox and lip-fillers, have “absolutely ballooned” in demand over recent years, says Dr Charlson. “Unfortunately, this has led to the creation of a community of the ‘unconsciously incompetent’ who go on courses and think they know what they’re doing,” he says.

A career in dermatology

Dermatology, as the experts are keen to state, is an attractive medical discipline to go into because there is no night-working, which makes it family friendly. So why are there still so few qualified dermatologists?

Dr Charlson thinks this might be rooted in our attitudes to skin complaints. We view them as an aesthetic matter rather than something serious. “Changes of attitudes to conditions like acne are quite important,” he concludes. “There’s a lot of psychological trauma involved, particularly with the selfie generation.”

Ultimately, whether tackling teenage spots or correctly identifying a cancerous mole, it’s clear that “what is a dermatologist?” is a question we should all know the answer to.

Cosmetic procedures vs. skin diseases

Qualified dermatologist ensures patient safety

Combating the dermatology skills gap