In an era of extreme healthcare crisis, there is one added threat that can’t be repelled with personal protective equipment, a vaccine or social distancing. While frontline medics battle the present threat of coronavirus, many hospitals have been paralysed by a new plague. This summer, ransomware attacks have been shutting down hospitals in their time of need.

A single attack paralysed Dusseldorf University Hospital, which meant ambulances loaded with emergency patients were re-routed to other emergency centres. A female patient died on the way to another unit. Elsewhere a network of 400 health centres with university health services were shut down by Ryuk ransomware, denying staff access to radiology studies, lab reports and cardiograms.

NHS Digital blocks more than 21 million items of malicious activity every month. This didn’t stop a Wannacry outbreak in 2017 which cost £92 million and left doctors and nurses using pen and paper to send notes and phone texts.

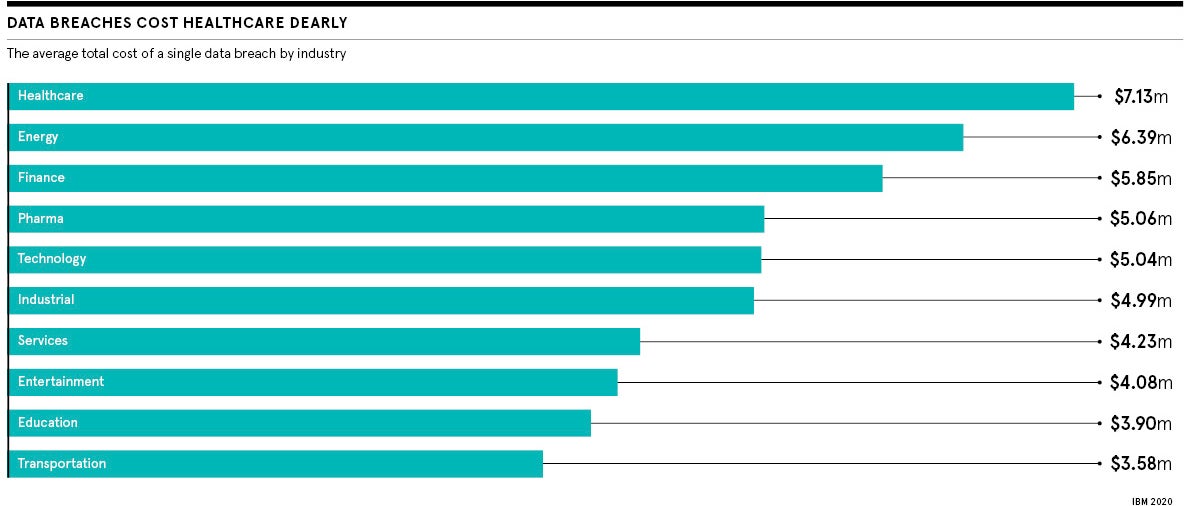

According to a recent IBM security report, healthcare companies suffered the largest breaches in each of the past six years and so far this year 52 per cent were malicious attacks. Around 13 per cent are believed to be the work of hostile governments, with rival states knowing the best way to undermine another is to crash their healthcare. Ransomware is a political issue as well as a matter of security.

Understanding why ransomware works

While mass vaccination may be on the horizon for COVID-19, there is no such silver bullet for ransomware. It does not infect by contact, moving from one IP address to the next. It is much smarter. Inside a system, ransomware actively seeks out high-security privileged passwords or logins so it can wreak much more havoc.

Ransomware never sleeps and is human behaviour-specific, says Theresa Lanowitz of AT&T Cybersecurity, who trains employee networks to understand threats.

“Hackers already know, over a long holiday weekend, a large organisation doesn’t have people staffed 24/7 and they target that path of least resistance. Therefore, COVID and remote working present unique opportunities for ransomware,” she says.

Ransomware hackers target hospitals because they typically have a mix of ageing and new technology, a huge workforce of varied privileges and, most importantly, they often have no choice but to pay and pay fast.

Also, the caring nature of healthcare staff lends itself to having kindness used against them. Post-lockdown, emails containing ransomware, either claiming to be raising cash for victims or to come from healthcare directors or trustworthy organisations, such as the World Health Organization, plague healthcare. They have plausible subject lines to increase the chance of being opened and acted upon.

Why hackers ask for small ransoms

Remote working increases cross-contamination, with staff relying on personal devices. An Android app claimed to provide a map that provided real-time virus-tracking. In reality, the app delivered ransomware onto victims’ phones and demanded a ransom to return access. Others, such as Trickbot, install on machines via a spam targeting email to not only steal confidential information, but also assist in installing other forms of malware, increasing the scale of the attack.

They are asking for $10,000 because they know you will pay that. And they’ll come back for another ransom next month and the one after

There’s also the threat of double extortion. Ransomware actors know if hospitals don’t pay, they face a much larger data breach fine from their regulators, says Tom Lysemose Hansen of security analysts Promon. “TA2101, the aggressive group behind the Maze ransomware, have even gone as far as creating a dedicated web page which lists the identities of their victims and regularly publishes samples of stolen data,” he says.

Of victims who pay the ransoms to restore capability, only 19 per cent ever get their data back, according to a report from the CyberEdge Group.

In the case of the attack on Baltimore, threat actors asked for $15 million to recalibrate the city, but many are reducing ransoms to ensure a quick payout from hospitals. “They are asking for $10,000 because they know you will pay that,” says Daniel Conrad of One Identity, who advise on privileged access management and employee security training. “But, the thing is, they stay within your network once you’ve paid. And they’ll come back for another ransom next month and the one after. Pay it and you are not solving the problem.”

How do you prevent ransomware?

Before confronting the enemy at the gates, focus on ensuring your staff don’t leave the drawbridge down. Promon’s survey of 2,000 remote workers found 66 per cent haven’t been given any form of cybersecurity training in the past 12 months, with a further 77 per cent saying they aren’t worried about their cybersecurity while working from home.

Staff can no longer leave their workstation unlocked, fail to challenge things they don’t recognise or practise bad password management. Executives need to lead from the front in creating good cyber-hygiene and not rely on a single IT department, says Conrad. “Just as staff wouldn’t dream of coming onto a ward with a cough during coronavirus, health staff should be obsessed about not being the one who infects the entire network with a ransomware or phishing attack.”

Unfortunately, many training firms and advisers are only brought in after a breach, says Javvad Malik, client trainer at KnowBe4 security employee training. One client had a brand-new site hacked and data stolen. Upon investigation, it was found that, as security testing often took a number of days to clear a new site, marketing had not conducted any security testing before launching, as they didn’t want to wait. After all, they’d never had a breach before.

Apathy leaves units wide open. Hospitals are a huge internet of things (IoT) growth area, yet many get new devices and keep the default password, says Lanowitz of AT&T Cybersecurity. “All a hacker has to do is get the original default password from the manufacturer and they are then into that IoT device and can move laterally across your network shutting everything down.”

A centre is only as strong as its weakest link. Where possible, with staff working remotely, be clear to remove responsibility where possible. “Don’t give users the ability to install their own software; manage it centrally, even in lockdown,” says Conrad. “I’ve seen instances where, working remotely, an employee has gone on the internet to get software they need for their job and then download something corrupt or with Trojan horses built in.”

Defeating ransomware is about sharing information

Like defending any structure, employ reconnaissance to see threats coming and to help you understand the risk to your organisation.

Securonix director Jon Garside was the notification officer for Obamacare in California from 2014-15, a responsibility which covered 60 million personal records. He insists any major organisation should subscribe to multiple threat intelligence feeds and share the information they provide with staff. “I would advise to use Gigamon or Opora; Opora shares not just attack vectors, but adversary techniques,” says Garside.

AT&T Cybersecurity offers European and US teams, who are part of the Open Threat Exchange, a forum of 145,000 security professionals who identify suspicious URLs, emails and threats, and seek to understand how they might behave. Ransomware, almost like a virus, readily mutates and has to be tracked.

“You don’t just tell your unit, you tell the world,” says Lanowitz. “Information is vital: to say this threat is moving across the Atlantic into Europe. Protect your digital assets by knowing a threat is coming.”

Keep surgical levels of hygiene and insist anything that comes into contact with a network, whether it is a desktop computer, laptop, medical equipment, applications or even a patient’s wearable device, must be protected. If you don’t, it is not a case of if, but when a hacker will be holding your organisation to ransom.

In an era of extreme healthcare crisis, there is one added threat that can’t be repelled with personal protective equipment, a vaccine or social distancing. While frontline medics battle the present threat of coronavirus, many hospitals have been paralysed by a new plague. This summer, ransomware attacks have been shutting down hospitals in their time of need.

A single attack paralysed Dusseldorf University Hospital, which meant ambulances loaded with emergency patients were re-routed to other emergency centres. A female patient died on the way to another unit. Elsewhere a network of 400 health centres with university health services were shut down by Ryuk ransomware, denying staff access to radiology studies, lab reports and cardiograms.